Game Play Mechanics in Old Monster Yarns Sugoroku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O-Iwa's Curse

O-Iwa’s Curse Apparitions and their After-Effects in the Yotsuya kaidan Saitō Takashi 齋藤 喬 Nanzan Institute for Religion & Culture In traditional Japanese theater, ghosts appear in the shadowlands between the visible and the invisible. They often try to approach those who harmed or abused them in life to seek revenge with the aid of supernatural powers. In such scenes, the dead are visible as a sign of impending doom only to those who are the target of their revenge. An examination of the Yotsuya kaidan, one of the most famous ghost stories in all of Japanese literature, is a case in point. The story is set in the Edo period, where the protagonist, O-Iwa, is reputed to have put a curse on those around her with catastrophic results. Her legend spread with such effect that she was later immortalized in a Shinto shrine bearing her name. In a word, so powerful and awe-inspiring was her curse that she not only came to be venerated as a Shinto deity but was even memorialized in a Buddhist temple. There is no doubt that a real historical person lay behind the story, but the details of her life have long since been swallowed up in the mists of literary and artistic imagination. In this article, I will focus on the rakugo (oral performance) version of the tale (translated into English by James S. de Benneville in 1917) and attempt to lay out the logic of O-Iwa’s apparitions from the viewpoint of the narrative. ho is O-Iwa? This is the name of the lady of Tamiya house, which appeared in the official documents of Tokugawa Shogunate. -

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

Modelo Para Trabalhos Acadêmicos

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LÍNGUA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JAPONESA MARIA IVETTE JOB O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yōkaidō: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg versão corrigida Vol. I São Paulo 2021 MARIA IVETTE JOB O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yōkaidō: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg versão corrigida Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Filosofia do Departamento de Filosofia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Michiko Okano Ishiki São Paulo 2021 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Job, Maria Ivette J62t O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yôkaidô: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg / Maria Ivette Job; orientadora Michiko Okano Ishiki - São Paulo, 2021. 178 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Letras Orientais. Área de concentração: Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa. 1. Cultura Oriental - Japão. 2. Iconologia. 3. Mizuki, Shigeru, 1922-2015.. 4. Warburg, Aby M., 1866-1929.. I. Ishiki, Michiko Okano, orient. II. Título. UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE F FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ENTREGA DO EXEMPLAR CORRIGIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE Termo de Ciência e Concordância do (a) orientador (a) Nome do (a) aluno (a): Maria Ivette Job Data da defesa: 10/06/2021 Nome do Prof. -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan: Tra Ukiyoe E Cinema Horror Giapponese

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e civiltà dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan: Tra ukiyoe e cinema horror giapponese Relatore Ch.ma Prof.ssa Silvia Vesco Correlatrice Ch.ma Prof.ssa Maria Roberta Novielli Laureando Giulia Bianco Matricola 823588 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 私達が 明日に怯えるのは まだ見ぬものが 不安で仕方ないから でももしも わかりきった明日が やって来たなら つまらなすぎる そうでしょ? 恐れる事などない。 Il motivo per cui abbiamo paura del futuro è che non possiamo fare altro che provare ansia per ciò che ancora non conosciamo, ma se dovesse avverarsi un futuro che già conosciamo non sarebbe troppo noioso? Non c’è nulla da temere. Ayumi Hamasaki - Beautiful Day - 要旨 よんだいめつるやなんぼく 本論文は、江戸時代の絵師の浮世絵を通じて 、 四代目鶴屋南北 作 の 歌 舞 伎 狂 言 の とうかいどうよつやかいだん 『東海道四谷怪談』(1825 年初演)を描写することについての研究論文である。そして、様々な映画化 な か が わ の ぶ お し ん と う ほ う と よ た し ろ う 作品のうちで、中川信夫監督の『東海道四谷怪談』(新東宝、1959 年)と豊田四郎監督の『四谷怪談』 (東京映画、Illusion of Blood, 1965)のイコノグラフィーを分析する。 いわ た み や い え も ん よ つ や さ も ん 『東海道四谷怪談』は憤死したお岩さんの幽霊の物語である。浪人である民谷伊右衛門は、四谷左門を 殺した後で、左門の娘のお岩と結婚する。お岩は伊右衛門が父を殺した仇であることを知らないが、悪人で ある伊右衛門は女房の父の復讐をすることを約束する。しかし、伊右衛門は細々と暮らし続けることで疲れ い と う き へ い ている。それに、お岩は出産した後で、病気になる。一方では、隣屋敷の金持ちの伊藤喜兵衛には、伊右衛 門に惚れた孫娘・お梅がおり、お岩を殺す計略を企てる。伊右衛門には産後の薬と偽って毒薬を届ける。毒 を飲み干すと、お岩の面体が崩れてきた。今事実を知ったお岩は錯乱し、刀を振り回し、のどをかききってしま いだ う。伊右衛門を呪いながら、息が絶えている。恨みを抱いたお岩が亡霊になる。お岩の亡霊は復讐を図り、 犯罪の犯人を苦しめ始める。 まずは、幽霊の定義を明確にする必要がある。幽霊とは死後さまよっている霊魂である。その分類は多く、 ひ ご う し と つ 非業の死を遂げ、恨みを抱き、祟りをする怨霊、あるいは恨みがあり、相手に憑く生きている人の霊である生 霊などがある。 しゅんこうさい ほくしゅう 次に、浮世絵の様式の中で、役者絵が多数である。『東海道四谷怪談』の錦絵にある春好斎北洲(生 う た が わ く に よ し う た が わ く に さ だ 没年不詳)・歌川国芳(1798 年-1861 年)・歌川国貞(1786 -

