An Energetic Example of Bidirectional Sino-Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Transmission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents

-1155 Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents Note: Chinese names are romanized according to the traditional Wade-Giles system. The pinyin romanization appears in parentheses. Chinese Names Japanese Names An Ch’ing-hsü (An Qingxu) An Keisho An Lu-shan (An Lushan) An Rokuzan Chang-an (Zhangan) Shoan Chang Chieh (Zhang Jie) Cho Kai Chang Liang (Zhang Liang) Cho Ryo Chang Wen-chien (Zhang Wenjian) Cho Bunken Chao (Zhao), King Sho-o Chao Kao (Zhao Gao) Cho Ko Ch’en Chen (Chen Zhen) Chin Shin Ch’eng (Cheng), King Sei-o Cheng Hsüan (Zheng Xuan) Tei Gen Ch’eng-kuan (Chengguan) Chokan Chia-hsiang ( Jiaxiang) Kajo Chia-shang ( Jiashang) Kasho Chi-cha ( Jizha) Kisatsu Chieh ( Jie), King Ketsu-o Chieh Tzu-sui ( Jie Zisui) Kai Shisui Chien-chen ( Jianzhen) Ganjin Chih-chou (Zhizhou) Chishu Chih-i (Zhiyi) Chigi z Chih Po (Zhi Bo) Chi Haku Chih-tsang (Zhizang) Chizo Chih-tu (Zhidu) Chido Chih-yen (Zhiyan) Chigon Chih-yüan (Zhiyuan) Shion Ch’i Li-chi (Qi Liji) Ki Riki Ching-hsi ( Jingxi) Keikei Ching K’o ( Jing Ko) Kei Ka Ch’ing-liang (Qingliang) Shoryo Ching-shuang ( Jingshuang) Kyoso Chin-kang-chih ( Jingangzhi) Kongochi 1155 -1156 APPENDIX D Ch’in-tsung (Qinzong), Emperor Kinso-tei Chi-tsang ( Jizang) Kichizo Chou (Zhou), King Chu-o Chuang (Zhuang), King So-o Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Soshi Chu Fa-lan (Zhu Falan) Jiku Horan Ch’ung-hua (Chonghua) Choka Ch’u Shan-hsin (Chu Shanxin) Cho Zenshin q Chu Tao-sheng (Zhu Daosheng) Jiku Dosho Fa-ch’üan (Faquan) Hassen Fan K’uai (Fan Kuai) Han Kai y Fan Yü-ch’i (Fan Yuqi) Han Yoki Fa-pao -

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D

issn 0304-1042 Japanese Journal of Religious Studies volume 47, no. 1 2020 articles 1 Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan Matthew D. McMullen 11 Buddhist Temple Networks in Medieval Japan Daigoji, Mt. Kōya, and the Miwa Lineage Anna Andreeva 43 The Mountain as Mandala Kūkai’s Founding of Mt. Kōya Ethan Bushelle 85 The Doctrinal Origins of Embryology in the Shingon School Kameyama Takahiko 103 “Deviant Teachings” The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism Gaétan Rappo 135 Nenbutsu Orthodoxies in Medieval Japan Aaron P. Proffitt 161 The Making of an Esoteric Deity Sannō Discourse in the Keiran shūyōshū Yeonjoo Park reviews 177 Gaétan Rappo, Rhétoriques de l’hérésie dans le Japon médiéval et moderne. Le moine Monkan (1278–1357) et sa réputation posthume Steven Trenson 183 Anna Andreeva, Assembling Shinto: Buddhist Approaches to Kami Worship in Medieval Japan Or Porath 187 Contributors Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47/1: 1–10 © 2020 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.47.1.2020.1-10 Matthew D. McMullen Editor’s Introduction Esoteric Buddhist Traditions in Medieval Japan he term “esoteric Buddhism” (mikkyō 密教) tends to invoke images often considered obscene to a modern audience. Such popular impres- sions may include artworks insinuating copulation between wrathful Tdeities that portend to convey a profound and hidden meaning, or mysterious rites involving sexual symbolism and the summoning of otherworldly powers to execute acts of violence on behalf of a patron. Similar to tantric Buddhism elsewhere in Asia, many of the popular representations of such imagery can be dismissed as modern interpretations and constructs (White 2000, 4–5; Wede- meyer 2013, 18–36). -

Esoteric, Chan and Vinaya Ties in Tang Buddhism the Ordination Platform of the Huishan Monastery on Mount Song in the Religious Policy of Emperor Daizong

Esoteric, Chan and vinaya ties in Tang Buddhism The ordination platform of the Huishan monastery on Mount Song in the religious policy of Emperor Daizong Abstract This paper explores the reconstruction of the ordination platform in the Huishan monastery 會 善寺 on Mount Song in 767 in the context of the reinforcement of pro-Buddhist policies at the court of Emperor Daizong 代宗 (r. 762–779). The vinaya monks and state officials who engaged in this platform’s reconstruction are identified as associates of two prominent monastic figures: Amoghavajra (Bukong jin’gang 不空金剛; 704–774), an Esoteric leader at the imperial court; and Songshan Puji 嵩山普寂 (651–739), regarded as the seventh patriarch in the Northern Chan tradition. The key roles played by disciples of these two masters in the reconstruction of the Huishan platform attest to significant congruence in ritual practices between proponents of the Esoteric and Chan groups in Tang dynasty China, primarily in the areas of precept conferral and monastic ordination. Keywords Mount Song, Huishan monastery, Northern Chan, Esoteric Buddhism, vinaya, precept conferral Introduction During the Tang dynasty, the reign of Emperor Daizong 代宗 (r. 762–779) was second only to the reign of Empress Wu Zetian 武則天 (r. 690–705) in terms of imperial patronage of Buddhism. Daizong assumed the role of universal Buddhist monarch (cakravartin) and granted the Buddhist saṅgha and its foremost leader Amoghavajra (Ch. Bukong jin’gang 不空金剛; 704–774) an unprecedented amount of power.1 In 767, at the start of a new era that Daizong named Dali 大曆 (Grand Reign), many large-scale Buddhist projects were realized under the 1 Amoghavajra, an Esoteric master of allegedly Sogdian origin, became a paramount Buddhist leader at the imperial court during a period of highly militarized political turbulence in the territorial centre of the Tang Empire following the rebellion of General An Lushan 安祿山 (703–757) in 755. -

Sayyids and Shiʽi Islam in Pakistan

Legalised Pedigrees: Sayyids and Shiʽi Islam in Pakistan SIMON WOLFGANG FUCHS Abstract This article draws on a wide range of Shiʽi periodicals and monographs from the s until the pre- sent day to investigate debates on the status of Sayyids in Pakistan. I argue that the discussion by reform- ist and traditionalist Shiʽi scholars (ʽulama) and popular preachers has remained remarkably stable over this time period. Both ‘camps’ have avoided talking about any theological or miracle-working role of the Prophet’s kin. This phenomenon is remarkable, given the fact that Sayyids share their pedigree with the Shiʽi Imams, who are credited with superhuman qualities. Instead, Shiʽi reformists and traditionalists have discussed Sayyids predominantly as a specific legal category. They are merely entitled to a distinct treatment as far as their claims to charity, patterns of marriage, and deference in daily life is concerned. I hold that this reductionist and largely legalising reading of Sayyids has to do with the intense competition over religious authority in post-Partition Pakistan. For both traditionalist and reformist Shiʽi authors, ʽulama, and preachers, there was no room to acknowledge Sayyids as potential further competitors in their efforts to convince the Shiʽi public about the proper ‘orthodoxy’ of their specific views. Keywords: status of Sayyids; religious authority in post-Partition Pakistan; ahl al-bait; Shiʻi Islam Bashir Husain Najafi is an oddity. Today’s most prominent Pakistani Shiʽi scholar is counted among Najaf’s four leading Grand Ayatollahs.1 Yet, when he left Pakistan for Iraq in in order to pursue higher religious education, the deck was heavily stacked against him. -

Matthew Fox and the Cosmic Christ

Matthew Fox and the Cosmic Christ ~GARETBREARLEY The myth of matricide Matthew Fox, an American Dominican, is a prolific and controversial author, whose 'creation spirituality' is gaining wide influence within both Roman Catholic and Anglican churches and retreat centres. To review his recent book, The Coming of the Cosmic Christ: The Healing of Mother Earth and the Birth of a Global Renaissance (Harper & Row, San Francisco 1988) is an even more complex task than reviewing his earlier writings, for it is somewhat like a hologram; its beginning, entitled: 'Prologue: A Dream and a VISion', already contains its end; each segment of the text is interdependent on the rest and, in a sense, contains the whole. Rather than developing thought and argument in logical progression, the book represents shafts of light thrown from different perspectives on one central image or myth. For the first time Fox has constructea an all-embracing myth which he believes is capable of explaining the totality of contemporary reality. He then demonstrates a new ethic, derived from that myth, and finally demands that an utterly new reality be formed on the basis of his central myth and its ethic. The dominant myth is that of matricide. Fox accuses traditional Christi anity - and therefore Western culture - of being matricidal. In earlier writings he had already radically condemned Christian orthodoxy. While claiming to restore the Hebrew roots of Christianity, Fox had in fact rejected both the God of Israel and traditional prayer as 'useless' and denied both Old and New Testaments as sources of revelation.1 In The Coming of the Cosmic Christ Fox is even more radical. -

Explored Countless Lab- Oratories, Interviewed a Myriad of Scientists, and Prepared Thousands of News Releases, Feature Articles, Web Sites, and Multimedia Packages

Explaining Research This page intentionally left blank Explaining Research How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work Dennis Meredith 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Dennis Meredith Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meredith, Dennis. Explaining research : how to reach key audiences to advance your work / Dennis Meredith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-973205-0 (pbk.) 1. Communication in science. 2. Research. I. Title. Q223.M399 2010 507.2–dc22 2009031328 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my mother, Mary Gurvis Meredith. She gave me the words. This page intentionally left blank You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother. -

Happy Purim! RABBANIT SHANI TARAGIN on Why Purim Is the Most Zionistic Holiday

ADAR SHEINI 5779 MARCH 2019 TORAT ERETZ YISRAEL • PUBLISHED IN SHUSHAN • DISTRIBUTED AROUND THE WORLD ISRAEL EDITION RABBI BEREL WEIN פורים שמח! living our own purim story PAGE 24 Happy Purim! RABBANIT SHANI TARAGIN on why purim is the most zionistic holiday PAGE 5 RABBI JONATHAN SACKS invites us to be alert to G-d's messages PAGE 14 SIVAN RAHAV-MEIR with advice for a noisy world PAGE 23 RABBI CHAIM NAVON analyzes binge relationships PAGE 22 RABBANIT YEMIMA MIZRACHI with some magical moments for women this issue is dedicated in loving memory of PAGE 21 professor cyril domb by his wife and children Torat HaMizrachi HITLER, HAMAN & HAMAS A Parashat Zachor and Purim Primer bsolute evil has existed for minute. Thousands of years later, Individuals and societies possess both millennia. It constitutes a Hitler declared the same intentions. the passion for altruistic good and single-minded, systematic Tragically, he succeeded in murdering the impulse for self-destructive evil. focusA to destroy all good in the world. one third of the Jewish people, and Israel's mission is chiefly the former; According to Torah tradition, it has a if not for the hand of Providence Amalek's the latter. name. Amalek. The Torah commands guiding the actions of the Allied It was not by chance that Amalek was us to always remember and never Forces, he would have gone much 1 the first nation to attack Israel, as forget what Amalek represents. further. Unstopped and unchecked, this type of evil would, G-d forbid, soon as we came out of Egypt. -

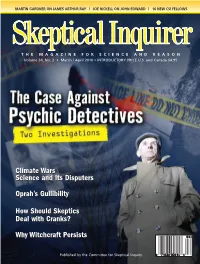

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

¬¬Journal of Buddhist Ethics

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: How Many Bodies Does It Take to Make a Buddha? Dividing the Trikāya among Founders of Japanese Buddhism Author(s): Victor Forte Source:Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XXIV (2020), pp. 35-60 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan- studies-review/journal-archive/volume-xxiv-2020/forte-victor- how-many-bodies.pdf ______________________________________________________________ HOW MANY BODIES DOES IT TAKE TO MAKE A BUDDHA? DIVIDING THE TRIKĀYA AMONG FOUNDERS OF JAPANESE BUDDHISM Victor Forte Albright College Introduction Much of modern scholarship concerned with the historical emer- gence of sectarianism in medieval Japanese Buddhism has sought to deline- ate the key features of philosophy and praxis instituted by founders in order to illuminate critical differences between each movement. One of the most influential early proposed delineations was “single practice theory,” ikkō senju riron 一向専修理論 originating from Japanese scholars like Jikō Hazama 慈弘硲 and Yoshiro Tamura 芳朗田村.1 This argument focused on the founders of the new Kamakura schools during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries like Hōnen 法然, Shinran 親鸞, Dōgen 道元, and Nichiren 日蓮, claiming that each promoted a single Buddhist practice for the attainment of liberation at the exclusion of all other rival practices. In recent scholarship, however, single practice theory has been brought into question.2 As an alternative method of delineation, this study proposes the examination of how three major premod- ern Japanese founders (Kūkai 空海, Shinran, and Dōgen) employed the late Indian Mahāyāna notion of the three bodies of the Buddha (Skt. trikāya, Jp. sanshin 三身) by appropriating a single body of the Buddha in order to distin- guish each of their sectarian movements. -

Platonic Mysticism

CHAPTER ONE Platonic Mysticism n the introduction, we began with the etymology of the word I“mysticism,” which derives from mystes (μύστης), an initiate into the ancient Mysteries. Literally, it refers to “one who remains silent,” or to “that which is concealed,” referring one’s direct inner experi- ence of transcendence that cannot be fully expressed discursively, only alluded to. Of course, it is not clear what the Mysteries revealed; the Mystery revelations, as Walter Burkert suggested, may have been to a significant degree cosmological and magical.1 But it is clear that there is a related Platonic tradition that, while it begins with Plato’s dialogues, is most clearly expressed in Plotinus and is conveyed in condensed form into Christianity by Dionysius the Areopagite. Here, we will introduce the Platonic nature of mysticism. That we focus on this current of mysticism originating with Plato and Platonism and feeding into Christianity should not be understood as suggesting that there is no mysticism in other tradi- tions. Rather, by focusing on Christian mysticism, we will see much more clearly what is meant by the term “mysticism,” and because we are concentrating on a particular tradition, we will be able to recog- nize whether and to what extent similar currents are to be found in other religious traditions. At the same time, to understand Christian mysticism, we must begin with Platonism, because the Platonic tra- dition provides the metaphysical context for understanding its latest expression in Christian mysticism. Plato himself is, of course, a sophisticated author of fiction who puts nearly all of what he wrote into the form of literary dialogues 9 © 2017 Arthur Versluis 10 / Platonic Mysticism between various characters.