Roman Coins Elementary Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

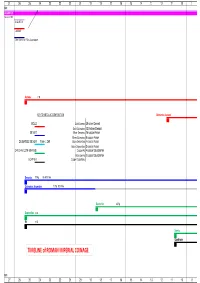

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

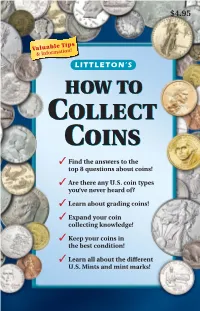

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

Wars and Battles of Ancient Rome

Wars and Battles of Ancient Rome Battle summaries are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904. Rise of Rome—753 to 3911 B.C. The rise of Rome from a small Latin city to the dominant power in Italy Battle of Description Sabines According to legend, a year after the Romans kidnapped their wives from the neighboring Sabines, the (Kingdom) tribes returned to take vengeance. The fighting however, was stopped by the young wives who ran in B.C. 750 between the warring parties and begged that their fathers, brothers and husbands cease making war upon each other. The Sabine and Roman tribes were henceforth united. Alba Longa After a long siege, Alba was finally taken by strategm. With the fall of Alba, its father-city, Rome was (Kingdom) the undisputed leading city of the Latins. The inhabitants of Alba were resettled in Rome on the caelian B.C. 650 Hill. Sublican Lars Porsenna, king of Clusium was marching toward Rome, planning to restore the exiled Tarquins to Bridge the Roman throne. As his army descended on Rome from the opposite side of the Tiber, roman soldiers (Tarquinii) worked furiously to destroy the wooden bridge. Horatius and two other soldiers single-handedly fended B.C. 509 off Porsenna's army until the bridge could be destroyed. Lake Regillus Fought B.C. 497, the first authentic date in the history of Rome. The details handed down, however, (Tarquinii) belong to the domain of legend rather than to that of history. According to the chroniclers, this was the B.C. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Lincoln Harris Blumell Department of Ancient Scripture Brigham Young University 210F JSB, Provo, UT 84602 [email protected] www.lincolnhblumell.com W (801) 422-2497 C (801) 822-9633 Employment Brigham Young University, Department of Ancient Scripture, Associate Professor (Ancient Christianity) Sept. 2016 – present Brigham Young University, Department of Ancient Scripture, Assistant Professor (Ancient Christianity) July 2010 – Aug. 2016 Tulane University, Department of Classical Studies, Visiting Assistant Professor (Ancient Christianity) July 2009 – June 2010 Education Ph.D. University of Toronto, 2009 (Religious Studies, Ancient Christianity) Dissertation Lettered Christians: Christians, Letters, and Late Antique Oxyrhynchus Supervisor: John Kloppenborg External Examiner: Eldon Epp M.St. Christ Church, University of Oxford, 2004 (Jewish Studies) Thesis Galilean Social Bandits? An Examination of Galilean Brigandage from Herod the Great to the Outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt Against Rome (First Class Hons.) Supervisor: Sir Fergus Millar M.A. University of Calgary, 2003 (Religious Studies, Specialization in Western Religions) Thesis The Early Roman Emperors and the Christians: An Examination of the Early Emperors’ Ascribed Position as “Persecutors” of the Christians Supervisor: Wayne McCready B.A. (Hons.) University of Calgary, 2001 (Classical Studies) Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Spring Semester 2000 1 Monographs Didymus the Blind’s Commentary on Psalms 26:10–29:2 and 36:1–3. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2019. xv + 210 pp. (lead editor; with T. W. Mackay and G. Schwendner). Christian Oxyrhynchus: Texts, Documents, and Sources (Second through Fourth Centuries). Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2015. xxi + 778 pp. (with T. A. Wayment) Winner of the 2016 Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award from the Department of Ancient Scripture, Brigham Young University Lettered Christians: Christians, Letters, and Late Antique Oxyrhynchus. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

South Carolina Vs Clemson (11/22/1986)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1986 South Carolina vs Clemson (11/22/1986) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "South Carolina vs Clemson (11/22/1986)" (1986). Football Programs. 185. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/185 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. — None Can Compete When You Compare Batsoi is the exclusive U.S. agent for textile equipment from the leading textile manufacturers worldwide. Experienced people back up our sales with complete service, spare parts, technical assistance, training and follow-up. DREF 3 Friction Spinning Machine Excellent for Core Yarns and Multi-Component Yarns. Count range 3.5c.c. to 18c. c. Delivery speeds to 330 yds/min. Van de Wiele Plush Weaving Machines—Weave apparel, upholstery, and carpets. Compact, high-speed machines guarantee high productivity. Dornier Rapier Weaving Machine—Versatile enough to weave any fabric. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM Vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS PARS COMMUNIS SECUNDA AB VERBO CABOCHON AD VERBUM EXZESS cum indicibus MI))CCCXCVIII verborum Germanico-Latinorum AUCTORE PETRO LUCUSALTIANO LATINOPHILO MARES. IN OFF. CEN. editio XXI electronica die XVII mensis Ianuarii anno MMXXI r.n.t. Dicasterium ad Relatinizandum Orbem Terrarum in Officio Centrale Via Raimundi XXXIX, Lentia ad Danuvium Regio Austria Superior Privilegium impressorium Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili, Codice Iuris Supremi 1 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index generalis Inhaltsverzeichnis Pagina Caput 1 Titulus huius libri 2 Index generalis 3 Notae 4 Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum litterarum C - E 4 Littera C 22 Littera D 68 Littera E 2 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Notae Abkürzungen Abbr: abbrevatio abl casus ablativus abl abs ablativus absolutus adv adverbum a.r.n.t. ante rationem nostri temporis ca. circa f femininum gen casus genitivus lib. liber m masculinum n neutrum num verbum numerale pl verbum plurale r.n.t. ratione nostri temporis * vocabulum novum huius editionis () optio adiuncta [] fontes librorum {} explanationes verborum ► verbum simile vel propinquum verbum vocabulum excellens verbum vocabulum malum [med.] vocabulum latinitatis mediaevalis [p.] pagina [vet.] vocabulum latinitatis veteris [XXX] Litteris maiusculis in fibulis angulatis notantur libri adhibiti. [YYY] vocabulum in statu „Alpha“ 3 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum Verzeichnis der Deutsch-Lateinischen Vokabeln C ( 4 0 3 ) CA Cabochon ► Cabochonschliff Cabochonschliff, m politura tumulosa, f [2014] {gemmae} Cabrio ► Cabriolet Cabriolet, n cisium, i, n [vet.; LEA p.295; GHL I,1177] {autocinetum cum tegmine apertili [NLL p.75,1; VBC]} Cachaça, f ca(s)chassa, ae, f [LML 09.07.2009] {aqua ardens sacchari Brasiliensis} Cachaça..