Shinto Ritual Building Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

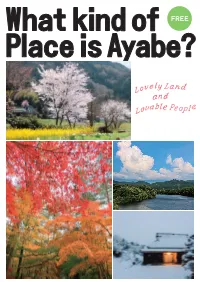

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

By \O-Icniro Hakomori,Hiroyuki Nagahara,Herbert Plutschow. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History,Textile Series, No. 6. L

BOOK REVIEWS 331 ing and accompaniment (“Hagoromo”),and two pieces from the classical shakuhachi reper tory (“Kokd” and “Tsuru no sugomori”)perhaps played by Higuchi Taizan. Recordings such as the ones reissued on this CD are perhaps not of sufficiently high quality to allow one to lie back in the easy chair and partake in sheer aesthetic delight, but for the scholars or other listeners who wish to make good use of their facility of imagination these wax cylinders are real treasures. The explanatory notes by Ingrid Fritsch, well known for her outstanding work on Japanese shakuhachi music and the various groups of Japanese blind musicians, are a model of what such work can be. The engineers, too, have done more than one might expect, providing faithful reproductions of antiquated sources that now stand a good chance of survival.A further publication of the Japan collection of Lachmann (1924—1925) and Schiinemann (1924) has been announced. An additional ten years of tech nological development no doubt meant far more then than it does now and I look forward to hearing what has so long remained tantalizing but out of reach. REFERENCES CITED G roemer, Gerald 1999 The Arts of the Gannin. Asian Folklore Studies, 53: 275-320. Yomigaeru Opp吹epee: 1900-nen Pari-banpal^u no Kawahami ichiza, CD, Toshiba EMI, TOCG 5432 (1997). Gerald GROEMER Yamanashi University Kofu, Japan Gonick, G loria Ganz. Matsuri! Japanese Festival Arts. With contributions by \o-icniro Hakomori,Hiroyuki Nagahara,Herbert Plutschow. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History,Textile Series, No. 6. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History,2003. -

The Making of an American Shinto Community

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SHINTO COMMUNITY By SARAH SPAID ISHIDA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2007 Sarah Spaid Ishida 2 To my brother, Travis 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people assisted in the production of this project. I would like to express my thanks to the many wonderful professors who I have learned from both at Wittenberg University and at the University of Florida, specifically the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Mario Poceski and Dr. Jason Neelis. For their time, advice and assistance, I would like to thank Dr. Travis Smith, Dr. Manuel Vásquez, Eleanor Finnegan, and Phillip Green. I would also like to thank Annie Newman for her continued help and efforts, David Hickey who assisted me in my research, and Paul Gomes III of the University of Hawai’i for volunteering his research to me. Additionally I want to thank all of my friends at the University of Florida and my husband, Kyohei, for their companionship, understanding, and late-night counseling. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to the Shinto community of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Reverend Koichi Barrish. Without them, this would not have been possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................7 -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

The Japanese House

THE JAPANESE HOUSE Or, why the Western architect has difficulties to understand it. Harmonious space and the Archetype of polar space The traditional Japanese dwelling and the Western concept of 'general human needs' - a comparative view in the framework of cultural anthropology By Nold Egenter Introduction Any western architect who intends to design a house or an apartment basically will start from assumption of 'the primary human needs' of the future inhabitants. Essentially three components define our western concept of primary needs. First there are physical parameters, the measurements of the human body. Neufert has presented these aspects in great detail. Further there are physiological conditions, e.g. the need for protection of various kinds: sufficient light and air, hygiene etc. Finally, a standardised behaviour is assumed, requiring sufficient space for moving, working, eating, ablutions, leisure etc. In this context space is considered as a three dimensional, basically homogeneous and neutral condition. Depending on the given conditions, the program of walls and openings, installations and surfaces for movement, fittings and functional places designed by the architect, will be set relatively freely into this homogeneously conceived space. Several years ago a study of the European Community concluded that the Japanese live in "rabbit cages". The study was based essentially on statistical research which showed that the average dwelling space for a family in urban agglomerations hardly amounts to 40 square meters. Great astonishment! -

Alma M. Karlin's Visits to Temples and Shrines in Japan

ALMA M. KARLIN’S VISITS TO TEMPLES AND SHRINES IN JAPAN Chikako Shigemori Bučar Introduction Alma M. Karlin (1889-1950), born in Celje, went on a journey around the world between 1919 and 1928, and stayed in Japan for a lit- tle more than a year, from June 1922 to July 1923. There is a large col- lection of postcards from her journey archived in the Regional Museum of Celje. Among them are quite a number of postcards from Japan (528 pieces), and among these, about 100 of temples and shrines, including tombs of emperors and other historical persons - i.e., postcards related to religions and folk traditions of Japan. Karlin almost always wrote on the reverse of these postcards some lines of explanation about each picture in German. On the other hand, the Japanese part of her trav- elogue is very short, only about 40 pages of 700. (Einsame Weltreise / Im Banne der Südsee, both published in Germany in 1930). In order to understand Alma Karlin’s observation and interpretation of matters related to religions in Japan and beliefs of Japanese people, we depend on her memos on the postcards and her rather subjective impressions in her travelogue. This paper presents facts on the religious sights which Karlin is thought to have visited, and an analysis of Karlin’s understand- ing and interpretation of the Japanese religious life based on her memos on the postcards and the Japanese part of her travelogue. In the following section, Alma Karlin and her journey around the world are briefly presented, with a specific focus on the year of her stay in Japan, 1922-1923. -

Conservation of Living Religious Heritage ICCROM Conservation Studies 3

ICCROM COnseRvatIOn studIes 3 Conservation of Living Religious Heritage ICCROM COnseRvatIOn studIes 3 Conservation of Living Religious Heritage Papers from the ICCRoM 2003 forum on Living Religious Heritage: conserving the sacred Editors Herb Stovel, Nicholas Stanley-Price, Robert Killick ISBN 92-9077-189-5 © 2005 ICCROM International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele, 13 00153 Rome, Italy www.iccrom.org Designed by Maxtudio, Rome Printed by Ugo Quintily S.p.A. Contents Preface v NICHOLAS STANLEY-PRICE introduction 1 HERB STOVEL Conserving built heritage in Maori communities 12 1 DEAN WHITING Christiansfeld: a religious heritage alive and well. TwenTy-firsT cenTury influences on a laTe eighTeenTh- 2 early nineTeenTh cenTury Moravian seTTleMenT in DenMark 19 JØRGEN BØYTLER the past is in the present 3 perspecTives in caring for BuDDhisT heriTage siTes in sri lanka 31 GAMINI WIJESURIYA the ise shrine and the Gion Festival case sTuDies on The values anD auThenTiciTy of Japanese 4 inTangiBle living religious heriTage 44 NOBUKO INABA A living religious shrine under siege The nJelele shrine/king Mzilikazi’s grave anD conflicTing 5 DeManDs on The MaTopo hills area of ziMBaBwe 58 PATHISA NYATHI AND CHIEF BIDI NDIWENI ISBN 92-9077-189-5 the challenges in reconciling the requirements of faith and © 2005 ICCROM 6 conservation in Mount Athos 67 International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property JANIS CHATZIGOGAS Via di San Michele, 13 00153 Popular worship of the Most Holy trinity of Vallepietra, Rome, Italy 7 central italy The TransforMaTion of TraDiTion anD The safeguarDing www.iccrom.org of iMMaTerial culTural heriTage 74 PAOLA ELISABETTA SIMEONI Designed by Maxtudio, Rome Printed by Ugo Quintily S.p.A. -

Thesis Title: Shimenawa: Weaving Traditions with Modernity – Interdisciplinary Research on the Cultural History of Japanese Sacred Rope

Thesis Title: Shimenawa: Weaving Traditions with Modernity – Interdisciplinary Research on the Cultural History of Japanese Sacred Rope Shan Zeng, Class of 2019 I have not received or given unauthorized assistance. 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my greatest appreciation to my advisors Professor Morrison and Professor Laursen, as well as Professor Sassin and Professor Garrison, without whose support this project would not have come to fruition. I also want to thank my Japanese instructors Hayasaka sensei, Takahashi sensei, and Cavanaugh sensei, whose exceptional language classes gave me the courage and competence to conduct fieldwork in Japanese. My thanks go to Professor Milutin for patiently sifting through emaki and ancient Japanese poems with me and to Professor Ortegren for sharing her experiences on ethnographic fieldwork. I would also like to thank my first-year advisor Professor Sheridan, and all the other faculty and staff from the Middlebury Department of Religion and Department of History of Art and Architecture for their valuable feedback and support. I extend my special thanks to the following people, who not only graciously accepted my interviews but showed me the incredible hospitality, kindness and patience of the Japanese people: Orihashi san and her fellow colleagues at Nawawaseya, Shiga san and his family, Nagata san of Izumo Oyashiro, Nasu san and his colleagues at Oshimenawa Sousakukan, Matsumoto San, Yamagawa san and his father at Kyoto, Koimizu san, Takashi san, Kubishiro and his workshop, and Oda san. My appreciation goes to all the other people who have helped me one way or another during my stay in Japan, from providing me food and shelter to helping me find my lost camera. -

Download The

REVIEW OF REVIEWS Nihon minzokugaku (Japanese Folklore Science), V ol.V, No. 2 (August 1958) Kojima Yukiyoshi: On the Belief in Kompira. Kompira is a guardian-god of fishermen and sailors. The name Kompira is a foreign import, the belief in the god is how ever part of the oldest religion of the people, from Izu Oshima in the East on down to the Goto Islands of Nagasaki Prefecture in the West. Folk tradition has it that the god stays at home and takes care of the houses and villages when all other gods start on a journey in October. During this time a festival is celebrated in his honor at which he is frequently worshipped as god of agriculture. Whether the god’s function as caretaker is part of his original nature or a later acquisition we can only guess. Ushio Michio: The Form of Oracles in Kagura,Sacred Shinto Music. In the kagura in honor of the kitchen-god Kojin in Okayama Prefecture people ask for an oracle for every seven or every thirteen years. In order to obtain the divine message they pile up brushwood around the sanctuary (shinden) of the god and set it afire. Ritual straw-ropes are hung along the boundary of the shrine precincts. Then two shrine ministers, swinging pine torches, start a wild dance, shouting goya, goya and beating one another with stones. One of them is supposed to be Kojin, the other one a man. Kojin tries to put the man to flight and a frantic scene develops under the eyes of the onlooking crowd through which the man dashes and gives up. -

Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender

Myths of Hakko Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Teshima, Taeko Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 21:55:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194943 MYTHS OF HAKKŌ ICHIU: NATIONALISM, LIMINALITY, AND GENDER IN OFFICIAL CEREMONIES OF MODERN JAPAN by Taeko Teshima ______________________ Copyright © Taeko Teshima 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Taeko Teshima entitled Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Barbara A. Babcock _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Philip Gabriel _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Susan Hardy Aiken Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement.