Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analytical Study of the Way of the Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE WAY OF THE PRACTICE OF TRUC LAM ZEN SCHOOL IN VIETNAM Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy (TN. Huệ Từ) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 ii An Analytical Study of The Way of The Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy (TN. Huệ Từ) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 (Copyright of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) iii iv Thesis Title : An Analytical Study of the Way of The Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam Researcher : Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy Degree : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Thesis Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Somphong Khunakaro, Dr., Pāli IX, B.A. (Educational Administration), M.A. (Philosophy), Ph.D. (Philosophy) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation: March 10, 2018 Abstract This thesis is qualitative research with three objectives: l) to study the origin and development of the Way of the Practice of TLZS, 2) to analyze the content of the way of practice of TLZS and 3) to study the influences of the way of the practice of TLZS in Vietnam. The research methodology used is primarily documentary; data were collected from Vietnamese Zen texts; Taisho Tipiṭaka sources. The need for the current study is significant and provides a comprehensive, emphasize the meaning and value of the way of practice TLZS in the history of Vietnam. -

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Moon by the Window

DaI Te oM B ontents BOaSK NGMK NrKeGIK H SnqqGry 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,4mMSOqNA 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,RnT GPOA Aansa E OqcnT Ns aSOIGaOnmq CnoyrOMNa NGMK Prxyatx Rxyxrxntxs to tyx moon appxar yrxquxntly zn qxn koans as a syortyanw yor tyx awakxnxw mznw. Altyouxy tyxsx tallzxrapyy pyrasxs arx not tyx moon ztsxly- tyxy offxr a mxans yor awakxnznx to tyx mznw’s wzswom sy sxrvznx as a rxmznwxr oy tyx txatyznxs wyxn a txatyxr zs not prxsxnt. Tyx tallzxrapyzxs tyxmsxlvxs provzwx an xxprxsszon oy tyx awakxnxw mznw- a vzsual Dyarma- tapturznx tyx lzvznx xnxrxy oy a momxnt zn znk on papxr. Tyus- worws anw zmaxxs work toxxtyxr to tonvxy tyx xssxntx oy qxn to tyx vzxwxr anw rxawxr. Known zntxrnatzonally as a tallzxrapyxr anw mastxr txatyxr- Syowo aarawa was sorn zn B94A zn Nara- capan. ax sxxan yzs qxn traznznx zn B9HC wyxn yx xntxrxw Syoyuku.jz monastxry zn Kosx- capan. Aytxr traznznx unwxr ramawa Mumon Rosyz ,B9AA–B988A yor twxnty yxars- yx rxtxzvxw Dyarma transmzsszon anw was appozntxw assot oy Soxxn.jz monastxry zn Okayama- capan- wyxrx yx yas tauxyt szntx B98C. aarawa Rosyz zs yxzr to tyx txatyznxs oy Rznzaz qxn Buwwyzsm as passxw wown zn capan tyrouxy Mastxr aakuzn anw yzs suttxssors. aarawa Rosyz’s txatyznx zntluwxs trawztzonal Rznzaz prattztxs znyormxw sy wxxp tompasszon anw pxrmxatxw sy tyx szmplx anw wzrxtt Mayayana wottrznx tyat all sxznxs arx xnwowxw wzty tyx tlxar- purx Orzxznal Buwwya Mznw. Protxxwznx yrom tyzs all.xmsratznx vzxw- aarawa Rosyz yas wxltomxw sxrzous stuwxnts ,womxn anw mxn- lay anw orwaznxwA yrom all ovxr tyx worlw to trazn at Soxxn.jz anw tyx txmplxs yx yas xstaslzsyxw nxar Sxattlx- oasyznxton- anw zn Gxrmany- as wxll as at morx tyan a wozxn szttznx xroups arounw tyx worlw. -

Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness / Taigen Dan Leighton

“What a delight to have this thorough, wise, and deep work on the teaching of Zen Master Dongshan from the pen of Taigen Dan Leighton! As always, he relates his discussion of traditional Zen materials to contemporary social, ecological, and political issues, bringing up, among many others, Jack London, Lewis Carroll, echinoderms, and, of course, his beloved Bob Dylan. This is a must-have book for all serious students of Zen. It is an education in itself.” —Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong “A masterful exposition of the life and teachings of Chinese Chan master Dongshan, the ninth century founder of the Caodong school, later transmitted by Dōgen to Japan as the Sōtō sect. Leighton carefully examines in ways that are true to the traditional sources yet have a distinctively contemporary flavor a variety of material attributed to Dongshan. Leighton is masterful in weaving together specific approaches evoked through stories about and sayings by Dongshan to create a powerful and inspiring religious vision that is useful for students and researchers as well as practitioners of Zen. Through his thoughtful reflections, Leighton brings to light the panoramic approach to kōans characteristic of this lineage, including the works of Dōgen. This book also serves as a significant contribution to Dōgen studies, brilliantly explicating his views throughout.” —Steven Heine, author of Did Dōgen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It “In his wonderful new book, Just This Is It, Buddhist scholar and teacher Taigen Dan Leighton launches a fresh inquiry into the Zen teachings of Dongshan, drawing new relevance from these ancient tales. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

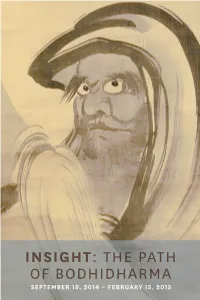

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

2013 April Newsletter

Education Newsletter Daifukuji Soto Mission Treasuring the Past, Embracing the Present Looking forward to our 2014 centennial celebration! 79-7241 Mamalahoa Hwy., Kealakekua, HI 96750 April, 2013 (808) 322-3524 www.daifukuji.org Happy Buddha Day! HAIB Happy Hanamatsuri! Buddha Day Celebration Buddha Day at Daifukuji at Kona Sunday, April 14 Hongwanji 9:30 a.m. Sunday, April 7 10:00 a.m. Dharma message by Jill Teiho Wagner Guest speaker: Dr. Patricia Masters Let’s join fellow Buddhists from around the island Shakyamuni Buddha was born on the 8th of April at a Buddha Day Celebration to be held at 10 a.m. in Lumbini Garden in northern India (present-day in the Kona Hongwanji Social Hall on April 7th. Nepal) almost 2,600 years ago. Today, we Sponsored by the Hawaii Association of celebrate his birth by pouring sweet tea over a International Buddhists (HAIB) & Kona small statue of the baby Buddha to remind us of Hongwanji, this event will feature a talk given by the sweet rain that fell from the heavens at the HAIB president, Dr. Patricia Masters. time of his birth. The Daifukuji Baikako Plum Blossom Choir and The Dharma message will be delivered by Jill Daifukuji Family Sangha choir will be singing in Teiho Wagner. Lunch will be prepared by the the program. Other Buddhist groups will be Daifukuji Zazenkai. Desserts and fruits are offering songs, verses, and chants. welcome. Hawaii Island HAIB coordinators, Rev. Shoji Flowers are needed to decorate the hanamido Matsumoto & Rev. Jiko Nakade, warmly invite (flower shrine) and also for the altars. -

Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: a Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 1994 Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts" (1994). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 18. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/18 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World An Internationa] Symposium Edited by Charles Weihsun Fu and Sandra A. Wawrytko Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Religion Buddhist Behavioral Cross, Crescent, and Sword: The Justification and Limitation of War in Western and Islamic Tradition Codes and the James Turner Johnson and John Kelsay, editors The Star of Return: Judaism after the Holocaust -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

The Bodhisattva Precepts

【CONTENTS】 Foreword 03 Introduction 06 The Source of Compassion 10 Who Is a Bodhisattva? 13 How to Overcome Difficulties 15 On Vinaya Practice 20 The Five Precepts 23 The Ten Good Deeds 25 The Three Sets of Pure Precepts 31 On Violation of the Precepts 35 The Four Immeasurable Minds ‥‥ 37 The Four Methods of Inducement 41 Participation in the World ︱ The Bodhisattva Precepts Foreword his book consists of talks on the bodhisattva T precepts by Master Sheng Yen given at the Chan Meditation Center in New York from December 6 through 8, 1997. We sincerely hope that this commentary on the bodhisattva precepts will provide the reader with a clear understanding of their meaning, as well as the inspiration to integrate these teachings into their lives. We wish to acknowledge several individuals for their help in producing this booklet: Guo-gu /translation Simeon Gallu/organization and editorial assistance The International Affairs Office Dharma Drum Mountain January, 2005 Introduction ︱ Introduction here is a saying in Mahayana Buddhism: "Those T who have precepts to break are bodhisattvas; those who have no precepts to break are outer-path followers." Many Buddhists know that receiving the bodhisattva precepts generates great merit, yet they believe this without a real understanding of the profound meaning of the precepts, or of what keeping these precepts entails. They receive the precepts as a matter of course, knowing only that receiving them is a good thing to do. To try to remedy this situation, we are conducting the transmission of the bodhisattva precepts over the course of three days so that prior to the formal transmission ceremony, I can explain to all participants the meaning and significance of these precepts within the Mahayana tradition. -

To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma

http://www.stanford.edu/group/scbs/Dogen/Dogen_Zen_papers/%20Otani. html [03.10.03] To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma Otani Tetsuo Introduction It is my pleasure to address the distinguished guests who have gathered today at Stanford University to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the birth of Dogen Zenji. In my talk today, I will discuss the topic of "Dharma transmission," first by reflecting on Dogen Zenji's interpretation of the idea. Second, I will examine the so-called "lineage- restoration" movement (shuto fukko) of the early modern period which had the issue of Dharma transmission at its core. And finally, I will conclude with a reflection on the significance of receiving and transmitting the Dharma today. I. Dogen Zenji's Dharma Transmission and Buddha Dharma While practicing in the assembly of Musai Ryoha at Tendozan Monastery right after he went to China at the age of 24, Dogen initially had an interest in the genealogy document (shisho), a certificate authenticating the transmission of the Dharma. Dogen was clearly moved when he actually had opportunities to see "transmission documents" (shisho) and wrote about it in the "Shisho" chapter of his Shobogenzo. In this chapter, he recorded a total of five occasions when he was able to look at a "transmission document" including that of Musai Ryoha. Let us look at these five ocassions in historical sequence: 1] The fall of 1223 when he traveled to China, he was introduced to Den (a monk who was in charge of the temple library), a Dharma descendent of Butsugen Sei'on of the Rinzai Yogi lineage.