Histoire & Mesure, XVII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

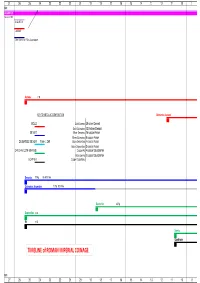

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-45597-8 — Cultural Encounters on Byzantium's Northern Frontier, C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-45597-8 — Cultural Encounters on Byzantium's Northern Frontier, c. AD 500–700 Andrei Gandila Index More Information Index 12-nummia, 225–226, 233, 235 Anemurium, 55, 58 Abasgi, 192, 198, 200, 204–205, 217 Ani, 199, 204, 206, 209 Abasgia, 201, 203–204 Annaeus Florus, 22 Abkhazia, 96, 199, 201, 204, 210 annona, 46, 48, 69, 139, 142, 150, 162, 283 Accres, 86 Antes, 4, 86, 92, 128, 141, 144, 156, 173, 190, acculturation, 136, 287 265, 268, 270, 280, 287 Adamclisi, 55–56, 73, 79, 93, 182 Antioch, 159, 172, 177, 180–181, 185, Adjovski gradec, 48 200–201, 207 Adriatic Sea, 53, 63, 148, 157, 222 Apalina, 225 Aegean Sea, 53, 63–64, 162, 182 Apsili, 192, 198, 200, 205 Agathias, 18, 22, 176, 194, 201, 286 Apsilia, 201, 204–205 Aila, 191 Apulum. See Alba-Iulia Ak’ura, 213 Aquis, 56, 59, 80, 96, 115, 184 Akhali Atoni, 201 Arabia, 132, 152, 203, 232 Akhaltsikhe, 207 Arabs, 1, 187, 214–215 Akhtopol, 189 Arad, 236 Alamans, 26 Araxes river, 208, 215 Alans, 192, 202–203, 207 Archaeopolis, 157, 198, 200, 207, 209, Alba-Iulia, 55–56, 61, 64, 107 212–213 Albania, 18, 90, 194, 196, 206–208, 211 Archar, 53 Alboin, king, 230 Ardagast, 170, 182 Alcedar-Odaia, 274 Argamum, 74 Alexandretta, 235 Argeș river, 170 Alexandria, 189, 201, 225–226, 233, 235 aristocracy. See elites Alföldi, Andreas, 11, 20 Aristotle, 258 Almăjel, 171 Armenia, 7, 194, 198–200, 202, 204, 206, Alps, 122, 217, 232, 287 209–211, 213–215, 217 Amasra, 201 Prima, 196 Amasya, 196 Secunda, 196 Ambéli, 254, 256 Arnoldstein, 231 Ambroz, A. -

Aux Débuts De L'archéologie Moderne Roumaine: Les Fouilles D'atmageaua

Aux débuts de l’archéologie moderne roumaine: les fouilles d’Atmageaua Tătărască∗ Radu-Alexandru DRAGOMAN** Abstract: This text is an analysis of the archive resulting from the 1929-1931, 1933 and 1935 archaeological research at Atmageaua Tătărască, southern Dobrudja (today Sokol, in Bulgaria). The excavations at Atmageaua Tătărască are relevant for the history of Romanian archeology because they correspond to the time of formation and institutionalization of a scientific approach considered to be “modern” and of a research philosophy that would dominate the archaeological practice ever since. The text seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the beginnings of the discipline and also advocates for the redefinition of the current archaeological practice. Rezumat: Textul reprezintă o analiză a arhivei rezultate în urma cercetărilor arheologice din 1929-1931, 1933 şi 1935 de la Atmageaua Tătărască, sudul Dobrogei (astăzi Sokol, în Bulgaria). Săpăturile de la Atmageaua Tătărască sunt relevante pentru istoria arheologiei românești, deoarece corespund perioadei de formare şi instituţionalizare a unei demers ştiinţific considerat a fi „modern” şi a unei filosofii de cercetare ce va domina practica arheologică de atunci încolo. Textul își propune să contribuie la o mai bună înțelegere a începuturilor disciplinei și, totodată, pledează pentru redefinirea practicii arheologice din prezent. Keywords: History of archaeology, modern archaeology, “lovers of antiquities”, archive, Atmageaua Tătărască, Romania. Cuvinte-cheie: Istoria arheologiei, arheologie modernă, „pasionaţii de antichităţi”, arhivă, Atmageaua Tătărască, România. ≤ Introduction Pendant la première guerre mondiale, lorsque l’armée roumaine, qui luttait près d’Entente, avait été vaincue et une partie du pays occupée par les troupes des Empires Centraux, les archéologues Allemands ont entrepris des fouilles dans plusieurs sites préhistoriques de la Roumanie (Vl. -