Ghosts and the Fantastic in Literature and Film FALL 2018 (Updated 12.18).18

Topics in EALC: Ghosts and the Fantastic in Literature and Film FALL 2018 (updated 12.18).18 EALC 16000/CMST 24603/SIGN 26006 Class Meetings: M, W 3-4:20 Film Screenings: M 7-10 PM Cobb 307 Instructor: Judith Zeitlin [email protected] Wieboldt 406 Office hours: M, 4:30-6:30 pm Appointment sign up link: goo.gl/EteCJG Teaching Assistants: Jiayi Chen [email protected] office hours: T 1:00-2:00 pm, Ex Libris (Regenstein Library Cafe) Panpan Yang [email protected] office hours: F 1:00-2:00, Dollop Coffee Course Description What is a ghost? How and why are ghosts represented in particular forms in a particular culture at particular historical moments and how do these change as stories travel between cultures? How and why is traditional ghost lore reconfigured in the contemporary world? This course will explore the complex meanings, both literal and figurative, of ghosts and the fantastic in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean tales, plays, and films. Issues to be explored include: 1) the relationship between the supernatural, gender, and sexuality; 2) the confrontation of death and mortality; 3) collective anxieties over the loss of the historical past; 4) and the visualization of the invisible through art, theater, and cinema. &Required books (available for purchase at Seminary Coop bookstore or online) • Pu Songling. Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Trans. John Minford. Penguin Books, 2006 1 • Ueda Akinari. Tales of Moonlight and Rain. Trans. Anthony H. Chambers. Columbia University Press, 2007 • Judith Zeitlin. The Phantom Heroine: Ghosts and Gender in Seventeenth Century Chinese Literature. -

Mononoke, Yōkai E Donna Problematiche E Aspetti Sociali Del Giappone

Corso di Laurea in Lingue e civiltà dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea [LM20-14] Tesi di Laurea MONONOKE, YŌKAI E DONNA PROBLEMATICHE E ASPETTI SOCIALI DEL GIAPPONE Relatore Ch. Prof.ssa Maria Roberta Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof.ssa Paola Scrolavezza Laureando Valerio Pinos Matricola 859473 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 INDICE INDICE .............................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUZIONE .......................................................................................................... 3 要旨 ....................................................................................................................................... 5 MONONOKE: UN ESPERIMENTO FRA MISTERO E REALTÀ ........ 7 GLI ASPETTI STORICI E L’AUTORE 11 LO STILE D’ANIMAZIONE 15 LE QUESTIONI SOCIALI DELLA DONNA IN MONONOKE 31 YŌKAI: DEMONI DEL FOLKLORE E METAFORE SOCIALI............ 38 ZASHIKI-WARASHI: BAMBINI FANTASMA E IL DESIDERIO DI RINASCITA 41 NOPPERA-BŌ: SPIRITI SENZA VOLTO E ASSENZA DI IDENTITÀ 52 BAKENEKO: QUANDO LA VENDETTA PRENDE FORMA 64 DA MONONOKE ALLA REALTÀ: LA DONNA FRA OGGETTO, IDENTITÀ E DISCRIMINAZIONE ................................................................... 78 ABORTO E EMANCIPAZIONE DEL CORPO 80 L’IDENTITÀ DELLA DONNA NELLA FAMIGLIA 90 DISPARITÀ SUL POSTO DI LAVORO 100 CONCLUSIONI .......................................................................................................... 111 INDICE DELLE FIGURE ..................................................................................... -

Theorizing in Unfamiliar Contexts: New Directions in Translation Studies

Theorizing in Unfamiliar Contexts: New Directions in Translation Studies James Luke Hadley Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Language and Communication Studies April 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” 1 ABSTRACT This thesis attempts to offer a reconceptualization of translation analysis. It argues that there is a growing interest in examining translations produced outside the discipline‟s historical field of focus. However, the tools of analysis employed may not have sufficient flexibility to examine translation if it is conceived more broadly. Advocating the use of abductive logic, the thesis infers translators‟ probable understandings of their own actions, and compares these with the reasoning provided by contemporary theories. It finds that it may not be possible to rely on common theories to analyse the work of translators who conceptualize their actions in radically different ways from that traditionally found in translation literature. The thesis exemplifies this issue through the dual examination of Geoffrey Chaucer‟s use of translation in the Canterbury Tales and that of Japanese storytellers in classical Kamigata rakugo. It compares the findings of the discipline‟s most pervasive theories with those gained through an abductive analysis of the same texts, finding that the results produced by the theories are invariably problematic. -

Echoing Spirits: a Composition for Shakuhachi, 21-String Koto, and Orchestra

ECHOING SPIRITS: A COMPOSITION FOR SHAKUHACHI, 21-STRING KOTO, AND ORCHESTRA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC IN COMPOSITION MAY 2021 By William Watson Dissertation Committee: Chairperson, Donald Womack Thomas Osborne Takuma Itoh Kate McQuiston Mark Merlin TABLE OF CONTENTS • List of Tables……….…………………………………………………………………………iii • List of Examples.……….……….……….……….……….……….……….….….….….……iv • Note on Japanese Names and Terms…….……….……………………………………………vi • Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….1 • Motivation Behind the Instrumentation………………………………………………………..2 • Precedents………….……….…………….……………………………………………………4 • Cross-cultural Compositional Strategies…………….…………………………………………7 • Extramusical Ideas………………………………………………………………………….12 • Formal Application of Jo Ha Kyū……………………………………………………….…15 • Analysis of Echoing Spirits………………….………………………………………………..16 • Form………………………………………………………………………………………..16 • Harmonic Language………………………………………………………………………..29 • Orchestration……………………………………………………………………………….40 • Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….45 • Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………..46 "ii LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Dominant Jo Ha Kyū in Kodama……………………………………………………….18 Table 2. Subordinate Jo Ha Kyū within the Jo Phase of Kodama……………………………….18 Table 3: Subordinate Jo Ha Kyū within the Ha Phase of Kodama………………………………19 Table 4: Dominant Jo Ha Kyū in Kappa…………………………………………………………20 Table 5. Cyclic Structure of Kappa………………………………………………………………23 -

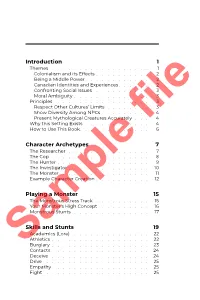

Introduction 1 Character Archetypes 7 Playing a Monster 15 Skills

Introduction 1 Themes..................1 Colonialism and its Effects..........2 Being a Middle Power............2 Canadian Identities and Experiences......2 Confronting Social Issues..........3 Moral Ambiguity..............3 Principles.................3 Respect Other Cultures’ Limits........3 Show Diversity Among NPCs.........4 Present Mythological Creatures Accurately...4 Why this Setting Exists............4 How to Use This Book.............6 Character Archetypes 7 The Researcher...............7 The Cop..................8 The Hunter.................9 The Investigator............... 10 The Monster................ 11 Example Character Creation.......... 12 Playing a Monster 15 The Monstrous Stress Track.......... 15 Your Monster’s High Concept......... 16 Monstrous Stunts.............. 17 Skills and Stunts 19 Academics (Lore).............. 22 Athletics.................. 22 SampleBurglary.................. 23 file Contacts.................. 24 Deceive.................. 24 Drive................... 25 Empathy.................. 25 Fight................... 25 Investigate................. 26 Notice................... 26 Physique.................. 27 Provoke.................. 27 Rapport.................. 28 Resources................. 28 Shoot................... 28 Stealth................... 30 Tech (Crafts)................ 30 Will.................... 31 Earth’s Secret History 33 Veilfall................... 33 Supernatural Immigration........... 35 The Cerulean Amendment.......... 36 Lifting the Veil................ 36 Organizations and NPCs 39 -

Yōkai Als Helden Der Populärkultur Am Beispiel Der Manga, 1978-2012“

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit „Yōkai als Helden der Populärkultur am Beispiel der Manga, 1978-2012“ Verfasser Stefan Fiala, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 843 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Japanologie UG2002 Betreuer: Mag. Dr. Bernhard Scheid 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Forschungsstand ............................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Forschungsfrage und Hypothese ...................................................................................... 8 1.3 Definition und Methode ................................................................................................. 10 1.3.1 Analyse ................................................................................................................... 14 1.4 Auswahl der Manga ....................................................................................................... 16 2 Eine kurze Geschichte der yōkai ........................................................................................... 18 2.1 Die Definition von yōkai ................................................................................................ 18 2.2 Die ersten yōkai-Sammlungen ....................................................................................... 21 2.3 Toriyama Sekien -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262