Defining Rome: the Arch of Trajan at Beneventum Elizabeth Wolfram Thill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Republic to Principate: Change and Continuity in Roman Coinage

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ From republic to principate change and continuity in Roman coinage Gyori, Victoria Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Title: From republic to principate change and continuity in Roman coinage Author: Victoria Gyori The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

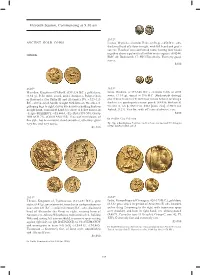

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

American Journal of Numismatics 26

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF NUMISMATICS 26 Second Series, continuing The American Numismatic Society Museum Notes THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY NEW YORK 2014 © 2014 The American Numismatic Society ISSN: 1053-8356 ISBN 978-0-89722-336-2 Printed in China Contents Editorial Committee v Jonathan Kagan. Notes on the Coinage of Mende 1 Evangeline Markou, Andreas Charalambous and Vasiliki Kassianidou. pXRF Analysis of Cypriot Gold Coins of the Classical Period 33 Panagiotis P. Iossif. The Last Seleucids in Phoenicia: Juggling Civic and Royal Identity 61 Elizabeth Wolfram Thill. The Emperor in Action: Group Scenes in Trajanic Coins and Monumental Reliefs 89 Florian Haymann The Hadrianic Silver Coinage of Aegeae (Cilicia) 143 Jack Nurpetlian. Damascene Tetradrachms of Caracalla 187 Dario Calomino. Bilingual Coins of Severus Alexander in the Eastern Provinces 199 Saúl Roll-Vélez. The Pre-reform CONCORDIA MILITVM Antoniniani of Maximianus: Their Problematic Attribution and Their Role in Diocletian’s Reform of the Coinage 223 Daniela Williams. Digging in the Archives: A Late Roman Coin Assemblage from the Synagogue at Ancient Ostia (Italy) 245 François de Callataÿ. How Poor are Current Bibliometrics in the Humanities? Numismatic Literature as a Case Study 275 Michael Fedorov. Early Mediaeval Chachian Coins with Trident-Shaped Tamghas, and Some Others 317 Antonino Crisà. An Eighteenth-Century Sicilian Coin Hoard from the Termini-Cerda Railway Construction Site (Palermo, 1869) 339 Review Articles 363 American Journal of Numismatics Andrew R. Meadows Oliver D. Hoover Editor Managing Editor Editorial Committee John W. Adams John H. Kroll Boston, Massachusetts Oxford, England Jere L. Bacharach Eric P. Newman University of Washington St. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603

Epigraphical Research and Historical Scholarship, 1530-1603 William Stenhouse University College London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Ph.D degree, December 2001 ProQuest Number: 10014364 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10014364 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis explores the transmission of information about classical inscriptions and their use in historical scholarship between 1530 and 1603. It aims to demonstrate that antiquarians' approach to one form of material non-narrative evidence for the ancient world reveals a developed sense of history, and that this approach can be seen as part of a more general interest in expanding the subject matter of history and the range of sources with which it was examined. It examines the milieu of the men who studied inscriptions, arguing that the training and intellectual networks of these men, as well as the need to secure patronage and the constraints of printing, were determining factors in the scholarship they undertook. It then considers the first collections of inscriptions that aimed at a comprehensive survey, and the systems of classification within these collections, to show that these allowed scholars to produce lists and series of features in the ancient world; the conventions used to record inscriptions and what scholars meant by an accurate transcription; and how these conclusions can influence our attitude to men who reconstructed or forged classical material in this period. -

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan Dynasty Owe Its Downfall to Its Ultimate Failure to Live up to Its Own Militaristic Identity?

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan dynasty owe its downfall to its ultimate failure to live up to its own militaristic identity? Exam Number: B043183 Master of Arts with Honours in Classical Studies Exam Number: B043183 1 Acknowledgements Warm thanks to Dr Matthew Hoskin for his keen supervision, and to Dr Alex Imrie for playing devil’s advocate and putting up with my daft questions. Thanks must also go to my family whose optimism and belief in my ability so often outweighs my own. Exam Number: B043183 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One – Living by the Sword 6 Chapter Two – Dying by the Sword 23 Chapter Three – Of Rocky Ground and Great Expectations 38 Conclusion 45 Bibliography 48 Word Count: 14,000 Exam Number: B043183 3 List of Illustrations Fig. 1. Chart detailing the percentage of military coin types promoted by emperors from Pertinax to Numerian inclusive (Source: Manders, E. (2012), Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, AD 193-284, Leiden, p. 65, fig. 17). Fig. 2. Portrait statue showing Caracalla in full military guise (Source: https://www.dailysabah.com/history/2016/08/02/worlds-only-single-piece-2nd-century- caracalla-statue-discovered-in-southern-turkey (Accessed 14/01/17). Fig. 3. Bust of Caracalla wearing sword strap and paludamentum (Source: Leander Touati, A.M. (1991), ‘Portrait and historical relief. Some remarks on the meaning of Caracalla’s sole ruler portrait’, in A.M. Leander Touati, E. Rystedt, and O. Wikander (eds.), Munusula Romana, Stockholm, 117-31, p. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is an author's version which may differ from the publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/94472 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. Identities of emperor and empire in the third century AD By Erika Manders and Olivier Hekster1 In AD 238, at what is now called Gressenich, near Aachen, an altar was dedicated with the following inscription: [to Iupiter Optimus Maximus]/ and the genius of the place for/ the safety of the empire Ma/ sius Ianuari and Ti/ tianus Ianuari have kept their promise freely to the god who deserved it, under the care /of Masius, mentioned above, and of Macer Acceptus, in [the consulship] of Pius and Proclus ([I(ovi) O(ptimo) M(aximo)] et genio loci pro salute imperi Masius Ianuari et Titianus Ianuari v(otum) s(olverunt) l(ibentes) m(erito) sub cura Masi s(upra) s(cripti) et Maceri Accepti, Pio et Proclo [cos.]).2 Far in the periphery of the Roman Empire, two men vowed to the supreme god of Rome and the local genius, not for the safety of the current rulers, but for that of the Empire as a whole. Few sources illustrate as clearly how, fairly early in the third century already, the Empire was thought, at least by some, to be under threat. At the same time though, the inscription makes clear how the Empire as a whole was perceived as a communal identity which had to be safeguarded by centre and periphery alike. -

