Abstracts # DIJ-Mono 65 Blecken ENGLISH.Fm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan

The Numata Conference on Buddhist Studies: Violence, Nonviolence, and Japanese Religions: Past, Present, and Future. University of Hawaii, March 2014. Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan Mickey Adolphson University of Alberta 2014 What is religious violence and why is it relevant to us? This may seem like an odd question, for 20–21, surely we can easily identify it, especially considering the events of 9/11 and other instances of violence in the name of religion over the past decade or so? Of course, it is relevant not just permission March because of acts done in the name of religion but also because many observers find violence noa, involving religious followers or justified by religious ideologies especially disturbing. But such a ā author's M notion is based on an overall assumption that religions are, or should be, inherently peaceful and at the harmonious, and on the modern Western ideal of a separation of religion and politics. As one Future scholar opined, religious ideologies are particularly dangerous since they are “a powerful and Hawai‘i without resource to mobilize individuals and groups to do violence (whether physical or ideological of violence) against modern states and political ideologies.”1 But are such assumptions tenable? Is a quote Present, determination toward self-sacrifice, often exemplified by suicide bombers, a unique aspect of not violence motivated by religious doctrines? In order to understand the concept of “religious do Past, University violence,” we must ask ourselves what it is that sets it apart from other violence. In this essay, I the and at will discuss the notion of religious violence in the premodern Japanese setting by looking at a 2 paper Religions: number of incidents involving Buddhist temples. -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

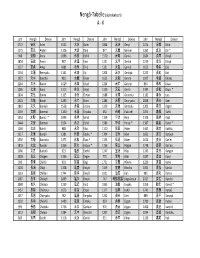

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies English Selection

Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies English Selection 3 | 2014 On The Tale of Genji: Narrative, Poetics, Historical Context From the Kagerō no nikki to the Genji monogatari Du Kagerō no nikki au Genji monogatari Jacqueline Pigeot Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/cjs/687 DOI: 10.4000/cjs.687 ISSN: 2268-1744 Publisher INALCO Electronic reference Jacqueline Pigeot, “From the Kagerō no nikki to the Genji monogatari”, Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies [Online], 3 | 2014, Online since 12 October 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cjs/687 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/cjs.687 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Cipango - French Journal of Japanese Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. From the Kagerō no nikki to the Genji monogatari 1 From the Kagerō no nikki to the Genji monogatari Du Kagerō no nikki au Genji monogatari Jacqueline Pigeot EDITOR'S NOTE Original release : Jacqueline PIGEOT, « Du Kagerō no nikki au Genji monogatari », Cipango, Hors-série, 2008, 69-87. Jacqueline PIGEOT, « Du Kagerō no nikki au Genji monogatari », Cipango [En ligne], Hors- série | 2008, mis en ligne le 24 février 2012. URL : http://cipango.revues.org/592 ; DOI : 10.4000/cipango.592 1 The scholarly community now concurs that the Genji monogatari is indebted to the Kagerō no nikki 蜻蛉日記 (The Kagerō Diary), the first extant work in Japanese prose written by a woman.1 2 The Kagerō author, known only as “the mother of Fujiwara no Michitsuna” 藤原道綱母, and Murasaki Shikibu are separated by a generation or two: the former was born in 936 and the latter around 970. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Fine Japanese and Korean Art I New York I September 11, 2019

Fine Japanese and Korean Art and Korean Fine Japanese I New York I September 11, 2019 I New York Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 11, 2019 Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York | Wednesday September 11, 2019, at 1pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit REGISTRATION www.bonhams.com/25575 Thursday September 5 Takako O’Grady IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm +1 (212) 461 6523 Please note that all customers, Friday September 6 Please note that bids should be [email protected] irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm summited no later than 24hrs with Bonhams, are required to Saturday September 7 prior to the sale. New bidders complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of Form in advance of the sale. The Sunday September 8 identity when submitting bids. form can be found at the back 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in of every catalogue and on our Monday September 9 your bid not being processed. website at www.bonhams.com 10am to 5pm and should be returned by email or Tuesday September 10 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS post to the specialist department 10am to 3pm AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE or to the bids department at Please email bids.us@bonhams. -

