Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

Bullionism, Specie-Point Mechanism and Bullion Flows in the Early 18Th-Century Europe

Bullionism, Specie-Point Mechanism and Bullion Flows in the Early 18th-century Europe Pilar Nogués Marco ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

Francis Hopkinson, a Pretty Story Written in the Year of Our Lord 2774

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION An allegory of the causes of the American Revolution Maryland Historical Society A PRETTY STORY WRITTEN IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 2774 by PETER GRIEVOUS, ESQUIRE [Francis Hopkinson] Williamsburg, Virginia, 1774 ___ EXCERPTS * A lawyer, statesman, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a widely read political satirist, Francis Hopkinson penned this acerbic yet witty fable Francis Hopkinson depicting the road to revolution in the American colonies. self-portrait after 1785 portrait by Robert Edge Pine C H A P T E R I . * nce upon a time, a great while ago, there lived a certain Nobleman who had long possessed a very valuable farm and had a great number of children and grandchildren. Besides the annual O profits of his land, which were very considerable, he kept a large shop of goods; and, being very successful in trade, he became, in process of time, exceeding rich and powerful, insomuch that all his neighbors feared and respected him. With respect to the management of his family, it was thought he had adopted the most perfect mode that could be devised, for he had been at the pains to examine the economy of all his neighbors and had selected from their plans all such parts as appeared to be equitable and beneficial, and omitted those which from experience were found to be inconvenient; or rather, by blending their several constitutions together, he had so ingeniously counterbalanced the evils of one mode of government with the benefits of another that the advantages were richly enjoyed and the inconveniencies scarcely felt. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY John Swanwick: Spokesman for "Merchant-Republicanism ' In Philadelphia, 1790-179 8 HE literature on the era of Jeffersonian democracy is largely- dominated by the great triumvirate of Thomas Jefferson, TJames Madison, and Albert Gallatin.* During the last dec- ade, however, historians have been paying more attention to state and local political leaders who played significant roles in the Demo- cratic-Republican movement.1 Among the more notable second-rank * In a somewhat abbreviated form this article was presented as a paper at the annual meeting of the Pennsylvania Historical Association held at Williamsport, Pa., on Oct. 22-23, 1971. The author wishes to express his gratitude to his colleague, Bernard Sternsher, for his helpful editorial suggestions. 1 Historians have given most of their attention to secondary Federalists, but since i960 the number of modern scholarly biographies of less prominent Republicans has increased. We now have first-rate biographies on Robert R. Livingston, David Rittenhouse, Aaron Burr, Daniel D. Tompkins, John Breckinridge, Luther Martin, Benjamin Rush (2), Samuel Smith, and James Monroe. There are also a number of good unpublished doctoral dissertations. Among the more notable studies are those on Elkanah Watson, Simon Snyder, Mathew Carey, Samuel Latham Mitchell, Melancton Smith, Levi Woodbury, William Lowndes, William Duane, William Jones (2), Eleazer Oswald, Thomas McKean, Levi Lincoln, Ephraim Kirby, and John Nicholson. Major biographies of Tench Coxe by Jacob E. Cooke, of John Beckley by Edmund Berkeley, and of Thomas McKean by John M. Coleman and Gail Stuart Rowe are now in progress. 131 132 ROLAND M. -

British Commemorative Medals

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Gold Medals 2074 Victoria, Golden Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by L C Wyon, after Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and (reverse), Sir Frederick Leighton, crowned and veiled bust left, rev the Queen enthroned with figures of the arts and industry around her, 58mm, 89.86g, in red leather case of issue (BHM 3219). Extremely fine, damage to clasp of case. £900-1100 944 specimens struck, selling at 13 Guineas each 2075 Victoria, Diamond Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by G W -

Landmark Towns Regional Revitalization Strategy

LANDMARK TOWNS REGIONAL REVITALIZATION STRATEGY Introduction The Landmark Towns Initiative is a cooperative venture between the historic boroughs of Bristol, Morrisville, New Hope and Yardley Pennsylvania The purpose of the Landmark Towns Initiative is to establish a regional approach to economic development and community revitalization focused on the commercial opportunities and growth in tourism identified by four the Delaware riverfront boroughs of Bristol, Morrisville, New Hope and Yardley Bucks County. To pursue these opportunities, the four municipalities joined with the Delaware & Lehigh Heritage Corridor Commission Inc., in a 'Cooperative Venture' in the spring of 2006 and produced a scope of work and a work plan. This $25,000 planning effort, (see attached) was self funded and has resulted in the development of this following strategic plan. Since September of 2006, staff of the Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor Commission and the selected consulting firm of Keystone Heritage Group LLC. have worked with the four municipalities to develop this strategic plan. This effort, which has been done in regular consultation with Ms. Antoinette Crawford Major, Regional Director DCED, has included town meeting and site visits within each municipality, meetings with various stakeholders and regular monthly meetings of the Landmark Towns of Bucks County Steering Committee They are now seeking the Commonwealth's support, through the New Communities Program, for participation in the multi-year Regional Coordinators Program Elements -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

Coins and Medals;

CATALOGUE OF A VERY IKTERESTIKG COLLECTION'' OF U N I T E D S T A T E S A N D F O R E I G N C O I N S A N D M E D A L S ; L ALSO, A SMx^LL COLLECTION OF ^JMCIEjMT-^(^REEK AND l^OMAN foiJMg; T H E C A B I N E T O F LYMAN WILDER, ESQ., OF HOOSICK FALLS, N. Y., T O B E S O L D A T A U C T I O N B Y MJSSSBS. BAjYGS . CO., AT THEIR NEW SALESROOMS, A/'os. yjg and ^4.1 Broadway, New York, ON Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, May 21, 23 and 2Ji,, 1879, AT HALF PAST TWO O'CLOCK. C a t a l o g u e b y J o l a n W . H a s e l t i n e . PHILADELPHIA: Bavis & Phnnypackeh, Steam Powee Printers, No. 33 S. Tenth St. 1879. j I I I ih 11 lii 111 ill ill 111 111 111 111 11 1 i 1 1 M 1 1 1 t1 1 1 1 1 1 - Ar - i 1 - 1 2 - I J 2 0 - ' a 4 - - a a 3 2 3 B ' 4 - J - 4 - + . i a ! ! ? . s c c n 1 ) 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 'r r '1' '1' ,|l l|l 1 l-Tp- S t ' A L E O P O n e - S i x t e e n t h o f a n I n c h . -

HI 2108 Reading List

For students of HI 2106 – Themes in modern American history and HI 2018 – American History: A survey READING LISTS General Reading: 1607-1991 Single or two-volume overviews of American history are big business in the American academic world. They are generally reliable, careful and bland. An exception is Bernard Bailyn et al, The Great Republic: a history of the American people which brings together thoughtful and provocative essays from some of America’s top historians, for example David Herbert Donald and Gordon Wood. This two-volume set is recommended for purchase (and it will shortly be available in the library). Other useful works are George Tindall, America: a Narrative History, Eric Foner, Give me Liberty and P.S. Boyer et al, The Enduring Vision all of which are comprehensive, accessible up to date and contain very valuable bibliographies. Among the more acceptable shorter alternatives are M.A. Jones, The Limits of Liberty and Carl Degler, Out of our Past. Hugh Brogan, The Penguin history of the United States is entertaining and mildly idiosyncratic. A recent highly provocative single- volume interpretative essay on American history which places war at the centre of the nation’s development is Fred Anderson and Andrew Cayton, The Dominion of War: Empire and Liberty in North America, 1500-2000 All of the above are available in paperback and one should be purchased. Anthologies of major articles or extracts from important books are also a big commercial enterprise in U.S. publishing. By far the most useful and up-to-date is the series Major problems in American History published by D.C. -

Inside the U.S. Mint

#9246 IINNSSIIDDEE TTHHEE UU..SS.. MMIINNTT AMBROSE VIDEO PUBLISHING 2000 Grade Levels: 9-13+ 50 minutes 1 Instructional Graphic Enclosed DESCRIPTION Describes the process of minting U.S. coins: creating and selecting their designs, finding correct metals, creating new dies, striking and inspecting new coins. Features the gold-refining process for the Canadian gold Maple Leaf and the enormously complex problems faced when replacing the national currencies of Europe with the new Euro-dollar. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: Civics • Standard: Understands how the United States Constitution grants and distributes power and responsibilities to national and state government and how it seeks to prevent the abuse of power Benchmark: Knows which powers are primarily exercised by the state governments (e.g., education, law enforcement, roads), which powers are prohibited to state governments (e.g., coining money, conducting foreign relations, interfering with interstate commerce), and which powers are shared by state and national governments (e.g., power to tax, borrow money, regulate voting) Subject Area: Economics • Standard: Understands basic features of market structures and exchanges Benchmark: Knows that the basic money supply is usually measured as the total value of coins, currency, and checking account deposits held by the public INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To observe coin-making inside the U.S. Mint. 2. To present the Royal Canadian Mint. 3. To illustrate the process of European countries switching to the Euro dollar. 4. To provide statistics on minted coins. 1 Captioned Media Program VOICE 800-237-6213 • TTY 800-237-6819 • FAX 800-538-5636 • EMAIL [email protected] • WEB www.cfv.org Funding for the Captioned Media Program is provided by the U.S. -

Strobridge-18711205.Pdf

CATALOGUE OF A V A L U A B L E C O L L E C T I O N OF ivr. td.^ OF MANCHESTER, ENGLAND. ' X ' v O ) f t ' f , BY G t E O . & C o . , a t t h e i r s a l e s r o o m s , Clinton 3^aU, J^stor Jflace, ON T U E S D AY, W E D N E S D AY, & T H U R S D AY E V E N I N G S , Dopcmbcr r,tli, 6Ui ami Vtli, 1S71, RALE TO COMMENCE EACH DAY AT J o'cLOCK. CATALOGUE BY W. II. STROBRIDGE, 425 I1AMII.T0N Street, Brooklyn. XlSr Collectors arc roqiiosted to bcikI tlicir orilers throiigli tlic iienal chnnncls, nnd tliey •will 1)0 faltlifully cxcciitod by tlie Auctioneers. INTEODUCTION. I t i s n o w s o m e t e n o r t w e l v e y e a r s s i n c e t h e n a m e o f Dr. Charles Clay, of Manchester, England, became known to American collectors, in connection with an alreaclj"^ celebrated Cabinet of Coins. American travellers, with antiquarian tastes, have been in the habit of calling upon this genial and enthusiastic collector, at his home, and viewing his rarities, many of which were to be seen nowhere else. From these gentlemen, the fame of Dr. Clay's collection has spread far and wide; besides, the Dr. has never been slow to furnish his correspondents on this side of the Atlantic with rubbings and descriptions of his most valued pieces. -

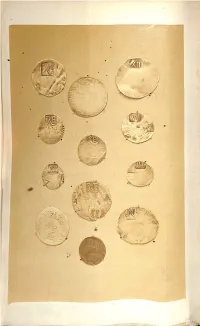

O·HE Monetary Systems of the British Possessions in the West

THE SPANISH DOLLAR AS ADAPTED FOR CURRENCY IN OUR 'VEST INDIAN COLONIES. By J. B. CALDECOTT. · HE monetary systems of the British Possessions in the West Indies form a most interesting chapter in the history of O currency; a chapter that embraces many mediums of exchange, that is fertile in experiments, that comprises many strange expedients and perhaps more than its due share of errors and of failur es. N umismatologists are often accused of a certain want of breadth in their studies ; but the history of the currency of our West Indian colonies is full of interest both from financial and numismatic stand points, and the future historian must be able to deal with it from both these points of view. Our older colonies in this quarter of the globe have passed through the various stages of barter, of metallic mediums, and of paper currencies, and in the second of these stages have used gold, silver and copper both at their intrinsic and at token valu es ; also, whilst allowing circulation to the coinages of many nations, they have been singularly destitute of any special issues of their own. Chief amongst these foreign coins have been those of Spain, and it is with the use of the Spanish dollar in our W est Indian Possessions that this short and, in the present state of our knowledge, necessaril y incomplete account deals. Situated as these islands were, surrounded by the American possessions of Spain-the resort alik e of those who carried on com merce with th ese possessions, and of buccaneers who, as occas ion 288 Th e Spanislz Dollar as Adapted for offered, preyed upon them and th eir ships; it was natural th at the Spanish dollar and its fracti ons sh ould form a large portion of their silver circulating medium.