Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents

-1155 Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents Note: Chinese names are romanized according to the traditional Wade-Giles system. The pinyin romanization appears in parentheses. Chinese Names Japanese Names An Ch’ing-hsü (An Qingxu) An Keisho An Lu-shan (An Lushan) An Rokuzan Chang-an (Zhangan) Shoan Chang Chieh (Zhang Jie) Cho Kai Chang Liang (Zhang Liang) Cho Ryo Chang Wen-chien (Zhang Wenjian) Cho Bunken Chao (Zhao), King Sho-o Chao Kao (Zhao Gao) Cho Ko Ch’en Chen (Chen Zhen) Chin Shin Ch’eng (Cheng), King Sei-o Cheng Hsüan (Zheng Xuan) Tei Gen Ch’eng-kuan (Chengguan) Chokan Chia-hsiang ( Jiaxiang) Kajo Chia-shang ( Jiashang) Kasho Chi-cha ( Jizha) Kisatsu Chieh ( Jie), King Ketsu-o Chieh Tzu-sui ( Jie Zisui) Kai Shisui Chien-chen ( Jianzhen) Ganjin Chih-chou (Zhizhou) Chishu Chih-i (Zhiyi) Chigi z Chih Po (Zhi Bo) Chi Haku Chih-tsang (Zhizang) Chizo Chih-tu (Zhidu) Chido Chih-yen (Zhiyan) Chigon Chih-yüan (Zhiyuan) Shion Ch’i Li-chi (Qi Liji) Ki Riki Ching-hsi ( Jingxi) Keikei Ching K’o ( Jing Ko) Kei Ka Ch’ing-liang (Qingliang) Shoryo Ching-shuang ( Jingshuang) Kyoso Chin-kang-chih ( Jingangzhi) Kongochi 1155 -1156 APPENDIX D Ch’in-tsung (Qinzong), Emperor Kinso-tei Chi-tsang ( Jizang) Kichizo Chou (Zhou), King Chu-o Chuang (Zhuang), King So-o Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Soshi Chu Fa-lan (Zhu Falan) Jiku Horan Ch’ung-hua (Chonghua) Choka Ch’u Shan-hsin (Chu Shanxin) Cho Zenshin q Chu Tao-sheng (Zhu Daosheng) Jiku Dosho Fa-ch’üan (Faquan) Hassen Fan K’uai (Fan Kuai) Han Kai y Fan Yü-ch’i (Fan Yuqi) Han Yoki Fa-pao -

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

An Energetic Example of Bidirectional Sino-Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Transmission

religions Article From China to Japan and Back Again: An Energetic Example of Bidirectional Sino-Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Transmission Cody R. Bahir Independent Researcher, Palo Alto, CA 94303, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Sino-Japanese religious discourse, more often than not, is treated as a unidirectional phe- nomenon. Academic treatments of pre-modern East Asian religion usually portray Japan as the pas- sive recipient of Chinese Buddhist traditions, while explorations of Buddhist modernization efforts focus on how Chinese Buddhists utilized Japanese adoptions of Western understandings of religion. This paper explores a case where Japan was simultaneously the receptor and agent by exploring the Chinese revival of Tang-dynasty Zhenyan. This revival—which I refer to as Neo-Zhenyan—was actualized by Chinese Buddhist who received empowerment (Skt. abhis.eka) under Shingon priests in Japan in order to claim the authority to found “Zhenyan” centers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and even the USA. Moreover, in addition to utilizing Japanese Buddhist sectarianism to root their lineage in the past, the first known architect of Neo-Zhenyan, Wuguang (1918–2000), used energeticism, the thermodynamic theory propagated by the German chemist Freidrich Wilhelm Ost- wald (1853–1932; 1919 Nobel Prize for Chemistry) that was popular among early Japanese Buddhist modernists, such as Inoue Enryo¯ (1858–1919), to portray his resurrected form of Zhenyan as the most suitable form of Buddhism for the future. Based upon the circular nature of esoteric trans- mission from China to Japan and back to the greater Sinosphere and the use of energeticism within Neo-Zhenyan doctrine, this paper reveals the sometimes cyclical nature of Sino-Japanese religious influence. -

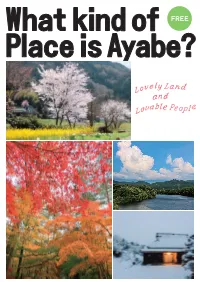

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Japan Studies Review

JAPAN STUDIES REVIEW Volume Nineteen 2015 Interdisciplinary Studies of Modern Japan Steven Heine Editor Editorial Board John A. Tucker, East Carolina University Yumiko Hulvey, University of Florida Matthew Marr, Florida International University Ann Wehmeyer, University of Florida Hitomi Yoshio, Florida International University Copy and Production María Sol Echarren Rebecca Richko Ian Verhine Kimberly Zwez JAPAN STUDIES REVIEW VOLUME NINETEEN 2015 A publication of Florida International University and the Southern Japan Seminar CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction i Re: Subscriptions, Submissions, and Comments ii ARTICLES Going Postal: Empire Building through Miniature Messages on German and Japanese Stamps Fabian Bauwens 3 Old, New, Borrowed, and Blue: Hiroshi Senju’s Waterfall Paintings as Intersections of Innovation Peter L. Doebler 37 Delightfully Sauced: Wine Manga and the Japanese Sommelier’s Rise to the Top of the French Wine World Jason Christopher Jones 55 “Fairness” and Japanese Government Subsidies for Sickness Insurances Yoneyuki Sugita 85 ESSAYS A “Brief Era of Experimentation”: How the Early Meiji Political Debates Shaped Japanese Political Terminology Bradly Hammond 117 The Night Crane: Nun Abutsu’s Yoru No Tsuru Introduced, Translated, and Annotated Eric Esteban 135 BOOK REVIEWS Scream from the Shadows: The Women’s Liberation Movement in Japan By Setsu Shigematsu Reviewed by Julia C. Bullock 169 Critical Buddhism: Engaging with Modern Japanese Buddhist Thought By James Mark Shields Reviewed by Steven Heine 172 Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination During the 1934 Tour of Japan By Robert K. Fitts Reviewed by Daniel A. Métraux 175 Supreme Commander: MacArther’s Triumph in Japan By Seymour Morris Reviewed by Daniel A. Métraux 177 CONTRIBUTORS/EDITORS i EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION Welcome to the nineteenth volume of the Japan Studies Review (JSR), an annual peer-reviewed journal sponsored by the Asian Studies Program at Florida International University Seminar. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

The Origins of Japanese Culture Uncovered Using DNA ―What Happens When We Cut Into the World of the Kojiki Myths Using the Latest Science

