Kokawadera Engi Kokawadera Engi Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w6w5wz Author Carter, Caleb Swift Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Caleb Swift Carter 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Place, Tradition and the Gods: Mt. Togakushi, Thirteenth through Mid-Nineteenth Centuries by Caleb Swift Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair This dissertation considers two intersecting aspects of premodern Japanese religions: the development of mountain-based religious systems and the formation of numinous sites. The first aspect focuses in particular on the historical emergence of a mountain religious school in Japan known as Shugendō. While previous scholarship often categorizes Shugendō as a form of folk religion, this designation tends to situate the school in overly broad terms that neglect its historical and regional stages of formation. In contrast, this project examines Shugendō through the investigation of a single site. Through a close reading of textual, epigraphical, and visual sources from Mt. Togakushi (in present-day Nagano Ken), I trace the development of Shugendō and other religious trends from roughly the thirteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries. This study further differs from previous research insofar as it analyzes Shugendō as a concrete system of practices, doctrines, members, institutions, and identities. -

Shinobi Notebook #3

Shinobi Notebook #3 http://passaic-bujinkan-buyu.setech-co.com Ninja Training The Togakure Ryu Ninpo, established approximately eight hundred years ago, is now in its 34th generation. The Ryu (style) exists today under the Bujinkan Association dedicated to teaching effective methods of self protection and promoting the self development and awareness of its members. Due to the stabilized nature of contemporary Japanese government and judicial systems, the Togakure ninja ryu no longer involves itself directly in combat or espionage work. Previous to the unification of Japan during the 16th century; however, it was necessary for Togakure ninja to operate out of south central Iga Province. At the height of the historical ninja period, the clan’s ninja operatives were trained in eighteen fundamental areas of expertise, beginning with this “physic purity” and progressing through a vast range of physical and mental skills. The eighteen levels of training were as follows: 1. Seishin Teki Kyoyo: Spiritual Refinement. 2. Taijutsu: Unarmed combat. Skills of daken-taijutsu or striking, kicking and blocking; jutaijutsu or grappling, choking and escaping the holds of others, and taihenjutsu or silent movement, rolling, leaping and tumbling assisted the Togakure ninja in life threatening, defensive situations. 3. Ninja Ken: Ninja Sword. Two distinct sword skills were required, “Fast draw” techniques centered around drawing the sword and cutting as a simultaneous defensive or attacking action. “Fencing” skills used the drawn sword in technique clashes with armed attackers. 4. Bo-Jutsu: Stick and staff fighting. 5. Shuriken-Jutsu: Throwing blades. Throwing blades were carried in concealed pockets and used as harassing weapons. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

ISSN# 1203-9017 Summer 2011, Vol.16, No.2

The Royal Visit of 1939 JCNM 2010.80.2.66 ISSN# 1203-9017 Summer 2011, Vol.16, No.2 The Royal Visit of 1939 by Bryan Akazawa 2 Building Community Partnerships by Beth Carter 3 A Visit to Mio Village and its Canada Immigration Museum by Stan Fukawa 4 World War II and Kika-nisei by Haruji (Harry) Mizuta 6 Two Unusual Artifacts! 11 From Kaslo to New Denver – A Road Trip by Carl Yokota 12 One Big Hapa Family by Christine Kondo 14 Jinzaburo Oikawa Descendents Survive Earthquake and Tsunami by Stan Fukawa 15 Growing Up on Salt Spring Island by Raymond Nakamura 16 “Just Add Shoyu” review by Margaret Lyons 20 Forever the Vancouver ASAHI Baseball Team! by Norifumi Kawahara 21 The Postwar M.A. Berry Growers Co-op by Stan Fukawa 22 Treasures from the Collections 24 CONTENTS ON THE COVER: The Royal Visit of 1939 by Bryan Akazawa he recent Canadian tour of William and Catherine, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, is a mirror image of the visit of Prince William’s great grandfather King George VI back in 1939. In both cases there was T a real concerted effort to strengthen ties between Canada and Britain, to increase and solidify bonds of trust and loyalty. During their visit, King George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth travelled 80 km by motorcade through the streets of Vancouver, including Powell Street. The Royal Couple was greeted by the proud and excited Japanese Canadian resi- dents. The community members were dressed in their finest clothing and elaborate kimono. -

Japanese Costume

JAPANESE COSTUME BY HELEN C. GUNSAULUS Assistant Curator of Japanese Ethnology FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CHICAGO 1923 Field Museum of Natural History DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Chicago, 1923 Leaflet Number 12 Japanese Costume Though European influence is strongly marked in many of the costumes seen today in the larger sea- coast cities of Japan, there is fortunately little change to be noted in the dress of the people of the interior, even the old court costumes are worn at a few formal functions and ceremonies in the palace. From the careful scrutinizing of certain prints, particularly those known as surimono, a good idea may be gained of the appearance of all classes of people prior to the in- troduction of foreign civilization. A special selection of these prints (Series II), chosen with this idea in mind, may be viewed each year in Field Museum in Gunsaulus Hall (Room 30, Second Floor) from April 1st to July 1st at which time it is succeeded by another selection. Since surimono were cards of greeting exchanged by the more highly educated classes of Japan, many times the figures portrayed are those known through the history and literature of the country, and as such they show forth the costumes worn by historical char- acters whose lives date back several centuries. Scenes from daily life during the years between 1760 and 1860, that period just preceding the opening up of the coun- try when surimono had their vogue, also decorate these cards and thus depict the garments worn by the great middle class and the military ( samurai ) class, the ma- jority of whose descendents still cling to the national costume. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262 -

Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang Nihon Shakai No Seikatsu Ni Okeru Geta No Haki Kanshuu

TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 i Universitas Sumatera Utara TRADISI PEMAKAIAN GETA DALAM KEHIDUPAN MASYARAKAT JEPANG NIHON SHAKAI NO SEIKATSU NI OKERU GETA NO HAKI KANSHUU SKRIPSI Skripsi Ini Diajukan Kepada Panitia Ujian Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Untuk Melengkapi salah Satu Syarat Ujian Sarjana Dalam Bidang Ilmu Sastra Jepang Oleh: AYU PRANATA SARAGIH 120708064 Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dr. Diah Syafitri Handayani, M.Litt Prof. Hamzon Situmorang,M.S, Ph.D NIP:19721228 1999 03 2 001 NIP:19580704 1984 12 1 001 DEPARTEMEN SASTRA JEPANG FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2016 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara Disetujui Oleh, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan Medan, September 2016 Departemen Sastra Jepang Ketua, Drs. Eman Kusdiyana, M.Hum NIP : 196009191988031001 iii Universitas Sumatera Utara KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dan syukur penulis panjatkan kepada Tuhan Yesus Kristus, oleh karena kasih karunia-Nya yang melimpah, anugerah,dan berkat-Nya yang luar biasa akhirnya penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini. Penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini yang merupakan syarat untuk mencapai gelar sarjana di Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara. Adapun skripsi ini berjudul “Tradisi Pemakaian Geta Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jepang”. Skripsi ini penulis persembahkan kepada orang tua penulis, Ibu Sonti Hutauruk, mama terbaik dan terhebat yang dengan tulus ikhlas memberikan kasih sayang, doa, perhatian, nasihat, dukungan moral dan materil kepada penulis sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan studi di Sastra Jepang USU, khususnya menyelesaikan skripsi ini. -

The Costume of Yamabushi "To Put on the Clothing of Yamabushi, Is to Put on the Personality of the Fudo Buddha" Something Always Practiced by the Shugenjas

Doctrines Costumes and Tools symbolisme | www.shugendo.fr Page 4 of 12 7. Not to break good manners and to accept insults from the Elders. 8. On level ground, not to have futile conversations (concerning Dharma or women) 9. Not to touch on the frivolous subjects, not to amuse with laughing at useless words or grievances. 10. When in bed, to fall asleep while using the nenju and reciting mantra) 11. Respect and obey the Veterans, Directors and Masters of Discipline, and read sutras aloud (the yamabushi in mountain have as a practice to speak with full lungs and the texts must be understandable) 12. Respect the regulations of the Directors and the Veterans. 13. Not to allow useless discussions. If the discussion exceeds the limits for which it is intended, one cannot allow it. 14. On level ground not to fall asleep while largely yawning (In all Japan the yawn is very badly perceived; a popular belief even says that the heart could flee the body by the yawn). 15. Those which put without care their sandals of straw (Yatsume-waraji, sandals with 8 eyelets) or which leave them in disorder will be punished with exceptional drudgeries. (It is necessary to have to go with sandals to include/understand the importance which they can have for a shugenja, even if during modern time, the "chika tabi" in white fabric replaced the sandals of straw at many shugenja. Kûban inside Kannen cave on Nevertheless certain Masters as Dai Ajari Miyagi Tainen continue to carry them for their comfort and Tomogashima island during 21 days the adherence which they offer on the wet stones. -