Manual on Border Controls Along the Danube and Its Navigable Tributaries

EU Strategy for the Danube Region Priority Area 1a – To improve mobility and multimodality: Inland waterways Practical manual on border controls along the Danube and its navigable tributaries Author(s): Milica Gvozdic (viadonau) Simon Hartl (viadonau) Katja Rosner (viadonau) Version (date): 31.08.2015 1 General information .................................................................................................................. 4 2 How to use this manual? .......................................................................................................... 5 3 Geographic scope .................................................................................................................... 5 4 Hungary ................................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 General information on border controls ................................................................................... 7 4.1.1 Control process ................................................................................................................... 8 4.1.2 Control forms ..................................................................................................................... 10 4.1.3 Additional information ....................................................................................................... 21 4.2 Information on specific border control points ......................................................................... 22 4.2.1 Mohács ............................................................................................................................. -

The Evolution of Civil and Military Habitat in the Period Latène on the Territory of Romania

Iulian BOLDEA, Cornel Sigmirean (Editors), DEBATING GLOBALIZATION. Identity, Nation and Dialogue Section: History, Political Sciences, International Relations THE EVOLUTION OF CIVIL AND MILITARY HABITAT IN THE PERIOD LATÈNE ON THE TERRITORY OF ROMANIA Ioana Olaru PhD, “George Enescu” National University of Arts, Iaşi Abstract:In this paper, we will focus on the second period of the Iron Age, Latène (in fact, only its first two phases, the one of formation and spreading, after which the inhabitants of these territories will enter Antiquity, for Prehistory has ended), presented from the point of view of its settlements, and also of the civil and military constructions. The settlements and tenements of the entire Iron Age reflect the continuity of migrations, through limited, through the sedentarization and fortification of many of the settlements, which became true centres of unions of tribes. The urbanization process started in Hallstatt will continue in Latène, in the context of development of tribal aristocracy, as a result of unions of tribes that became more and more stable. Becoming bigger and bigger, the population needed bigger settlements, fortified, whose evolution will be monitored, from the davae of the Dacians from the forming period, to the quasi-urban settlements from the second period, the one of spreading during the period Latène, in the great fortresses built now (that will continue their development during the time of Burebista). The buildings become more and more complex, there are three types of described plans: rectangular, apse like, circular, and also the tower-tenements. Keywords: murus dacicus, opus quadratum, opus mixtum, megaron, emplecton Alcătuită din Epoca bronzului și Epoca fierului, Epoca metalelor este perioada în care apar primele semne ale unei revoluții statal-urbane, iar uneltele din piatră sunt înlocuite cu cele din metal (proces început încă de la sfârșitul Eneoliticului). -

Treaty Concerning the Accession of the Republic of Bulgaria and Romania to the European Union CM 6657

European Communities No. 2 (2005) Treaty between the Kingdom of Belgium, the Czech Republic, the Kingdom of Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany, the Republic of Estonia, the Hellenic Republic, the Kingdom of Spain, the French Republic, Ireland, the Italian Republic, the Republic of Cyprus, the Republic of Latvia, the Republic of Lithuania, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Malta, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Republic of Austria, the Republic of Poland, the Portuguese Republic, the Republic of Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, the Republic of Finland, the Kingdom of Sweden, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (Member States of the European Union) and the Republic of Bulgaria and Romania concerning the accession of the Republic of Bulgaria and Romania to the European Union Luxembourg, 25 April 2005 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty August 2005 Cm 6657 £39·60 European Communities No. 2 (2005) Treaty between the Kingdom of Belgium, the Czech Republic, the Kingdom of Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany, the Republic of Estonia, the Hellenic Republic, the Kingdom of Spain, the French Republic, Ireland, the Italian Republic, the Republic of Cyprus, the Republic of Latvia, the Republic of Lithuania, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Malta, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Republic of Austria, the Republic of Poland, the Portuguese Republic, the Republic -

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM Vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS PARS COMMUNIS SECUNDA AB VERBO CABOCHON AD VERBUM EXZESS cum indicibus MI))CCCXCVIII verborum Germanico-Latinorum AUCTORE PETRO LUCUSALTIANO LATINOPHILO MARES. IN OFF. CEN. editio XXI electronica die XVII mensis Ianuarii anno MMXXI r.n.t. Dicasterium ad Relatinizandum Orbem Terrarum in Officio Centrale Via Raimundi XXXIX, Lentia ad Danuvium Regio Austria Superior Privilegium impressorium Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili, Codice Iuris Supremi 1 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index generalis Inhaltsverzeichnis Pagina Caput 1 Titulus huius libri 2 Index generalis 3 Notae 4 Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum litterarum C - E 4 Littera C 22 Littera D 68 Littera E 2 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Notae Abkürzungen Abbr: abbrevatio abl casus ablativus abl abs ablativus absolutus adv adverbum a.r.n.t. ante rationem nostri temporis ca. circa f femininum gen casus genitivus lib. liber m masculinum n neutrum num verbum numerale pl verbum plurale r.n.t. ratione nostri temporis * vocabulum novum huius editionis () optio adiuncta [] fontes librorum {} explanationes verborum ► verbum simile vel propinquum verbum vocabulum excellens verbum vocabulum malum [med.] vocabulum latinitatis mediaevalis [p.] pagina [vet.] vocabulum latinitatis veteris [XXX] Litteris maiusculis in fibulis angulatis notantur libri adhibiti. [YYY] vocabulum in statu „Alpha“ 3 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum Verzeichnis der Deutsch-Lateinischen Vokabeln C ( 4 0 3 ) CA Cabochon ► Cabochonschliff Cabochonschliff, m politura tumulosa, f [2014] {gemmae} Cabrio ► Cabriolet Cabriolet, n cisium, i, n [vet.; LEA p.295; GHL I,1177] {autocinetum cum tegmine apertili [NLL p.75,1; VBC]} Cachaça, f ca(s)chassa, ae, f [LML 09.07.2009] {aqua ardens sacchari Brasiliensis} Cachaça.. -

ROBG-174 Your Health Matters! - Modernization of the Hospitals in Zimnicea and Svishtov

