Types of Japanese Folktales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku

LEAPING MONSTERS AND REALMS OF PLAY: GAME PLAY MECHANICS IN OLD MONSTER YARNS SUGOROKU by FAITH KATHERINE KRESKEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Faith Katherine Kreskey Title: Leaping Monsters and Realms of Play: Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Professor Akiko Walley Chairperson Professor Glynne Walley Member Professor Charles Lachman Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2012 ii © 2012 Faith Katherine Kreskey iii THESIS ABSTRACT Faith Katherine Kreskey Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture December 2012 Title: Leaping Monsters and Realms of Play: Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku Taking Utagawa Yoshikazu’s woodblock printed game board Monster Yarns as my case study, I will analyze how existing imagery and game play work together to create an interesting and engaging game. I will analyze the visual aspect of this work in great detail, discussing how the work is created from complex and disparate parts. I will then present a mechanical analysis of game play and player interaction with the print to fully address how this work functions as a game. -

Images and Words. an Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 771 SO 026 096 AUTHOR Lyons, Nancy Hai,:te; Ridley, Sarah TITLE Japan: Images and Words. An Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 66p.; Color slides and prints not included in this document. AVAILABLE FROM Education Department, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 ($24 plus $4.50 shipping and handling; packet includes six color slides and six color prints). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art; Art Activities; Art Appreciation; *Art Education; Foreign Countries; Grade 6; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Intermediate Grades; *Japanese Culture; *Language Arts; Painting (Visual Arts) ;Visual_ Arts IDENTIFIERS Japan; *Japanese Art ABSTRACT This packet, written for teachers of sixth-grade art and language arts courses, is designed to inspire creative expression in words and images through an appreciation for Japanese art. The selection of paintings presented are from the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interdisCiplinary approach, combines art and language arts. Lessons may be presented independently or together as a unit. Six images of art are provided as prints, slides, and in black and white photographic reproductions. Handouts for student use and a teacher's lesson guide also are included. Lessons begin with an anticipatory set designed to help students begin thinking about issues that will be discussed. A motivational activity, a development section, clusure, and follow-up activities are given for each lesson. Background information is provided at the end of each lesson. -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

No.766 (November Issue)

NBTHK SWORD JOURNAL ISSUE NUMBER 766 November, 2020 Meito Kansho: Examination of Important Swords Juyo Bijutsuhin, Important Cultural Property Type: Tachi Mei: Unji Length: 2 shaku 4 sun 4 bu 7 rin (74.15 cm) Sori: 9 bu 6 rin (2.9 cm) Motohaba: 9 bu 2 rin (2.8 cm) Sakihaba: 5 bu 9 rin (1.8 cm) Motokasane: 2 bu (0.6 cm) Sakikasane: 1 bu 2 rin (0.35 cm) Kissaki length: 8 bu 9 rin (2.7 cm) Nakago length: 6 sun 7 bu 3 rin (20.4 cm) Nakago sori: 7 rin (0.2 cm) Commentary This is a shinogi-zukuri tachi with an ihorimune. The width is standard, and the widths at the moto and saki are slightly different. There is a standard thickness, a large sori, and a chu-kissaki. The jigane has itame hada mixed with mokume and nagare hada, and the hada is barely visible. There are fine ji-nie, chikei, and jifu utsuri. The hamon is a wide suguha mixed with ko-gunome, ko-choji, and square features. There are frequent ashi and yo, and some places have saka-ashi. There is a tight nioiguchi with abundant ko-nie, and some kinsuji and sunagashi. The boshi on the omote is straight and there is a large round tip. The ura has a round tip, and there is a return. The nakago is suriage, and the nakago jiri is almost kiri, and the newer yasurime are sujichigai, and we cannot determine what style the old yasurime were. There are three mekugi-ana, On the omote, under the third mekugi-ana (the original mekugi-ana) there is a two kanji signature. -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age*

Klaus Antoni Universitdt Hamburg Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age* Abstract This article is concerned with a famous Japanese fairy tale, Momotaro, which was used during the war years in school readers as a primary part of nationalistic pro paganda. The tale and its central motif are analyzed and traced back through history to its earliest forms. Heroes from legend and history offered perfect identification patterns and images for the propagation of state ideals that were spread through education, the military, and war propaganda. Momotaro subtly- transmitted to young school pupils that which official Japan looked upon as the goal of its ideological education: through a fairy tale the gate to the “ Japanese spirit ” was opened. Key words: Momotaro — Japanese spirit — war propaganda Ryukyu Islands Asian Folklore Studies> Volume 50,1991:155-188. N a t io n a l is m a n d F o l k T r a d it io n in M o d e r n J a p a n F oundations of Japanese N ationalism APAN is a land rich in myths, legends, and fairy tales. It pos sesses a large store of traditional oral and literary folk literature, J which has not been accounted for or even recognized in the West. The very earliest traditional written historical documents contain narratives, themes, and motifs that express this rich tradition. Even though the Kojiki of the year 712, the oldest extant written source, was conceived of as a historical work at the time, it is a collection of pure myths, or at least the beginning portions are. -

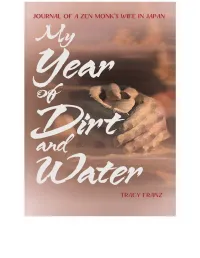

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

Iwasaka, Michiko and Barre Toelken. Ghosts and the Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends

BOOK REVIEWS 411 Iwasaka, Michiko and Barre Toelken. Ghosts and the Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1994. xx + 138 pages. Plates (color and b/w),bibliogra phy, index. Paper US$22.95; ISBN 0-87421-179-4. This small book introduces the reader to an understanding of Japanese culture by focusing on customs related to death and the ghost legends of Japan. As David Bufford states in his forward to this book, the merit of this endeavor lies in its description of Japanese death cus toms, translation of various ghost legends, and introduction of many illustrations of ghosts in Japanese art. He goes on to say that in this way the road is opened to an understanding of Japanese culture in a cross-cultural approach because the important conception of death lying in the background of Japanese everyday life is brought to the surface. The approach taken by the authors, that of relating ghost legends to death customs and from there going on to offer an interpretation of contemporary Japanese and their culture, may be baffling for Europeans and Americans alike. It could be seen negatively as nothing more than the quaint introductions to Japanese culture presented during a bygone era. For Japanese, however, this point of view is proper and for the most part very persuasive. If the book were translated into Japanese, the majority of Japanese readers would not find anything surprising or out of the ordinary. Its pages contain motifs that are familiar to them, things they have grown accustomed to seeing and hearing from their childhood. -

Masaki Kobayashi: KWAIDAN (1965, 183M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

March 10, 2020 (XL:10) Masaki Kobayashi: KWAIDAN (1965, 183m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Directed by Masaki Kobayashi Writing Credits Yôko Mizuki (screenplay), Lafcadio Hearn (novel) (as Yakumo Koizumi) Produced by Takeshi Aikawa, Shigeru Wakatsuki Music by Tôru Takemitsu Cinematography by Yoshio Miyajima Film Editing by Hisashi Sagara The film won the Jury Special Prize and was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film at the 1966 Academy Awards. CAST for the Palme d'Or at Cannes, and Samurai Rebellion “The Black Hair” (1967), and Kwaidan (1964), for which he, once again, Michiyo Aratama…First wife both won the Jury Special Prize and was nominated for the Misako Watanabe…Second Wife Palme d’Or. He was also nominated for the Palm d’Or for Rentarō Mikuni…Husband Nihon no seishun (1968). He also directed: Youth of the Son (1952), Sincerity (1953), Three Loves* (1954), “The Woman of the Snow” Somewhere Under the Broad Sky (1954), Beautiful Days Tatsuya Nakadai…Minokichi (1955), Fountainhead (1956), The Thick-Walled Room Jun Hamamura…Minokichi’s friend (1956), I Will Buy You (1956), Black River (1957), The *Keiko Kishi…the Yuki-Onna Inheritance (1962), Inn of Evil (1971), The Fossil (1974), Moeru aki (1979), Tokyo Trial* (Documentary) (1983), “Hoichi” and Shokutaku no nai ie* (1985).