The Origins of Japanese Culture Uncovered Using DNA ―What happens when we cut into the world of the Kojiki myths using the latest science Miura Sukeyuki – Professor, Rissho University & Shinoda Kenichi – Director, Department of Anthropology, Japanese National Museum of Nature and Science MIURA Sukeyuki: The Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) has one distinguishing feature in the fact it includes a mixture of both Southern and Northern style myths. This is proof that Japanese culture was originally not only one culture, but rather came into existence while being influenced by its various surroundings; but when it comes to trying to seek out the origins of that culture, as we would expect, there are limits to how far we can get using only an arts and humanities-based approach. That’s where your (Professor Shinoda’s) area of expertise— molecular anthropology—comes in and corroborates things scientifically for us. Miura Sukeyuki , Professor, Rissho By analyzing the DNA remaining in ancient human skeletal remains, University your research closing in on the origins of the Japanese people is beginning to unravel when the Jomon and Yayoi peoples and so on came to the Japanese archipelago, where they came from, and the course of their movements, isn’t it? In recent times we’ve come to look forward to the possibility that, by watching the latest developments in scientific research, we may be able to newly uncover the origins of Japanese culture. SHINODA Kenichi: Speaking of the Kojiki , during my time as a student my mentor examined the bones of O-no-Yasumaro, who is regarded as being the person who compiled and edited it. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/3-4 Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship Jacqueline I. Stone This article places Nichiren within the context of three larger scholarly issues: definitions of the new Buddhist movements of the Kamakura period; the reception of the Tendai discourse of original enlightenment (hongaku) among the new Buddhist movements; and new attempts, emerging in the medieval period, to locate “Japan ” in the cosmos and in history. It shows how Nicmren has been represented as either politically conservative or rad ical, marginal to the new Buddhism or its paradigmatic figv/re, depending' upon which model of “Kamakura new Buddhism” is employed. It also shows how the question of Nichiren,s appropriation of original enlighten ment thought has been influenced by models of Kamakura Buddnism emphasizing the polarity between “old” and “new,institutions and sug gests a different approach. Lastly, it surveys some aspects of Nichiren ys thinking- about “Japan ” for the light they shed on larger, emergent medieval discourses of Japan relioiocosmic significance, an issue that cuts across the “old Buddhism,,/ “new Buddhism ” divide. Keywords: Nichiren — Tendai — original enlightenment — Kamakura Buddhism — medieval Japan — shinkoku For this issue I was asked to write an overview of recent scholarship on Nichiren. A comprehensive overview would exceed the scope of one article. To provide some focus and also adumbrate the signifi cance of Nichiren studies to the broader field oi Japanese religions, I have chosen to consider Nichiren in the contexts of three larger areas of modern scholarly inquiry: “Kamakura new Buddhism,” its relation to Tendai original enlightenment thought, and new relisdocosmoloei- cal concepts of “Japan” that emerged in the medieval period. -

Arising of Faith in the Human Body: the Significance of Embryological Discourses in Medieval Shingon Buddhist Tradition Takahiko Kameyama Ryukoku University, Kyoto

Arising of Faith in the Human Body: The Significance of Embryological Discourses in Medieval Shingon Buddhist Tradition Takahiko Kameyama Ryukoku University, Kyoto INTRODUCTION It was on the early Heian 平安 time period that the principal compo- nents of the Buddhist embryological knowledge, such as the red and white drops (shakubyaku nitei 赤白二渧) or the five developmental stages of embryo (tainai goi 胎内五位) from kalala (karara 羯剌藍) to praśākha (harashakya 鉢羅奢佉), were adopted into Japanese Esoteric Buddhist traditions.1 Since then, as discussed in the works of James H. Sanford2 or Ogawa Toyoo 小川豊生,3 these discourses with regard to the reproductive substances of a mother and father or the stages of fetal development within the womb were the indispensable interpreta- tive tools for both doctrine and practices of Shingon 眞言 and Tendai 天台Esoteric Buddhism.4 After being fully adopted, the embryological 1. As Toyoo Ogawa 小川豊生 points out, Enchin 円珍 (814–891), the Tendai Esoteric Buddhist monk during the early Heian time period, refers to the red and white drops and kalala, the mixture of these reproductive substances, in his Bussetsu kanfugenbosatsugyōbōkyō ki 佛説觀普賢菩薩行法經記 (Taishō, vol. 56, no. 2194). See Ogawa Toyoo, Chūsei nihon no shinwa moji shintai 中世日本の 神話・文字・身体 (Tokyo: Shinwasha 森話社, 2014), 305–6 and 331n6. 2. See James H. Sanford, “Wind, Waters, Stupas, Mandalas: Fetal Buddhahood in Shingon,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 24, nos. 1–2 (1997). 3. See Ogawa, Chūsei nihon no shinwa moji shintai. 4. For example, the fundamental non-dual nature between the womb realm mandala (taizōkai mandara 胎藏界曼荼羅) and that of diamond realm (kongōkai mandala 金剛界曼荼羅) was frequently represented by sexual intercourse and the mixture of the red and white drops.