Interreg V-A Romania-Bulgaria Programme Priority Axis 5 – An efficient region ROBG-174 Your Health Matters! - Modernization of the hospitals in Zimnicea and Svishtov What’s the goal? To improve the efficiency of health services and the collaboration between health care providers at the level of communities from Zimnicea and Svishtov. What’s the budget? 1,475,894.96 euro, out of which 1,254,510.72 ERDF Target at the half of the implementation period: 9,824 euro for Lead Beneficiary and 8,923 euro for Beneficiary 2. Who is doing it? Lead partner: Territorial Administrative Unit Zimnicea Town (Romania) Partner: Svishtov Municipality (Bulgaria) When is it happening? Start date: 13.04.2017 End date: 12.04.2019 Duration: 24 months Where is it happening? Zimnicea Town, Teleorman County, Romania Svishtov Town, Veliko Tarnovo District, Bulgaria Interreg V-A Romania-Bulgaria Programme Priority Axis 5 – An efficient region How is it going to happen? Organizing press 2 conferences (60 participants/conference) during the project implementation period (project launching conference – year 1 in Romania, 1 final conference during year 2 in Romania); Organizing 2 local conferences in Bulgaria (30 participants/conference) during the project implementation period (project launching conference, 1 final conference during year 2); Publicity materials (roll-up, flyer, outdoor banners, folders) Modernization of the hospital in Zimnicea; Modernization of the hospital in Svishtov; Exchange of experience and best practices. What will be the results (what’s the contribution to the Programme)? Programme outputs: - 1 supported cross border mechanism to enhance cooperation capacity – development of the existing cooperation between the 2 beneficiaries through: strengthening theirs capacity to provide health care services and the exchange of experience between health care employees; Programme results: increased level of co-ordination of the public institutions in the eligible area – the cooperation between the 2 beneficiaries will be strengthen through the project activities. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Let's Look at Evidence for Auxiliary

Auxiliary swords worn on the left. What of the auxiliary troops? Let’s look at evidence for auxiliary soldiers wearing their swords on the There has been a lot of discussion between the left. Continuing with the reliefs of the Adamklissi members of the auxilia recently, regarding the monument, there are metopes of auxiliary soldiers, wearing of swords on the left. Traditionally thought many of cavalrymen and another of three auxiliary to have been a reserve of the Centurionate. We have infantrymen showing baldrics slung over the right been looking at evidence that some auxiliaries may shoulder. have also worn their swords on the left. The first example is Metope 14. It clearly shows The Centurionate three soldiers with mail shirts carrying oval clipeus- Numerous tombstone reliefs show centurions with type shields (Legionaries on the monument are all their swords on the left. The Adamklissi monument, depicted with curved rectangular scuta) wearing or Tropaeum Traiani (dating from the reign of the their scabbards on the left side. The three Roman emperor Trajan) also depicts two centuriones (One soldiers advance towards the right with swords with his vine stick) in undress order wearing their drawn. A midrib is depicted on the swords. They scabbards on the left. Another, second metope shows wear helmets with deep neck guards and thigh- what at first glance also appear to be centuriones but length, short-sleeved, mail shirts over short tunicae this time both carrying what look to be scrolls. (typical of all the auxiliary soldiers depicted on Again the sword hangs on the left side. -

Trabalhos De Arqueologia 13

1. Sistema Monetário Tradicionalmente, na óptica numismática, o século IV d.C. inicia-se na época de Dio- cletianus porque é neste momento que têm lugar modificações importantes que restabe- lecem um sistema monetário, degradado no decurso do século III. Várias reformas mone- tárias marcam o decorrer do século, no qual, progressivamente, o papel da moeda de ouro e prata se vai afirmando, ao mesmo tempo que o da moedagem de bronze, sujeita a nume- rosas atribulações, diminui. A morte de Theodosius, no ano 395, e a divisão do Império entre os seus filhos Arcadius e Honorius terão repercussão na política monetária. Do ponto de vista numismático, o final do século IV d.C. é dominado por pequenas espécies de talhe Ae4. Um dos problemas que a moeda de bronze do século IV d.C. suscita e que ainda está por resolver é o da denominação atribuída na época às diferentes moedas que hoje conhe- cemos. Não existem fontes contemporâneas que testemunhem claramente tais nomes, e, quando estes aparecem naquelas, é muito difícil discernir com exactidão a que moeda fazem referência. A tradição instituiu o muito discutido termo follis para designar o “grande bronze” criado por Diocletianus em 294 e, consequentemente, também todos os sucessores daquela moeda. Hoje em dia, este termo está praticamente abandonado pelos investigado- res em favor de nummus; na altura, o follis designaria uma moeda de conta. Os únicos nomes conhecidos são o de maiorina e o de centenionalis, que surgem mencionados na lei do Codex Theodosianus, IX., 23. 1 de 354. Outra lei de 395, C. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements.