ISSN# 1203-9017 Summer 2011, Vol.16, No.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

Kokawadera Engi Kokawadera Engi Overview

Kokawadera engi Kokawadera engi Overview the Kokawadera engi emaki. We can assume its content from I. the kanbun account, the Kokawadera engi. The Kokawadera engi emaki (Illustrated Scroll of the II. Legends of the Kokawadera Temple) is a set of colored pic- tures on paper compiled into one scroll and consists of four The synopsis of the Engi is as follows. The Kokawadera text sections and five pictures. The beginning of the scroll Temple was founded in the first year of H¯oki. According to was burned in a fire, and the first pages of the remaining part the tradition of the elders, there was a hunter in this area, are badly scorched as well. Neither the authors nor the time named Otomo¯ no Kujiko. Devoting himself to hunting, Kujiko of production is known but it is considered to be a work of lived in the mountains and shot at game every night from a the early Kamakura period. The style of painting resembles platform he built in a valley. One night he saw a shining light, that of the Shigisan engi emaki. about the size of a large sedge hat. Frightened, Kujiko The Kokawadera Temple is an old temple in Wakayama stepped down from the platform and went near the light, but Prefecture, that, according to legend, a local hunter, Otomo¯ the light was gone. Yet when he went back to the platform, no Kujiko, built it in the first year of H¯oki (770). It is well the light began to shine again. This continued to happen for known as the fourth site of the Saikoku thirty-three temple three or four nights, so he cleaned the area, built a hut with pilgrimage circuit. -

Japanese Costume

JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago, 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military ( samurai ) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262 -

Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang Nihon Shakai No Seikatsu Ni Okeru Geta No Haki Kanshuu

TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 i Universitas Sumatera Utara TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dr. Diah Syafitri Handayani, M.Litt Prof. Hamzon Situmorang,M.S, Ph.D NIP:19721228 1999 03 2 001 NIP:19580704 1984 12 1 001 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara Disetujui Oleh, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Medan, September 2016 Departemen Sastra Jepang Ketua, Drs. Eman Kusdiyana, M.Hum NIP : 196009191988031001 iii Universitas Sumatera Utara KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dan syukur penulis panjatkan kepada Tuhan Yesus Kristus, oleh karena kasih karunia-Nya yang melimpah, anugerah,dan berkat-Nya yang luar biasa akhirnya penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini. Penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini yang merupakan syarat untuk mencapai gelar sarjana di Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara. Adapun skripsi ini berjudul “Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang”. Skripsi ini penulis persembahkan kepada orang tua penulis, Ibu Sonti Hutauruk, mama terbaik dan terhebat yang dengan tulus ikhlas memberikan kasih sayang, doa, perhatian, nasihat, dukungan moral dan materil kepada penulis sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan studi di Sastra Jepang USU, khususnya menyelesaikan skripsi ini. -

The Costume of Yamabushi "To Put on the Clothing of Yamabushi, Is to Put on the Personality of the Fudo Buddha" Something Always Practiced by the Shugenjas

Doctrines Costumes and Tools symbolisme | www.shugendo.fr Page 4 of 12 7. Not to break good manners and to accept insults from the Elders. 8. On level ground, not to have futile conversations (concerning Dharma or women) 9. Not to touch on the frivolous subjects, not to amuse with laughing at useless words or grievances. 10. When in bed, to fall asleep while using the nenju and reciting mantra) 11. Respect and obey the Veterans, Directors and Masters of Discipline, and read sutras aloud (the yamabushi in mountain have as a practice to speak with full lungs and the texts must be understandable) 12. Respect the regulations of the Directors and the Veterans. 13. Not to allow useless discussions. If the discussion exceeds the limits for which it is intended, one cannot allow it. 14. On level ground not to fall asleep while largely yawning (In all Japan the yawn is very badly perceived; a popular belief even says that the heart could flee the body by the yawn). 15. Those which put without care their sandals of straw (Yatsume-waraji, sandals with 8 eyelets) or which leave them in disorder will be punished with exceptional drudgeries. (It is necessary to have to go with sandals to include/understand the importance which they can have for a shugenja, even if during modern time, the "chika tabi" in white fabric replaced the sandals of straw at many shugenja. Kûban inside Kannen cave on Nevertheless certain Masters as Dai Ajari Miyagi Tainen continue to carry them for their comfort and Tomogashima island during 21 days the adherence which they offer on the wet stones. -

Shin Megami Tensei Persona: the Tabletop Roleplaying Game (Production Bible) V

Shin Megami Tensei Persona: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game (Production Bible) v. 0.5 (Beta 1 Hotfix) Principal Author: Will Canady. Supplementary Authors: breadotop, Sebastian Sung, Chris Robichaux, Daina Changelog: - Known Issues: [UNDER CONSTRUCTION] Chapter # - Character Creation [PLEASE WEAR A HARD HAT] Table of Contents [Under Construction] Forward What Kind of Game is This? What is Shin Megami Tensei? What is Persona? What Can You Expect? Character Creation What IS Persona: the RPG? Character Creation Checklist The Basics Dice System Jargon Pathos Classes? The Attributes Attribute Generation Attributes in Detail Muscle Finesse Intellect Charm Magic Power Aegis Background Persona Mechanics and the Major Arcana 2 [UNDER CONSTRUCTION] Chapter # - Character Creation [PLEASE WEAR A HARD HAT] CHARACTER CREATION “Elizabeth! We have a new group of users. They must have intriguing stories to tell…” -Igor, to a new party. Creating a character in Persona may seem daunting at first, especially if this is your first tabletop role-playing game. The sheer complexity of the rules can turn off newcomers to the genre. The jargon may seem incomprehensible and downright inane. That sentiment is totally understandable – tabletop is not for everyone. While a game like Persona is innately complex and due to a complex system, every effort will be made to make sure that character creation is made as simple as possible, and easy enough for anyone to pick up. Why? To give the prospective players, both old and new, an ease of access to the system, without being threatened with jargon and vague bullshit. To begin, let’s outline what Persona: the RPG is. -

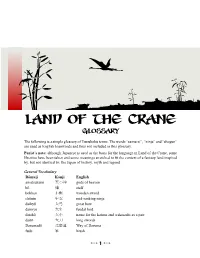

Land of the Crane Glossary

Land of the Crane Glossary The following is a simple glossary of Tsurukoku terms. The words “samurai”, “ninja” and “shogun” are used as English loanwords and thus not included in this glossary. Purist’s note: although Japanese is used as the basis for the language in Land of the Crane, some liberties have been taken and some meanings stretched to fit the context of a fantasy land inspired by, but not identical to, the Japan of history, myth and legend. General Vocabulary Rōmaji Kanji English amatsukami 天つ神 gods of heaven bō 棒 staff bokken 木剣 wooden sword chūnin 中忍 mid-ranking ninja daikyū 大弓 great bow daimyō 大名 feudal lord daishō 大小 name for the katana and wakizashi as a pair daitō 大刀 long swords Darumadō 達磨道 Way of Daruma fude 筆 brush Rōmaji Kanji English gaki 餓鬼 hungry ghost genin 下忍 low-ranking ninja geta 下駄 wooden clogs gō 業 karma hakama 袴 pleated divided skirt han 藩 fief hankyū 半弓 small bow hanyō 半妖 offspring of humans and supernatural creatures hara-ate 腹当 light armor haramaki 腹巻 medium armor harinezumi 猬 porcupine, hedgehog; porcupine race inkan 印鑑 personal seal irezumi 入墨 tattoo jashin 邪神 evil gods jō 杖 short staff jōnin 上忍 high-ranking ninja kama 鎌 sickle kami 神 gods, spirits, supernatural beings kami 紙 paper katana 刀 sword ki 気 spiritual or cosmic energy kidō 鬼道 Way of the Demons kimono 着物 kimono kitsune 狐 fox; fox people koku 石 unit of dry volume (about 180 liters or 5.11 bushels) kote 籠手 wrist and forearm guard kuge 公家 aristocracy, aristocrat kunai 苦無 small double-edged knife kuni 圀 country; also used to refer to large geographical -

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA682666 Filing date: 07/09/2015 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Randa Corp. Granted to Date 07/11/2015 of previous ex- tension Address 417 Fifth Avenue11th Floor New York, NY 10016 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- Mary L. Grieco, Safia A. Anand tion Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP 65 East 55th Street New York, NY 10022 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone:212-451-2300 Applicant Information Application No 79143045 Publication date 05/12/2015 Opposition Filing 07/09/2015 Opposition Peri- 07/11/2015 Date od Ends International Re- 1193211 International Re- 07/03/2013 gistration No. gistration Date Applicant J.B. Co., LTD. 3-20, Umeda 3-chome Osaka 530-0001, JAPAN Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 018. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: folding briefcases; shoulder bags; briefcases; carry-on bags; handbags; Boston bags; rucksacks; leather; fur pelts; artificial fur Class 025. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Evening dresses; children's wear, namely, rompers and one-piece garments; jackets; sweat pants; skirts; trousers; formalwear, namely, dresses, gowns, trousers -

SAMURAI Samurai Is a Word for a Japanese Warrior Class and for A

SAMURAI Samurai is a word for a Japanese warrior class and for a member of this class. The Japanese Way of the Warrior, has played a major role in shaping the behaviour of modern Japanese government, corporation, society, and individuals, as well as in shaping the modern martial arts within Japan and internationally. Samurai have been glorified in numerous films, books, comic series, TV shows and theatre plays. They are a source of fascination for adults and children all over the world. No figure is more emblematic of Japan and the Japanese than the samurai, the heroic warriors who lived by the code of bushido - the way of the samurai - founded upon loyalty, justice and honour. The warrior tradition in Japan is as ancient as the country itself, but the true samurai emerged during the late Heian period (mid 12th century) (when two powerful Japanese clans fought bitter wars against each other - the Taira and the Minamato) and thereafter ruled Japan for some 800 years. During this time, the classic Japanese martial arts evolved, and with them the bushido code. At that time the Japanese shogunate, a system of a military ruler, called the shogun was formed. Under the shogun the next hierarchy were the daimyo, local rulers comparable to dukes in Europe. The samurai were the military retainers of a daimyo. And finally you may have heard of ronin. Ronin are samurai without a master. According to historians the fierce fights between hostile clans and warlords was mainly a battle for land. Samurai Attributes and Privileges Samurai had several far-reaching privileges. -

Il Guerriero Giapponese Del Periodo Feudale, Fante O Cavaliere, Ha

armatura giapponese japanese armour 1) Short Fundoshi 2) Long Fundoshi 3) Shitagi and Obi 4) Kobakama 5) Tabi 6) Kyahan 7) Waraji 8) Sune-ate 9) Haidate 10) Yugake 11) Kote 12) Wakibiki 13) Do 14) Uwa-obi 15) Sode 16) Daisho 17) Nodowa and Hachimaki 18) Mempo, Kabuto Il guerriero giapponese del periodo feudale, fante o cavaliere, ha sempre The Japanese warrior of the feudal period, whether a foot soldier or on anteposto la sua abilità nel combattimento a qualsiasi forma di protezione horseback, always placed his own fighting skill above any form of protection che in un modo o nell’altro avesse potuto diminuirla. La libertà di that might restrict or diminish his effectiveness. Freedom of movement was movimento doveva essere comunque una clausola importante nella therefore an important consideration in the making of armour. realizzazione delle armature. La conformazione stessa dell’armatura The style and shape of successive models of Japanese armour, the fact that it giapponese, nei suoi modelli susseguenti quasi sempre lamellari, il suo was almost always lamellate and relatively light, and the nature of the peso contenuto, la qualità delle protezioni ed il loro relativo spessore, protection it offered indicate the importance its design placed on practicability; indicano come queste fossero state progettate all’insegna dell’agibilità it provided excellent defence against light weapons, projectiles such as arrows, fornendo una validissima difesa contro armi leggere, quali ad esempio and less, though still reasonably adequate protection from direct blows quelle da getto, come le frecce, ed una minore , ma sufficientemente valida, inflicted by spear or sword. -

Guide to the Japanese Textiles

' nxj jj g a LPg LIBRARY KHiW»s j vOU..-'.j U vi j w i^ITY PROVO, UTAH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/guidetojapaneset02vict . junihitoye Women’s Full Court Costume ( ) (From Tachibana no Morikuni, Yehon Shaho-bukuro.) Frontispiece.'] [See p. 48 [\JK ^84 .MS vol.S. VICTORIA AND AI.BERT MUSEUM DEPARTMENT OF TEXTILES GUIDE TO THE JAPANESE TEXTILES PART II.—COSTUME BY ALBERT J. KOOP LONDON : PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE, 1920. Publication No. i2ot First Printed,, March , 1920 Crown Copyright Reserved BAR B. LEE LIBRARY bright m young university PROVO, UTAH PREFATORY NOTE. HE present volume, forming the second part of the guide to the Japanese textiles, has been written, in his own time, T by Mr. A. Koop, Assistant in the Department of Metalwork, J. Honorary Librarian and member of Council of the Japan Society. The thanks of the Museum are due to Mr. Koop for this voluntary assistance. CECIL HARCOURT SMITH. March , 1920. CONTENTS. PAGE INTRODUCTION I I. ORDINARY COSTUME 2 Men’s Dress . 3 Women's Dress . 10 Children’s Dress . 15 Travelling Dress . 16 Coolies and Field Workers . 17 Weddings, Funerals, Etc. 18 II. COURT AND ECCLESIASTICAL DRESS .. .. 19 Court Dress for Men . 19 Accession Robes . 19 Sokutai Dress . 21 Ikwan Dress . 33 Naoshi, Ko-naoshi, . Hanjiri . 34 Kariginu, Hoi Hakucho . , 37 Hitatare . 38 . Daimon (Nunobitatare) . 40 . Sud . 40 ( . Suikan Suikan no Kariginu) . 41 ( . Choken Choken no Suikan) . 41 . Types of Yeboshi . 41 . Kamishimo . 42 Dress of Military Court Officials . 44 Shinto Festival .