The Acts of Augustus As Recouded on the Monumentum Ancyranum

THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS AS RECOUDED ON THE MONUMENTUM ANCYRANUM Below is a copy of the acts of the Deified Augustus by which he placed the whole world under the sovereignty of the Roman people, and of the amounts which he expended upon the state and the Roman people, as engraved upon two bronze colimins which have been set up in Rome.<» 1 . At the age of nineteen,* on my o>vn initiative and at my own expense, I raised an army " by means of which I restored Uberty <* to the republic, which the Mausoleum of Augustus at Rome. Its original form on that raonument was probably : Res gestae divi Augusti, quibus orbem terrarum imperio populi Romani subiecit, et impensae quas in rem publicam populumque Romanum fecit. " The Greek sup>erscription reads : Below is a translation of the acts and donations of the Deified Augustus as left by him inscribed on two bronze columns at Rome." * Octa\ian was nineteen on September -23, 44 b.c. « During October, by offering a bounty of 500 denarii, he induced Caesar's veterans at Casilinum and Calatia to enlist, and in Xovember the legions named Martia and Quarta repudiated Antony and went over to him. This activity of Octavian, on his own initiative, was ratified by the Senate on December 20, on the motion of Cicero. ' In the battle of Mutina, April 43. Augustus may also have had Philippi in mind. S45 Source: Frederick W. Shipley, Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History. Res Gestae Divi Augusti, LCL (Cambridge, MA: HUP, 19241969). THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS, I. -

Roman Soldier Germanic Warrior Lindsay Ppowellowell

1st Century AD Roman Soldier VERSUS Germanic Warrior Lindsay Powell © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 1st Century ad Roman Soldier Germanic Warrior Lindsay PowellPowell © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION 4 THE OPPOSING SIDES 10 Recruitment and motivation t Morale and logistics t Training, doctrine and tactics Leadership and communications t Use of allies and auxiliaries TEUTOBURG PASS 28 Summer AD 9 IDISTAVISO 41 Summer AD 16 THE ANGRIVARIAN WALL 57 Summer AD 16 ANALYSIS 71 Leadership t Mission objectives and strategies t Planning and preparation Tactics, combat doctrine and weapons AFTERMATH 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Introduction ‘Who would leave Asia, or Africa, or Italia for Germania, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?’ (Tacitus, Germania 2). This negative perception of Germania – the modern Netherlands and Germany – lay behind the reluctance of Rome’s great military commanders to tame its immense wilderness. Caius Iulius Caesar famously threw a wooden pontoon bridge across the River Rhine (Rhenus) in just ten days, not once but twice, in 55 and 53 bc. The next Roman general to do so was Marcus Agrippa, in 39/38 bc or 19/18 bc. However, none of these missions was for conquest, but in response to pleas for assistance from an ally of the Romans, the Germanic nation of the Ubii. It was not until the reign of Caesar Augustus that a serious attempt was made to annex the land beyond the wide river and transform it into a province fit for Romans to live in. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

How to Invoke the Gods in the Roman World: Examples from the Arval Brethren

How to Invoke the Gods in the Roman World: Examples from the Arval Brethren The purpose of this paper is to identify and examine the different techniques Roman priests used to invoke the gods in order to draw conclusions about the knowledge base of priests, the functions of ritual and religion, and Roman conceptions of the gods. Specifically, the Arval Brethren, and by extension Roman priests, would tailor their invocations to the given ritual circumstances. They would do so by either focusing their invocation on only a particular aspect of a deity’s power or they would deliberately invoke a deity in its entirety. This permitted the Roman priests a high degree of flexibility in calling down the god, or aspect of a god, best suited to the ritual circumstances. The functional mechanics behind priestly invocation has not been meaningfully studied for a century since Georg Wissowa (Wissowa, 1912). Recent theoretical developments in the fields of sociology, anthropology, and religious studies suggest that a reevaluation of the core principles of Roman religion would yield new insights into the role and importance of Roman religion in the ancient world. Other modern studies reassessing the theological and practical underpinnings of Roman religion, such as the relationship between the gods and Roman society, and the practice of Roman religion (Ando, 2008; Scheid, 1999), have yielded beneficial results. Though this paper includes examples from multiple priestly colleges, including the Pontifices (CIL 11.4172), Augures (CIL 14.2580), and Salii (Carmen Saliare), the Acta of the Arval Brethren remains by far the largest surviving source of recorded ritual among the Romans.