Labrador and the Dictionary of Newfoundland English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration in Rural Newfoundland: Individual and Community Change Willow Jackson Anderson

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Communication ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2012 Immigration in rural Newfoundland: Individual and community change Willow Jackson Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds Recommended Citation Jackson Anderson, Willow. "Immigration in rural Newfoundland: Individual and community change." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds/30 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Willow Jackson Anderson Candidate Communication and Journalism Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Karen A. Foss, Chairperson John G. Oeztel Pam Lutgen-Sandvik Magdalena Avila i IMMIGRATION IN RURAL NEWFOUNDLAND: INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNITY CHANGE BY WILLOW JACKSON ANDERSON B.A. Political Science and History, Mount Allison University, 1996 M.A. Conflict Resolution, University of Bradford, 1999 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Communication The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2012 ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work to two of my nieces, (my muses), Kaia and Madeline Jackson-Perez and their Uncle Dave. Kaia and Madeline: Thank you for the fun sleepovers, dramatic dance routines, and loads of (fun) book reading. May you flourish and grow and always be confident in your place. Dave, I would not have survived this process unscathed without you. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C). -

Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:10 p.m. Ethnologies “Making Cool Things Hot Again” Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best Hommage à Peter Narváez Article abstract In Honour of Peter Narváez This article critically examines instances of blackface in Newfoundland Volume 30, Number 2, 2008 Christmas mummering. Following Peter Narváez’s call for analysis of expressive culture from folklore and cultural studies approaches, I explore the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019953ar similarities between these two cultural phenomena. I see them as attempts to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar work out racial and class tensions among the underclasses dwelling in burgeoning seaport towns along the North American seaboard that were intimately connected, at that time, through heavily-trafficked shipping routes. I See table of contents offer a reanalysis of the tradition that goes beyond unconscious, symbolic ritualism to one that examines mummering in a historical context. As such, I present evidence which troubles widely held understandings of Christmas Publisher(s) mummering as an English-derived calendar custom. Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Best, K. (2008). “Making Cool Things Hot Again”: Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering. Ethnologies, 30(2), 215–248. https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Newfoundland English

Izaro Zalacain Mendia Degree in English Studies 2019-2020 NEWFOUNDLAND ENGLISH Supervisor: Miren Alazne Landa Departamento de Filología Inglesa, Alemana y de Traducción e Interpretación Área de Filología Inglesa Abstract The English language has undergone many variations, leaving uncountable dialects in every nook and cranny of the world. Located at the north-east of Canada, the island of Newfoundland presents one of those dialects. However, within the many varieties the English language features, Newfoundland English (NE) remains as one of the less researched dialects in North America. The aim of this paper is to provide a characterisation of NE. In order to do so, this paper focuses on research questions on the origins of the dialect, potential variation within NE, the languages it has been in contact with, its particular linguistic features and the role of linguistic distinction in the Newfoundlander identity. Thus, in this paper I firstly assess the origins of NE, which are documented to mainly derive from West Country, England, and south-eastern Ireland, and I also provide an overview of the main historical events that have influenced the language. Secondly, I show the linguistic variation NE features, thus displaying the multiple dialectal areas that are found in the island. Furthermore, I discuss the different languages that have been in contact with the variety, namely, Irish Gaelic and Micmac, among others. Thirdly, I present a variety of linguistic features of NE -both phonetic and morphosyntactic- that distinguish the dialect from the rest of North American varieties, including Canadian English. Finally, I tackle the issue of language and identity and uncover a number of innovations and purposeful uses of certain features that the islanders show in their speech for the sake of identity marking. -

Performance and Perceptions of Authenticity in Irish-Newfoundland English

They do be anxious about their speech: Performance and Perceptions of Authenticity in Irish-Newfoundland English MICHAEL COLLINS University of Toronto [email protected] Introduction 'This failure to produce, on command, this relic of our dear culture . I’ve been accused (more than once) of failing on purpose. There’s a sense that if I grew up there, it’s obviously something I should be able to perform, and to fail to do so demonstrates some guardedness or falseness . to fail in this performative aspect of our culture automatically questions the legitimacy of one’s (in this case, my own) cultural attachment.' (Butler 2011) 'Krystin Pellerin is from Newfoundland. So why make her use an accent? Just talk like normal fucking human beings' (bluekaffee.com 2010). NEWFOUNDLAND ENGLISH PRESENTS MANY CURRENT SPEAKERS WITH A DILEMMA. After 1949, when Newfoundland became part of Canada, standard Canadian English has become an implicit and explicit standard. It is heard in broadcast media and from speakers who have moved to Newfoundland from other parts of Canada, often to fill positions of prominence and power. However, the dilemma is not of a unitary non-standard dialect struggling to be preserved or respected. Instead, Newfoundland demonstrates a variety of non-standard dialects of English, existing in a state of both tension and partial fusion. Sandra Clarke describes Newfoundland English’s 'considerable range of linguistic variation' as not merely a result of 'settlement history and ethnicity' but also reflecting 'such social factors as age or rural versus urban residence–not to mention gender and socio-economic background' (Clarke 2010, 16). -

3. Naskapi Women: Words, Narratives, and Knowledge

chapter three Naskapi Women Words, Narratives, and Knowledge Carole Lévesque, Denise Geoffroy, and Geneviève Polèse By sharing their stories and knowledge, Naskapi women have played a key role in the reconstruction of the cultural and ecological heritage of their people. The Naskapi, who live in the subarctic region of the province of Québec, today represent about nine hundred people, most of whom reside in the village of Kawawachikamach, located about fifteen kilometres from the former mining town of Schefferville, along the 55th parallel (see map 3.1). The first written reports of the Naskapi date from the late eighteenth century. It appears that, at the time of the Europeans’ arrival, the peoples to whom these reports refer did not form a single, integrated group rather they were several groups of hunters who ranged across the northern portion of the Québec Labrador peninsula (Lévesque, Rains, and de Juriew 2001). The evidence suggests that these were families or groups of hunters of Innu origin who, sometime around the mid-eighteenth century, had apparently migrated to the hinterland of the subarctic region from the North Shore of the St. Lawrence (where several Innu bands had settled). Initially few in number, the Naskapi are said to have comprised about three hundred people around 1830 (Lévesque et al. 2001). 59 doi:10.15215/aupress/9781771990417.01 Ungava Bay Québec Fort Chimo Fort McKenzie Kawawachikamach Newfoundland and Labrador Québec Map 3.1 Location of the Naskapi village of Kawawachikamach, northern Québec. Source: Laboratoire d’analyse spatiale et d’économie urbaine et régionale, Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Montréal. -

2010 Report on the Status of B.C First Nations Languages

Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010 Tsilhqot’in Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Gitsenimx̱ Nisg̱a’a Hul’q’umi’num Nsyilxcən St̓át̓imcets Nedut’en Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Nłeʔkepmxcín Halq’eméylem Kwak̓wala Secwepemctsin Lekwungen Wetsuwet’en Nuučaan̓uɫ Hən̓q̓əm̓inəm̓ enaksialak̓ala SENĆOŦEN Tāłtān Malchosen Semiahmoo T’Sou-ke Dene K’e Nuxalk X̱aaydaa Kil Sm̓algya̱x Hailhzaqvla Éy7á7juuthem Ktunaxa Tse’khene Danezāgé’ X̱aad Kil Diitiidʔaatx̣ Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim “…I was beginning to fear that our language was slowly She shashishalhem Łingít disappearing, especially as each Elder is put into the ground.” Nicola Clara Camille, secwepemctsin speaker Pəntl’áč Wetalh Ski:xs Oowekyala prepared by the First peoples’ heritage, language and Culture CounCil The First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council (First We sincerely thank the B.C. First Nations language revitalization Peoples’ Council) is a provincial Crown Corporation dedicated to First experts for the expertise and input they provided. Nations languages, arts and culture. Since its formation in 1990, the Dr. Lorna Williams First Peoples’ Council has distributed over $21.5 million to communi- Mandy Na’zinek Jimmie, M.A. ties to fund arts, language and culture projects. Maxine Baptiste, M.A. Dr. Ewa Czaykowski-Higgins The Board and Advisory Committee of the First Peoples’ Council consist of First Nations community representatives from across B.C. We are grateful to the three language communities featured in our case studies that provided us with information on the exceptional The First Peoples’ Council Mandate, as laid out in the First Peoples’ language revitalization work they are doing. Council Act, is to: Nuučaan̓uɫ (Barclay Dialect) • Preserve, restore and enhance First Nations’ heritage, language Halq’emeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) and culture. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

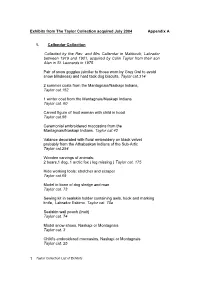

1 Exhibits from the Taylor Collection Acquired July 2004 Appendix a 1

Exhibits from The Taylor Collection acquired July 2004 Appendix A 1. Callendar Collection Collected by the Rev. and Mrs Callendar in Makkovik, Labrador between 1919 and 1921, acquired by Colin Taylor from their son Alan in St. Leonards in 1975 Pair of snow goggles (similar to those worn by Grey Owl to avoid snow blindness) and hard tack dog biscuits, Taylor cat.314 2 summer coats from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.152 1 winter coat from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. 60 Carved figure of Inuit woman with child in hood Taylor cat.58 Ceremonial embroidered moccasins from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.42 Valance decorated with floral embroidery on black velvet probably from the Athabaskan Indians of the Sub-Artic Taylor cat.294 Wooden carvings of animals: 2 bears,1 dog, 1 arctic fox ( leg missing ) Taylor cat. 175 Hide working tools: stretcher and scraper Taylor cat.69 Model in bone of dog sledge and man Taylor cat. 73 Sewing kit in sealskin holder containing awls, hook and marking knife, Labrador Eskimo, Taylor cat. 70a Sealskin wall pouch (Inuit) Taylor cat. 74 Model snow shoes, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 3 Child’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 25 1 Taylor Collection List of Exhibits Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 62 Child’s single embroidered moccasin, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 234 Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 143ii Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais, Taylor cat. 143i Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Taylor cat.202b Beaded pouch from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. -

Cree-Naskapi (Of Quebec) Act Loi Sur Les Cris Et Les Naskapis Du Québec

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act Loi sur les Cris et les Naskapis du Québec S.C. 1984, c. 18 S.C. 1984, ch. 18 Current to November 9, 2016 À jour au 9 novembre 2016 Last amended on May 15, 2014 Dernière modification le 15 mai 2014 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (2) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (2) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. -

Gaelic Nova Scotia an Economic, Cultural, and Social Impact Study

Curatorial Report No. 97 GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy 1 Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada November 2002 Maps of Nova Scotia GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada Nova Scotia Museum 1747 Summer Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3A6 © Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Nova Scotia Museum, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Nova Scotia Museum at the above address. Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-88871-774-1 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section One: The Marginalization of Gaelic Celtic Roots 10 Gaelic Settlement of Nova Scotia 16 Gaelic Nova Scotia 21 The Status of Gaelic in the 19th Century 27 The Thin Edge of The Wedge: Education in 19th-Century Nova Scotia 39 Gaelic Language and Status: The 20th Century 63 The Multicultural Era: New Initiatives, Old Problems 91 The Current Status of Gaelic in Nova Scotia 112 Section Two: Gaelic Culture in Nova Scotia The Social Environment 115 Cultural Expression 128 Gaelic and the Modern Media 222 Gaelic Organizations 230 Section Three: Culture and Tourism The Community Approach 236 The Institutional Approach 237 Cultural Promotion 244 Section Four: The Gaelic Economy Events 261 Lessons 271 Products 272 Recording 273 Touring 273 Section Five: Looking Ahead Strengths of Gaelic Nova Scotia 275 Weaknesses 280 Opportunities 285 Threats 290 Priorities 295 Bibliography Selected Bibliography 318 INTRODUCTION Scope and Method Scottish Gaels are one of Nova Scotia’s largest ethnic groups, and Gaelic culture contributes tens of millions of dollars per year to the provincial economy.