E Syllable Yi in Old Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Nzila Ye Isa Kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli

NzilaYeIsakwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli Kana Mu I Fumani? ULIMU YA M’ATA OTE ki yena Mubusi wa pupo kamukana. Bupilo bwa luna M bwa cwale ni bwa kwapili bu itingile ku yena. U na ni m’ata a ku fa mupuzonim’ataakufakoto.Unanim’ataakufabupilonim’ataakubu felisa.Haibalutabelwakiyena,likalikalubelahande;haibah’alutabeli,lika ha li na ku lu bela hande. Ki kwa butokwa luli kuli bulapeli bwa luna ibe b’o a amuhela! ˜ Batubalapelakalinzilazenata. Haiba bulapeli bu swana ni nzila, kana Mulimu wa amuhela linzila kaufela za bulapeli? Kutokwa. Jesu, yena mupolofita wa Mulimu, n’a bonisize kuli ku na ni linzila ze peli fela. N’a ize: ˜ “Munyako wa Sinyeho u atami, mi nzila ye ya mwateniiatami,mibabakena ˜ ˜ mwateni ki ba banata. Kakuli munyako wa bupilo wa kumbana, nzila ye ya ˜ mwatenikiyesisani,mikibabanyinyanibabaifumana.”—Mateu7:13,14. ˜ Ku na ni mifuta ye mibeli fela ya bulapeli: bo bunwi bo bu isa kwa ˜ bupilo ni bo bunwibobuisakwasinyeho.Mulelowa broshuwa ye ki ku mi tusa ku fumana nzila ye isa kwa bupilo bo bu sa feli. Mukoloko wa ze Mwahali NzilaYeIsakwa 1 Kana Bulapeli Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli KaufelaBuLutaNiti? ......... 4 2 MuKonakuItuta ˜ Kana Mu I Fumani? CwaniNitikazaMulimu? ..... 5 ˜ 3KiBomani Ba Ba Pila mwaLilukolaMoya? ......... 8 4 Bokukululu ba Luna Ba Kai? . 12 5 NitikazaMabiboniBuloi .... 15 6 Kana Mulimu Wa Amuhela BulapeliKaufela?............ 19 ˜ 7KiBomani Ba Ba Na niBulapelibwaNiti? ........ 22 8 Mu Hane Bulapeli bwa Buhata; Mu Swalisane niBulapelibwaNiti ......... 25 9 Bulapeli bwa Niti Bwa Kona kuMiTusaKuYaKuIle!...... 29 2002 Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania Nzila Ye Isa kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli—Kana Mu I Fumani? Bahasanyi Printed by Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of South Africa NPC 1 Robert Broom Drive East, Rangeview, Krugersdorp, 1739, R.S.A. -

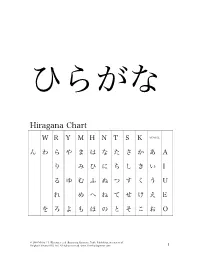

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

History and Narrative in Japanese Chiyuki Kumakura

Document generated on 09/27/2021 10:48 a.m. Surfaces History and Narrative in Japanese Chiyuki Kumakura CULTURE AND INSTITUTIONS Article abstract Volume 5, 1995 This essay analyzes what Oe Kenzaburo (1994 Nobel laureate in literature) calls two opposing poles of ambiguity. The modernization of the Japanese URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065000ar language has been oriented toward learning from and imitating DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065000ar Indo-European languages (or Chinese), which permits one to make objective statements. Yet native Japanese (yamato kotoba) is unequivocally oriented by See table of contents the speaker's standpoint which is naturally subjective, reflecting only his/her perceptions and judgments. To Oe, this ambiguous orientation of the Japanese language has forced its culture into obscurity and isolation. In my analysis, the "interpersonal" nature of Japanese (derived from the speaker orientation) and Publisher(s) the interpersonal culture of Japan (derived from the language) have created a Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal culture that appears ambiguous and may often be considered inscrutable from a European perspective. However, interpersonality as a feature of Japanese culture and in Japanese discourse is a new concept that deserves further ISSN examination. 1188-2492 (print) 1200-5320 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Kumakura, C. (1995). History and Narrative in Japanese. Surfaces, 5. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065000ar Copyright © Chiyuki Kumakura, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit.