Prayer Beads in Japanese Soto Sect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Dharma Devices, Non-Hermeneutical Libraries, and Robot-Monks : Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism Rambelli, Fabio University of California, Santa Barbara : Professor of Japanese Religions and IFS Endowed Chair Shinto Studies https://doi.org/10.5109/1917884 出版情報:Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University. 3, pp.57-75, 2018-03. 九州大学文学 部大学院人文科学府大学院人文科学研究院 バージョン: 権利関係: Dharma Devices, Non- Hermeneutical Libraries, and Robot-Monks: Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism FABIO RAMBELLI T is a well-documented fact—albeit perhaps not their technologies for that purpose.2 From a broader emphasized enough in scholarship—that Japa- perspective of more general technological advances, it nese Buddhism, historically, ofen has favored and is interesting to note that a Buddhist temple, Negoroji Icontributed to technological developments.1 Since its 根来寺, was the frst organization in Japan to produce transmission to Japan in the sixth century, Buddhism muskets and mortars on a large scale in the 1570s based has conveyed and employed advanced technologies in on technology acquired from Portuguese merchants.3 felds including temple architecture, agriculture, civil Tus, until the late seventeenth century, when exten- engineering (such as roads, bridges, and irrigation sive epistemological and social transformations grad- systems), medicine, astronomy, and printing. Further- ually eroded the Buddhist monopoly on technological more, many artisan guilds (employers and developers advancement in favor of other (ofen competing) social of technology)—from sake brewers to sword smiths, groups, Buddhism was the main repository, benefciary, from tatami (straw mat) makers to potters, from mak- and promoter of technology. ers of musical instruments to boat builders—were more It should come as no surprise, then, that Buddhism or less directly afliated with Buddhist temples. -

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” E‐Book

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Padmakumara website would like to gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for contributing to the production of “Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” e‐book. Translator: Alice Yang, Zhiwei Editor: Jason Yu Proofreader: Renée Cordsen, Jackie Ho E‐book Designer: Alice Yang, Ernest Fung The Padmakumara website is most grateful to Living Buddha Lian‐sheng for transmitting such precious dharma. May Living Buddha Lian‐sheng always be healthy and continue to teach and liberate beings in samsara. May all sentient beings quickly attain Buddhahood. Om Guru Lian‐Sheng Siddhi Hum. Exhaustive research was undertaken to ensure the content in this e‐book is accurate, current and comprehensive at publication time. However, due to differing individual interpreting skills and language differences among translators and editors, we cannot be responsible for any minor wording discrepancies or inaccuracies. In addition, we cannot be responsible for any damage or loss which may result from the use of the information in this e‐book. The information given in this e‐book is not intended to act as a substitute for the actual lineage and transmission empowerments from H.H. Living Buddha Lian‐sheng or any authorized True Buddha School master. If you wish to contact the author or would like more information about the True Buddha School, please write to the author in care of True Buddha Quarter. The author appreciates hearing from you and learning of your enjoyment of this e‐book and how it has helped you. We cannot guarantee that every letter written to the author can be answered, but all will be forwarded. -

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

The Kasāya Robe of the Past Buddha Kāśyapa in the Miraculous Instruction Given to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan (596~667)

中華佛學學報第 13.2 期 (pp.299-367): (民國 89 年), 臺北:中華佛學研究所,http://www.chibs.edu.tw Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, No. 13.2, (2000) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies ISSN: 1017-7132 The Kasāya Robe of the Past Buddha Kāśyapa in the Miraculous Instruction Given to the Vinaya Master Daoxuan (596~667) Koichi Shinohara Professor, McMaster University Summary Toward the end of his life, in the second month of the year 667, the eminent vinaya master Daoxuan (596~667) had a visionary experience in which gods appeared to him and instructed him. The contents of this divine teaching are reproduced in several works, such as the Daoxuan lüshi gantonglu and the Zhong Tianzhu Sheweiguo Zhihuansi tujing. The Fayuan zhulin, compiled by Daoxuan's collaborator Daoshi, also preserves several passages, not paralleled in these works, but said to be part of Daoxuan's visionary instructions. These passages appear to have been taken from another record of this same event, titled Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji. The Fayuan zhulin was completed in 668, only several months after Daoxuan's death. The Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji, from which the various Fayuan zhulin passages on Daoxuan's exchanges with deities were taken, must have been compiled some time between the second lunar month in 667 and the third month in the following year. The quotations in the Fayuan zhulin from the Daoxuan lüshi zhuchi ganying ji take the form of newly revealed sermons of the Buddha and tell stories about various objects used by the Buddha during his life time. -

Informed Textual Practices?

INFORMED TEXTUAL PRACTICES? INFORMED TEXTUAL PRACTICES? A STUDY OF DUNHUANG MANUSCRIPTS OF CHINESE BUDDHIST APOCRYPHAL SCRIPTURES WITH COLOPHONS By RUIFENG CHEN, B.Ec., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Ruifeng Chen, September 2020 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2020) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Informed Textual Practices? A Study of Dunhuang Manuscripts of Chinese Buddhist Apocryphal Scriptures with Colophons AUTHOR: Ruifeng Chen B.Ec. (Zhejiang Normal University) M.A. (Zhejiang Normal University) SUPERVISOR: Professor James A. Benn, Ph.D. NUMBER OF PAGES: xv, 342 ii ABSTRACT Taking Buddhist texts with colophons copied at Dunhuang (4th–10th century C.E.) as a sample, my dissertation investigates how local Buddhists used Chinese Buddhist apocrypha with respect to their contents, and whether they employed these apocrypha differently than translated Buddhist scriptures. I demonstrate that not all of the practices related to Buddhist scriptures were performed simply for merit in general or that they were conducted without awareness of scriptures’ contents. Among both lay Buddhist devotees and Buddhist professionals, and among both common patrons and highly-ranking officials in medieval Dunhuang, there were patrons and users who seem to have had effective approaches to the contents of texts, which influenced their preferences of scriptures and specific textual practices. For the patrons that my dissertation has addressed, apocryphal scriptures did not necessarily meet their needs more effectively than translated scriptures did. I reached these arguments through examining three sets of Buddhist scriptures copied in Dunhuang manuscripts with colophons. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

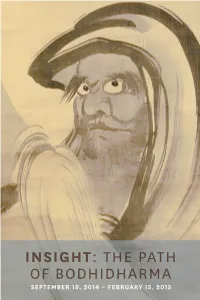

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Devotion in Buddhism

DEVOTION IN BUDDHISM BY ANANDA METTEYA (ALLAN BENNETT) A<A< www.astrumargenteum.org DEVOTION IN BUDDHISM There are few circumstances more surprising to the student of comparative religion than the fact that, in the pure Buddhism of the Theravāda, which constitutes the national religion of Burma, he finds exhibited, both in the scriptural sources of the religion, and in the lives of the people who follow it, an all pervading spirit of intense devotion -a spirit of loving adoration, directed to The Buddha, His Teaching and His Brotherhood of Monks, such as is hardly to be equaled, and certainly not to be excelled, in any of the world's theistic creeds. To one, especially, who has been brought up in the modern western environment, this earnest devotion, this spirit of adoration, seems almost the last feature he would expect to find in a religion so intellectually and so logically sound as this our Buddhist faith. He has been accustomed to regard this deep emotion of adoration, as the peculiar prerogative of the Godhead of whatever forms of religion he has studied. So to find it in so marked a degree, in so predominant a measure, in a creed from which all concept of an animistic Deity is absent, appears as well-nigh the most remarkable, as it was the most unexpected feature, of the many strange and novel characteristics of this altogether unique form of religious teaching. That trusting worship, that self abnegating spirit of devotion in which, in the rest of the great world-religions, the devotee loses himself in thoughts of the glory, power and love of the Supreme Being of whom they teach, so far from being absent here, whence all thought of such a Being is banished, actually exists in a most superlative degree. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately.