A Study of the Ritual Practices of the Izanagi-Ryū

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1423778527171.Pdf

Bahamut - [email protected] Based on the “Touhou Project” series of games by Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. http://www16.big.or.jp/~zun/ The Touhou Project and its related properties are ©Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. The Team Shanghai Alice logo is ©Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. Illustrations © their respective owners. Used without permission. Tale of Phantasmal Land text & gameplay ©2011 Bahamut. This document is provided “as is”. Your possession of this document, either in an altered or unaltered state signifies that you agree to absolve, excuse, or otherwise not hold responsible Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN and/or Bahamut, and/or any other individuals or entities whose works appear herein for any and/or all liabilities, damages, etc. associated with the possession of this document. This document is not associated with, or endorsed by Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. This is a not-for-profit personal interest work, and is not intended, nor should it be construed, as a challenge to Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN’s ownership of its Touhou Project copyrights and other related properties. License to distribute this work is freely given provided that it remains in an unaltered state and is not used for any commercial purposes whatsoever. All Rights Reserved. Introduction Choosing a Race (Cont.’d) What Is This Game All About? . 1 Magician . .20 Too Long; Didn’t Read Version . 1 Moon Rabbit . .20 Here’s the Situation . 1 Oni . .21 But Wait! There’s More! . 1 Tengu . .21 Crow Tengu . .22 About This Game . 2 White Wolf Tengu . .22 About the Touhou Project . 2 Vampire . .23 About Role-Playing Games . -

Etiquette Inside the Jingu Precinct How to Worship Kami Naiku Is The

Kodenchi (Site of the previous sanctuary) 古殿地 Main sanctuary A divine palace of Amaterasu-Omikami stands here. The Holy Mirror (a symbol of Amaterasu-Omikami) is enshrined inside the main sacred palace at the innermost courtyard of the main sanctuary and the main palace is enclosed with four rows of Naiku is the most venerable sanctuary in Japan. Here is a jinja (Shinto shrine) wooden fences. Pilgrims usually worship the enshrined kami in dedicated to Amaterasu-Omikami, the ancestral kami (Shinto deity) of the Imperial front of the gate of the third row of the fence. family. She was enshrined in Naiku about 2,000 years ago and has been revered as a guardian of Japan. Aramatsuri-no-miya There are 14 superior affiliated jinja which are revered next to the main sanctuaries of Naiku and Geku in Jingu. This jinja occupies the highest rank among them and is dedicated to a vigorous spirit of Geheiden Amaterasu-Omikami. (outer treasury) One of the auxiliary jinja of Naiku to store harvested rice for 外幣殿 offering to kami in rituals. An architectural style of this jinja is similar to that of the main palace of the main sanctuary but smaller in size. It is said that the style of jinja in Jingu derived from rice granary Jingu is a sanctuary to pray for public of ancient Japan. happiness. If someone have personal wish, he or she can dedicate a prayer by offering kagura (ceremonial music Kazahinomi-no-miya Rest house for Pilgrims. and dance) to kami of Jingu. Amulets Souvenirs and drink vending One of the superior affiliated jinja dedicated to a couple of Jingu can be obtained here. -

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

The Reliquaries of Hyrule: a Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time

Press Start The Reliquaries of Hyrule The Reliquaries of Hyrule: A Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time Jared Hansen University of Oregon Abstract This study is a semiotic and iconographic analysis of the sacred architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo, 1998). Through an analysis of the visual elements of the game, the researcher found evidence of visual metaphors that coded three temples as sacred spaces. This coding of the temples is accomplished through the symbolism of progression that matches the design of shrines and cathedrals, drawing on iconography and other symbolism associated with Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sacred architecture. Such indications of sacred spaces highlight the ways in which these virtual environments are designed to symbolize the progression of the player from secular to sacred, much like the player’s progression from zero to hero. By using the architecture and symbolism of the three aforementioned belief systems, Ocarina of Time signifies these temples as reliquaries—that is, sacred places that house reverential items as part of the apotheosis of the player. Keywords Art history; The Legend of Zelda; sacred space; symbolism; temple. Press Start 2021 | Volume 7 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hansen The Reliquaries of Hyrule Introduction The video game experiences that I remember and treasure most are the feelings I have within the virtual environments. -

Shinto Ritual Building Practices

Shinto Ritual Building Practices Philip E. Harding History of Art 681 The Ohio State University Shinto, the native religion of Japan, is a very diverse tradition yet one unified by certain ritual practices. Roughly speaking, Shinto can be divided into “folk Shinto” and “shrine Shinto,” but even within these divisions can be found considerable diversity. Every village has its own local traditions that operate independently from, yet related to the shrine tradition. (The folk activities take place on land owned by the shrine.) Within the shrine system there is also diversity, and today we can readily identify at least eighteen separate cults, each with its own style of shrine building1. Within Japan’s own official histories the shrine tradition, particularly the Imperial shrine tradition, has been given the most attention. This tradition experienced continental influences from China and was the one with which the Japanese upper class identified itself. Japan’s folk traditions, practiced in the locale where they first evolved, have largely gone without reference in Japan’s history of art and architecture. Both traditions, however, embrace many related themes and practices. One can find formal dualities expressed in the design of the folk forms and layouts of shrine buildings, as well as some shared motifs such as a “heart pillar.” Most significantly, both traditions periodically build and re-build sacred structures so that the particular built forms are simultaneously ephemeral and enduring – sharing in a kind of temporal immortality. These periodic rebuilding practices serve to reinforce cultural memory and place individuals into the larger stream of sacred time which transcends the temporal, constantly changing world of mortal time. -

Abstracts # DIJ-Mono 65 Blecken ENGLISH.Fm

LAURA BLECKEN “SELF-RESPONSIBILITY” IN JAPANESE SOCIETY: A CONCEPTUAL HISTORY AND DISCOURSE ANALYTIC STUDY APPLYING TOOLS FROM THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES * (ENGLISH SUMMARY) * This text is a summary of the PhD thesis on “‘Selbstverantwortung’ in der japa- nischen Gesellschaft: Eine begriffsgeschichtliche und diskursanalytische Unter- suchung mit Methoden der Digital Humanities”, composed under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Christian Oberländer at Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg. “Self-responsibility” in Japanese Society “SELF-RESPONSIBILITY” IN JAPANESE SOCIETY A CONCEPTUAL HISTORY AND DISCOURSE ANALYTIC STUDY APPLYING TOOLS FROM THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES (ENGLISH SUMMARY) Hostages in war zones, nuclear refugees from Fukushima and workers in pre- carious conditions are just a few examples of the many Japanese assigned per- sonal responsibility for their situation by the word jikosekinin. The term – lit- erally translated as “self-responsibility” – has become a keyword in contem- porary Japanese society. But what does jikosekinin mean, and how was it es- tablished in the Japanese language? This study examines this multi-faceted concept by combining methods of conceptual history and discourse analysis with tools from the digital humanities. It traces the word back to its roots and creates a model for different meanings of jikosekinin, through which various discourses converge. Finally, the study investigates how the word is used to- day by analyzing almost 40,000 blog posts. This procedure allows the omni- presence of jikosekinin in everyday life to be broken down and this concept, torn as it is between traditional moral values and the impacts of global neolib- eralism, to be discussed. 1) INTRODUCTION Around the year 2000, the word jikosekinin started to be called the “keyword of the era” (TAKIKAWA 2001: 32) and was described as “circulating with terrify- ing momentum” (ISHIDA 2001: 46). -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Department of Architecture

建築学セミナー Introduction to Architecture [Instructor] Hiroki Suzuki, Tatsuya Hayashi [Credits] 2 [Semester] 1st year Spring-Fall-Wed 1 [Course code] T1N001001 [Room] Respective laboratories *Please check the bulletin board of Department of Architecture , that will noticed where the lecture is held [Course objectives] Students and faculty members think together about study methods and attitudes as well as how to be aware of and interested in issues in the Department of Architecture. In particular, this course aims to teach the basic understanding of the fields of urban environmental and architectural planning as well as building structure design and to facilitate forming the basis of communication between the students and faculty members, by exposing the students in class in seminar format to educational research contents in each educational research field of the Department of Architecture. [Plans and Contents] Groups of about 10 students each will be formed. Each group will take a class in seminar format covering a total of four educational research fields and spend three to four weeks per field. The three to four week-long seminar for each field will be planned according to the characteristics of educational research in each field. [Textbooks and Reference Books] Not particularly [Evaluation] The grade will be determined by the average score ( if absent or not turned in) of exercises to be occasionally given during the lecture hours. Students will not be graded if they do not meet the rule of the Faculty of Engineering on the number of attendance days. [Remarks] Students will be assigned to their group in the first week. -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

Meguro Walking Map

Meguro Walking Map Meguro Walking Map Primary print number No. 31-30 Published February 2, 2020 December 6, 2019 Published by Meguro City Edited by Health Promotion Section, Health Promotion Department; Sports Promotion Section, Culture and Sports Department, Meguro City 2-19-15 Kamimeguro, Meguro City, Tokyo Phone 03-3715-1111 Cooperation provided by Meguro Walking Association Produced by Chuo Geomatics Co., Ltd. Meguro City Total Area Course Map Contents Walking Course 7 Meguro Walking Courses Meguro Walking Course Higashi-Kitazawa Sta. Total Area Course Map C2 Walking 7 Meguro Walking Courses P2 Course 1: Meguro-dori Ave. Ikenoue Sta. Ke Walk dazzling Meguro-dori Ave. P3 io Inok Map ashira Line Komaba-todaimae Sta. Course 2: Komaba/Aobadai area Shinsen Sta. Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji P7 0 100 500 1,000m Awas hima-dori St. 3 Course 3: Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area Kyuyamate-dori Ave. Walk the 1964 Tokyo Olympics P11 2 Komaba/Aobadai area Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji Shibuya City Tamagawa-dori Ave. Course 4: Himon-ya/Meguro-honcho area Ikejiri-ohashi Sta. Meguro/Shimomeguro area Walk among the history and greenery of Himon-ya P15 5 Walk among Edo period townscape Daikan-yama Sta. Course 5: Meguro/Shimomeguro area Tokyu Den-en-toshi Line Walk among Edo period townscape P19 Ebisu Sta. kyo Me e To tro Hibiya Lin Course 6: Yakumo/Midorigaoka area Naka-meguro Sta. J R Walk a green road born from a culvert P23 Y Yutenji/Chuo-cho area a m 7 Yamate-dori Ave. a Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n o Course 7: Yutenji/Chuo-cho area t e L Meguro City Office i Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n P27 e / S 2 a i k Minato e y Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area o in City Small efforts, L Yutenji Sta. -

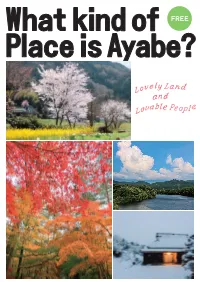

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt.