The Feferal Security Service of the Russian Federation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

Welfare Reforms in Post-Soviet States: a Comparison

WELFARE REFORMS IN POST-SOVIET STATES: A COMPARISON OF SOCIAL BENEFITS REFORM IN RUSSIA AND KAZAKHSTAN by ELENA MALTSEVA A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Elena Maltseva (2012) Welfare Reforms in Post-Soviet States: A Comparison of Social Benefits Reform in Russia and Kazakhstan Elena Maltseva Doctor of Philosophy Political Science University of Toronto (2012) Abstract: Concerned with the question of why governments display varying degrees of success in implementing social reforms, (judged by their ability to arrive at coherent policy outcomes), my dissertation aims to identify the most important factors responsible for the stagnation of social benefits reform in Russia, as opposed to its successful implementation in Kazakhstan. Given their comparable Soviet political and economic characteristics in the immediate aftermath of Communism’s disintegration, why did the implementation of social benefits reform succeed in Kazakhstan, but largely fail in Russia? I argue that although several political and institutional factors did, to a certain degree, influence the course of social benefits reform in these two countries, their success or failure was ultimately determined by the capacity of key state actors to frame the problem and form an effective policy coalition that could further the reform agenda despite various political and institutional obstacles and socioeconomic challenges. In the case of Kazakhstan, the successful implementation of the social benefits reform was a result of a bold and skillful endeavour by Kazakhstani authorities, who used the existing conditions to justify the reform initiative and achieve the reform’s original objectives. -

The Siloviki in Russian Politics

The Siloviki in Russian Politics Andrei Soldatov and Michael Rochlitz Who holds power and makes political decisions in contemporary Russia? A brief survey of available literature in any well-stocked bookshop in the US or Europe will quickly lead one to the answer: Putin and the “siloviki” (see e.g. LeVine 2009; Soldatov and Borogan 2010; Harding 2011; Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky 2012; Lucas 2012, 2014 or Dawisha 2014). Sila in Russian means force, and the siloviki are the members of Russia’s so called “force ministries”—those state agencies that are authorized to use violence to respond to threats to national security. These armed agents are often portrayed—by journalists and scholars alike—as Russia’s true rulers. A conventional wisdom has emerged about their rise to dominance, which goes roughly as follows. After taking office in 2000, Putin reconsolidated the security services and then gradually placed his former associates from the KGB and FSB in key positions across the country (Petrov 2002; Kryshtanovskaya and White 2003, 2009). Over the years, this group managed to disable almost all competing sources of power and control. United by a common identity, a shared worldview, and a deep personal loyalty to Putin, the siloviki constitute a cohesive corporation, which has entrenched itself at the heart of Russian politics. Accountable to no one but the president himself, they are the driving force behind increasingly authoritarian policies at home (Illarionov 2009; Roxburgh 2013; Kasparov 2015), an aggressive foreign policy (Lucas 2014), and high levels of state predation and corruption (Dawisha 2014). While this interpretation contains elements of truth, we argue that it provides only a partial and sometimes misleading and exaggerated picture of the siloviki’s actual role. -

V. Makarov A. Guseynov A. Grigoryev

ss1-2012:Ss4-2009.qxd 06.02.2012 17:20 Страница 252 E D I T O R I A L C O U N C I L V. MAKAROV A. GUSEYNOV Chairman Editor-in-Chief Academician of RAS Academician of RAS A. GRIGORYEV Deputy Editor-in-Chief M E M B E R S O F T H E C O U N C I L L. ABALKIN, Academician V. STEPIN, Academician A. DEREVYANKO, Academician V. TISHKOV, Academician T. ZASLAVSKAYA, Academician Zh. TOSHCHENKO, Corr. Mem., RAS V. LEKTORSKY, Academician A. DMITRIYEV, Corr. Mem., RAS A. NEKIPELOV, Academician I. BORISOVA, Executive Secretary G. OSIPOV, Academician Managing Editor: Oleg Levin; Production Manager: Len Hoffman SOCIAL SCIENCES (ISSN 0134-5486) is a quarterly publication of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS). The articles selected by the Editorial Council are chosen from books and journals originally prepared in the Russian language by authors from 30 institutes of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Statements of fact and opinion appearing in the journal are made on the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply the endorsement of the Editorial Council. Reprint permission: Editorial Council. Address: 26, Maronovsky pereulok, Moscow, 119991 GSP-1, Russia. SOCIAL SCIENCES (ISSN 0134-5486) is published quarterly by East View Information Services: 10601 Wayzata Blvd., Minneapolis, MN 55305, USA. Vol. 43, No. 1, 2012. Postmaster: Send address changes to East View Information Services: 10601 Wayzata Blvd., Minneapolis, MN 55305, USA. Orders are accepted by East View Information Services. Phone: (952) 252-1201; Toll-free: (800) 477-1005; Fax: (952) 252-1201; E-mail: [email protected] as well as by all major subscription agencies. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

The Soviet Critique of a Liberator's

THE SOVIET CRITIQUE OF A LIBERATOR’S ART AND A POET’S OUTCRY: ZINOVII TOLKACHEV, PAVEL ANTOKOL’SKII AND THE ANTI-COSMOPOLITAN PERSECUTIONS OF THE LATE STALINIST PERIOD by ERIC D. BENJAMINSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Eric D. Benjaminson Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History by: Julie Hessler Chairperson John McCole Member David Frank Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded: March 2018 ii © 2018 Eric D. Benjaminson iii THESIS ABSTRACT Eric D. Benjaminson Master of Arts Department of History March 2018 Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis investigates Stalin’s post-WW2 anti-cosmopolitan campaign by comparing the lives of two Soviet-Jewish artists. Zinovii Tolkachev was a Ukrainian artist and Pavel Antokol’skii a Moscow poetry professor. Tolkachev drew both Jewish and Socialist themes, while Antokol’skii created no Jewish motifs until his son was killed in combat and he encountered Nazi concentration camps; Tolkachev was at the liberation of Majdanek and Auschwitz. -

Internet Freedom in Vladimir Putin's Russia: the Noose Tightens

Internet freedom in Vladimir Putin’s Russia: The noose tightens By Natalie Duffy January 2015 Key Points The Russian government is currently waging a campaign to gain complete control over the country’s access to, and activity on, the Internet. Putin’s measures particularly threaten grassroots antigovernment efforts and even propose a “kill switch” that would allow the government to shut down the Internet in Russia during government-defined disasters, including large-scale civil protests. Putin’s campaign of oppression, censorship, regulation, and intimidation over online speech threatens the freedom of the Internet around the world. Despite a long history of censoring traditional media, the Russian government under President Vladimir Putin for many years adopted a relatively liberal, hands-off approach to online speech and the Russian Internet. That began to change in early 2012, after online news sources and social media played a central role in efforts to organize protests following the parliamentary elections in December 2011. In this paper, I will detail the steps taken by the Russian government over the past three years to limit free speech online, prohibit the free flow of data, and undermine freedom of expression and information—the foundational values of the Internet. The legislation discussed in this paper allows the government to place offending websites on a blacklist, shut down major anti-Kremlin news sites for erroneous violations, require the storage of user data and the monitoring of anonymous online money transfers, place limitations on 1 bloggers and scan the network for sites containing specific keywords, prohibit the dissemination of material deemed “extremist,” require all user information be stored on data servers within Russian borders, restrict the use of public Wi-Fi, and explore the possibility of a kill-switch mechanism that would allow the Russian government to temporarily shut off the Internet. -

Power Surge? Russia’S Power Ministries from Yeltsin to Putin and Beyond

Power Surge? Russia’s Power Ministries from Yeltsin to Putin and Beyond PONARS Policy Memo No. 414 Brian D. Taylor Syracuse University December 2006 The “rise of the siloviki ” has become a standard framework for analyzing Russian politics under President Vladimir Putin . According to this view, the main difference between Putin’s rule and that of former president Boris Yeltsin is the triumph of guns (the siloviki ) over money (the oligarchs). This approach has a lot to recommend it, but it also raises sever al important questions . One is the ambiguity embedded in the term siloviki itself . Taken from the Russian phrase for the power ministries ( silovie ministerstva ) or power structures ( silovie strukturi ), the word is sometimes used to refer to those ministrie s and agencies ; sometimes to personnel from those structures ; and sometimes to a specific “clan” in Russian politics centered around the deputy head of the presidential administration, former KGB official Igor Sechin . A second issue , often glossed over in the “rise of the siloviki ” story , is whether the increase in political power of men with guns has necessarily led to the strengthening of the state, Putin’s central policy goal . Finally, as many observers have pointed out, treating the siloviki as a unit – particularly when the term is used to apply to all power ministries or power ministry personnel – seriously overstates the coherence of this group. In this memo, I break down the rise of the siloviki narrative into multiple parts, focusing on three issues . First, I look at change over time, from the early 1990s to the present . -

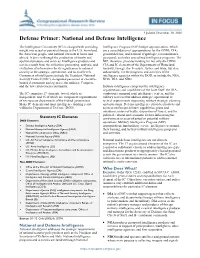

Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence

Updated December 30, 2020 Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence The Intelligence Community (IC) is charged with providing Intelligence Program (NIP) budget appropriations, which insight into actual or potential threats to the U.S. homeland, are a consolidation of appropriations for the ODNI; CIA; the American people, and national interests at home and general defense; and national cryptologic, reconnaissance, abroad. It does so through the production of timely and geospatial, and other specialized intelligence programs. The apolitical products and services. Intelligence products and NIP, therefore, provides funding for not only the ODNI, services result from the collection, processing, analysis, and CIA and IC elements of the Departments of Homeland evaluation of information for its significance to national Security, Energy, the Treasury, Justice and State, but also, security at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. substantially, for the programs and activities of the Consumers of intelligence include the President, National intelligence agencies within the DOD, to include the NSA, Security Council (NSC), designated personnel in executive NGA, DIA, and NRO. branch departments and agencies, the military, Congress, and the law enforcement community. Defense intelligence comprises the intelligence organizations and capabilities of the Joint Staff, the DIA, The IC comprises 17 elements, two of which are combatant command joint intelligence centers, and the independent, and 15 of which are component organizations military services that address strategic, operational or of six separate departments of the federal government. tactical requirements supporting military strategy, planning, Many IC elements and most intelligence funding reside and operations. Defense intelligence provides products and within the Department of Defense (DOD).