Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

PUBLICATION of SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS

PUBLICATION OF SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS TALKS 3 The Gift of Zazen BY Shunryu Suzuki-roshi 16 Practice On and Off the Cushion BY Anna Thom 20 The World Is Vast and Wide BY Gretel Ehrlich 36 An Appropriate Response BY Abbess Linda Ruth Cutts POETRY AND ART 4 Kannon in Waves BY Dan Welch (See also front cover and pages 9 and 46) 5 Like Water BY Sojun Mel Weitsman 24 Study Hall BY Zenshin Philip Whalen NEWS AND FEATURES 8 orman Fischer Revisited AN INTERVIEW 11 An Interview with Annie Somerville, Executive Chef of Greens 25 Projections on an Empty Screen BY Michael Wenger 27 Sangha-e! 28 Through a Glass, Darkly BY Alan Senauke 42 'Treasurer's Report on Fiscal Year 2002 DY Kokai Roberts 2 covet WNO eru 111 -ASSl\ll\tll.,,. o..N WEICH The Gi~ of Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi December 14, 1967-Los Altos, California JAM STILL STUDYING to find out what our way is. Recently I reached the conclusion that there is no Buddhism or Zen or anythjng. When I was preparing for the evening lecture in San Francisco yesterday, I tried to find something to talk about, but I couldn't; then I thought of the story 1 was told in Obun Festival when I was young. The story is about water and the people in Hell Although they have water, the people in hell cannot drink it because the water burns like fire or it looks like blood, so they cannot drink it. -

Fall 1969 Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN •CENTER Volume Vilt Nos. 1-2 Fall 1969 This fellow was a son of Nobusuke Goemon Ichenose of Takahama, the province of Wakasa. His nature was stupid and tough. When he was young, none of his relatives liked him. When he was twelve years old, he was or<Llined as a monk by Ekkei, Abbot of Myo-shin Monastery. Afterwards, he studied literature under Shungai of Kennin Monastery for three years, and gained nothing. Then he went to Mii-dera and studied Tendai philosophy under Tai-ho for. a summer, and gained nothing. After this, he went to Bizen and studied Zen under the old teacher Gisan for one year, and attained nothing. He then went to the East, to Kamakura, and studied under the Zen master Ko-sen in the Engaku Monastery for six years, and added nothing to the aforesaid nothingness. He was in charge of a little temple, Butsu-nichi, one of the temples in Engaku Cathedral, for one year and from there he went to Tokyo to attend Kei-o College for one year and a half, making himself the worst student there; and forgot the nothingness that he had gained. Then he created for himself new delusions, and came to Ceylon in the spring of 1887; and now, under the Ceylon monk, he is studying the Pali Language and Hinayana Buddhism. Such a wandering mendicant! He ought to <repay the twenty years of debts to those who fed him in the name of Buddhism. July 1888, Ceylon. Soyen Shaku c.--....- Ocean Wind Zendo THE KOSEN ANO HARADA LINEAOES IN AMF.RICAN 7.llN A surname in CAI':> andl(:attt a Uhatma heir• .l.incagea not aignilleant to Zen in Amttka arc not gi•cn. -

Zen Is a Form of Buddhism That Developed First in China Around the Sixth Century CE and Then Spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan

Zen Zen is a form of Buddhism that developed first in China around the sixth century CE and then spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan. The term Zen is just the Japanese way of saying the Chinese word Chan ( 禪 ), which is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word Dhyāna (Jhāna in Pali), which means "meditation." In the image above one sees on the left the character 禪 in Japanese calligraphy and on the right an ensō, or Zen circle. In Japan the drawing of such a circle is considered a high art, the expression of a moment of enlightenment by the Zen master calligrapher. The tradition known as Chan Buddhism in China, and Zen Buddhism in Japan, brings together Mahāyāna Buddhism and Daoism. This confluence of Buddhism and Daoism in Zen is most obvious in the Chinese script on the left which reads: "The heart-mind (xin 心) is the buddha (佛), the buddha (佛) is the path (dao 道), the path (dao 道) is meditation (chan 禪)." The line is from a text called the Bloodstream Sermon attributed to the legendary Bodhidharma. An Indian meditation master, Bodhidharma had come to China around 520 CE and in time would come to be regarded as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism. In Bodhidharma’s Bloodstream Introduction to Asian Philosophy Zen Buddhism Sermon (in the Chan Buddhism online selections) it is evident that Bodhidharma had absorbed something of Daoism after he came to China. The Mahāyāna Buddhist teachings that are most evident in Bodhidharma’s text are the teachings of emptiness (Śūnyatā) from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras as well as the notion of the buddha-nature (dharmakāya) that is part of the Mahāyāna teaching of the three bodies (trikāya) of the Buddha. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

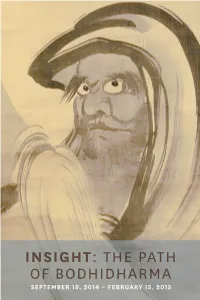

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

ACTAS 2013. Cubierta.Qxd (Page 1)

HR Budismo en España: historia y presente resulta un libro 3 Francisco Díez de Velasco complementario del titulado Budismo en España: historia, visibilización e implantación, que se publicó en su primera edición en 2013 y en una segunda edición puesta al día en formato e-book en 2018. Desarrolla y ahonda en algunos aspectos de la historia y de la implantación del budismo en nuestro país y es el resultado de una investigación llevada a Budismo en España: cabo desde hace tres lustros por el autor, Francisco Díez de Velasco, profesor de Historia de las Religiones en la Univer- sidad de La Laguna. historia y presente a y presente ri Histo España: n e mo s Budi , Velasco de ez Dí cisco n Fra Francisco Díez de Velasco BUDISMO EN ESPAÑA HISTORIA Y PRESENTE MADRID Primera edición 2020 Ediciones Clásicas S.A. garantiza un riguroso proceso de selección y evaluación de los trabajos que publica. La edición de este volumen forma parte del proyecto de investigación “Bases teóricas y metodológicas para el estudio de la diversidad religiosa y las minorías religiosas en España” (HAR2016-75173-P) del Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación de España, 2017-2020, desarrollado en la Universidad de La Laguna. Este trabajo utiliza los resultados del proyecto de investigación “Budismo en España”, inserto en el contrato de I + D entre la Fundación Pluralismo y Convivencia y la Universidad de La Laguna. (2010-2013) que produjo como publicación principal el libro F. Diez de Velasco, Budismo en España: historia, visibilización e implantación, Madrid, Akal, 2013, 350 pp. (ISBN 978-84-460-3679-1) que ha tenido una segunda edición (en formato e-book) con puesta al día completa en 2018 en la misma editorial (ISBN 978-84-460-4593-9). -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

A Beginner's Guide to Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK As countless meditators have learned firsthand, meditation practice can positively transform the way we see and experience our lives. This practical, accessible guide to the fundamentals of Buddhist meditation introduces you to the practice, explains how it is approached in the main schools of Buddhism, and offers advice and inspiration from Buddhism’s most renowned and effective meditation teachers, including Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Sharon Salzberg, Norman Fischer, Ajahn Chah, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Sylvia Boorstein, Noah Levine, Judy Lief, and many others. Topics include how to build excitement and energy to start a meditation routine and keep it going, setting up a meditation space, working with and through boredom, what to look for when seeking others to meditate with, how to know when it’s time to try doing a formal meditation retreat, how to bring the practice “off the cushion” with walking meditation and other practices, and much more. ROD MEADE SPERRY is an editor and writer for the Shambhala Sun magazine. Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO Meditation Practical Advice and Inspiration from Contemporary Buddhist Teachers Edited by Rod Meade Sperry and the Editors of the Shambhala Sun SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2014 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Sun Cover art: André Slob Cover design: Liza Matthews All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.