Edo: Art in Japan 1615-1868; Teaching Program

edo teach.qxd4 12/9/98 10:42 AM Page 1 Teaching Program Edo art in japan 1615 – 1868 national gallery of art, washington edo teach.qxd4 12/9/98 10:42 AM Page 2 The exhibition Edo: Art in Japan 1615 – 1868 is made possible by NTT Exhibition dates: 15 November 1998 through 15 February 1999 edo teach.qxd4 12/9/98 10:42 AM Page 1 Edo Art in Japan 1615 – 1868 Teaching Program National Gallery of Art, Washington edo teach.qxd4 12/9/98 10:42 AM Page 2 acknowledgments notes to the reader This teaching program was written for the The Japanese government has designated education division by Christine Guth, an inde- numerous works of art as National Treasures, pendent scholar. Since receiving her Ph.D. in Important Cultural Properties, or Important Art Fine Arts from Harvard University in 1976, she Objects because of their artistic quality, historic has taught at institutions such as Harvard, value, and rarity. Several works with these des- Princeton, and the University of Pennsylvania. ignations are included in this publication. Her recent publications include Art, Tea, and Industry: Masuda Takashi and the Mitsui Circle Dimensions are in centimeters, followed by (Princeton, 1993) and Art of Edo Japan: The Artist inches in parentheses, height preceding width, and the City, 1615Ð1868 (New York, 1996). and width preceding depth. Concept development and teaching activities Cover: Watanabe Shik¿, Mount Yoshino, early by Anne Henderson, Heidi Hinish, and Barbara eighteenth century, detail from a pair of six- Moore. panel screens; ink, color, and gold on paper, Private Collection, Kyoto Thanks to Leo Kasun, Elisa Patterson, Ruth Perlin, Renata Sant’anna, Takahide Tsuchiya, Title page: Dish with radish and waves design, and Susan Witmer for their assistance with c. -

Japan and the Russian Federation

DGIV/EDU/HIST (2000)10 Activities for the Development and Consolidation of Democratic Stability (ADACS) Meeting of Experts on History Teaching –Japan and the Russian Federation Tokyo, Japan, 25 -27 October 2000 Proceedings Strasbourg Meeting of Experts on History Teaching – Japan and the Russian Federation Tokyo, Japan, 25 -27 October 2000 Proceedings The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................... 5 II. OFFICAL PRESENTATIONS................................................................... 7 III. PRESENTATIONS OF THE RUSSIAN EXPERTS ................................. 13 Dr V. BATSYN........................................................................................... 13 Dr S. GOLUBEV........................................................................................ 18 Dr O. STRELOVA...................................................................................... 23 Dr T.N. ROMANCHENKO........................................................................ 35 IV.PRESENTATIONS OF THE JAPANESE EXPERTS............................... 42 Professor Y. TORIUMI............................................................................... 42 Professor M. MATSUMURA..................................................................... 50 Professor K. TAMURA............................................................................. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Download the Japan Style Sheet, 3Rd Edition

JAPAN STYLE SHEET JAPAN STYLE SHEET THIRD EDITION The SWET Guide for Writers, Editors, and Translators SOCIETY OF WRITERS, EDITORS, AND TRANSLATORS www.swet.jp Published by Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators 1-1-1-609 Iwado-kita, Komae-shi, Tokyo 201-0004 Japan For correspondence, updates, and further information about this publication, visit www.japanstylesheet.com Cover calligraphy by Linda Thurston, third edition design by Ikeda Satoe Originally published as Japan Style Sheet in Tokyo, Japan, 1983; revised edition published by Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, CA, 1998 © 1983, 1998, 2018 Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher Printed in Japan Contents Preface to the Third Edition 9 Getting Oriented 11 Transliterating Japanese 15 Romanization Systems 16 Hepburn System 16 Kunrei System 16 Nippon System 16 Common Variants 17 Long Vowels 18 Macrons: Long Marks 18 Arguments in Favor of Macrons 19 Arguments against Macrons 20 Inputting Macrons in Manuscript Files 20 Other Long-Vowel Markers 22 The Circumflex 22 Doubled Letters 22 Oh, Oh 22 Macron Character Findability in Web Documents 23 N or M: Shinbun or Shimbun? 24 The N School 24 The M School 24 Exceptions 25 Place Names 25 Company Names 25 6 C ONTENTS Apostrophes 26 When to Use the Apostrophe 26 When Not to Use the Apostrophe 27 When There Are Two Adjacent Vowels 27 Hyphens 28 In Common Nouns and Compounds 28 In Personal Names 29 In Place Names 30 Vernacular Style -

Lomi, B. (2019). Ox-Bezoars and the Materiality of Heian-Period Therapeutics

Lomi, B. (2019). Ox-Bezoars and the Materiality of Heian-period Therapeutics. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 45(2), 227-268. [1]. https://doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.45.2.2018.227-268 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC Link to published version (if available): 10.18874/jjrs.45.2.2018.227-268 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture at https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/4677 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 45/2: 227–268 © 2018 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture dx.doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.45.2.2018.227-268 Benedetta Lomi Ox Bezoars and the Materiality of Heian-period Therapeutics This article addresses the issue of sacred materiality by exploring the produc- tion, extraction, and circulation of ox bezoars in the late Heian period. Bezoar, a highly-valued concretion found in the stomachs of bovines, was renowned for its healing properties and employed by Daigoji ritualists as part of safe childbirth practices. Although the bezoar was empowered by Buddhist monks before its therapeutic applications, I suggest that its efficacy is only in part the result of empowerment.