Shin Megami Tensei Persona: the Tabletop Roleplaying Game (Production Bible) V

Shin Megami Tensei Persona: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game (Production Bible) v. 0.5 (Beta 1 Hotfix) Principal Author: Will Canady. Supplementary Authors: breadotop, Sebastian Sung, Chris Robichaux, Daina Changelog: - Known Issues: [UNDER CONSTRUCTION] Chapter # - Character Creation [PLEASE WEAR A HARD HAT] Table of Contents [Under Construction] Forward What Kind of Game is This? What is Shin Megami Tensei? What is Persona? What Can You Expect? Character Creation What IS Persona: the RPG? Character Creation Checklist The Basics Dice System Jargon Pathos Classes? The Attributes Attribute Generation Attributes in Detail Muscle Finesse Intellect Charm Magic Power Aegis Background Persona Mechanics and the Major Arcana 2 [UNDER CONSTRUCTION] Chapter # - Character Creation [PLEASE WEAR A HARD HAT] CHARACTER CREATION “Elizabeth! We have a new group of users. They must have intriguing stories to tell…” -Igor, to a new party. Creating a character in Persona may seem daunting at first, especially if this is your first tabletop role-playing game. The sheer complexity of the rules can turn off newcomers to the genre. The jargon may seem incomprehensible and downright inane. That sentiment is totally understandable – tabletop is not for everyone. While a game like Persona is innately complex and due to a complex system, every effort will be made to make sure that character creation is made as simple as possible, and easy enough for anyone to pick up. Why? To give the prospective players, both old and new, an ease of access to the system, without being threatened with jargon and vague bullshit. To begin, let’s outline what Persona: the RPG is. -

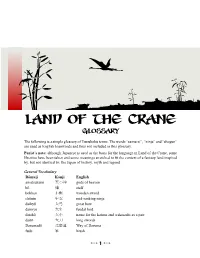

Land of the Crane Glossary

Land of the Crane Glossary The following is a simple glossary of Tsurukoku terms. The words “samurai”, “ninja” and “shogun” are used as English loanwords and thus not included in this glossary. Purist’s note: although Japanese is used as the basis for the language in Land of the Crane, some liberties have been taken and some meanings stretched to fit the context of a fantasy land inspired by, but not identical to, the Japan of history, myth and legend. General Vocabulary Rōmaji Kanji English amatsukami 天つ神 gods of heaven bō 棒 staff bokken 木剣 wooden sword chūnin 中忍 mid-ranking ninja daikyū 大弓 great bow daimyō 大名 feudal lord daishō 大小 name for the katana and wakizashi as a pair daitō 大刀 long swords Darumadō 達磨道 Way of Daruma fude 筆 brush Rōmaji Kanji English gaki 餓鬼 hungry ghost genin 下忍 low-ranking ninja geta 下駄 wooden clogs gō 業 karma hakama 袴 pleated divided skirt han 藩 fief hankyū 半弓 small bow hanyō 半妖 offspring of humans and supernatural creatures hara-ate 腹当 light armor haramaki 腹巻 medium armor harinezumi 猬 porcupine, hedgehog; porcupine race inkan 印鑑 personal seal irezumi 入墨 tattoo jashin 邪神 evil gods jō 杖 short staff jōnin 上忍 high-ranking ninja kama 鎌 sickle kami 神 gods, spirits, supernatural beings kami 紙 paper katana 刀 sword ki 気 spiritual or cosmic energy kidō 鬼道 Way of the Demons kimono 着物 kimono kitsune 狐 fox; fox people koku 石 unit of dry volume (about 180 liters or 5.11 bushels) kote 籠手 wrist and forearm guard kuge 公家 aristocracy, aristocrat kunai 苦無 small double-edged knife kuni 圀 country; also used to refer to large geographical -

Il Samurai. Da Guerriero a Icona

Il fiume di parole e d’immagini sul Giappone che si riversò a icona Da guerriero Il samurai. in Occidente dopo il 1860 lo configurò per sempre come l’idillica terra del Monte Fuji, coi laghi sereni punteggiati di vele, le geisha in pose seminude e gli indomabili samurai dalle misteriose armature. Il fascino che i guerrieri giapponesi e la loro filosofia di vita esercitarono sulla cultura del Novecento fu pari soltanto al desiderio di conoscere meglio la loro storia e i loro costumi, per svelare i segreti di una casta che prima Il samurai. di sconfiggere il nemico in battaglia aveva deciso, senza rinunciare ai piaceri della vita, di educare il corpo e la mente Da guerriero a icona a sconfiggere i propri limiti e le proprie paure, per raggiungere l’impalpabile essenza delle cose. a cura di Moira Luraschi 10 10 Antropunti Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Christian Kaufmann Antropunti € 32,00 Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Il samurai. Christian Kaufmann Da guerriero a icona La Collezione Morigi e altre recenti acquisizioni del MUSEC a cura di Antropunti Moira Luraschi 10 Sommario Note di trascrizione Prefazione 6 e altre avvertenze per la lettura Roberto Badaracco La trascrizione delle parole giapponesi Per la lettura delle parole trascritte ci si ba- segue il Sistema Hepburn modificato, fa- serà sulla fonologia italiana per le vocali, su Saggi I samurai. Guerrieri, politici, intellettuali 11 cendo eccezione per quei pochi casi in cui quella inglese per le consonanti. Si tenga Moira Luraschi un nome è entrato nell’uso corrente in una dunque presente che: ch è la c semiocclu- forma diversa (es.