A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/107013 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-10 and may be subject to change. ANDREAS JOZEF JANSSEN HET ANTIEKE TROPAION 1957 N.V. DRUKKERIJ ERASMUS — LEDEBERG/GENT / HET ANTIEKE TROPAION PROMOTOR .· Prof. Dr. F. J. DE WAELE HET ANTIEKE TROPAION (with a Summary in English) AKADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE LETTEREN EN WIJSBEGEERTE AAN DE R. K. UNIVERSITEIT TE NIJMEGEN, OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAG NIFICUS DR. W. K. M. GROSSOü W, HOOGLERAAR IN DE FACULTEIT DER GODGELEERDHEID, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN DE SENAAT VAN DE UNIVERSITEIT IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP VRIJDAG 8 NOVEMBER 1957, DES NAMIDDAGS TE 16 UUR DOOR ANDREAS JOZEF JANSSEN GEBOREN TE VELDEN I957 N.V. DRUKKERIJ ERASMUS — LEDEBERG/GENT INHOUD TEN GELEIDE iv LIJST DER AFBEELDINGEN χ AFKORTINGEN xiv LITERATUURLIJST xv LIJST VAN TEKSTUITGAVEN VAN INSCHRIFTEN EN AUTEURS . xxvni INLEIDING ι HOOFDSTUK I HET TROPAION IN DE GRIEKSE EN ROMEINSE LITERATUUR 6 § i. Afleiding, betekenis en schrijfwijze van het woord . 6 § 2. Accent 8 § 3. Grammaticaal en stilistisch gebruik 9 I. In verbinding met een werkwoord A. Grieks . 9 B. Latijn ... 14 II. In verbinding met een naamval A. Grieks . 16 B. Latijn ... 17 Ш. In verbinding met een praepositie A. Grieks . 17 B. Latijn ... 18 IV. Letterlijk en figuurlijk gebruik A. Grieks . 19 B. Latijn ... 21 § 4. -

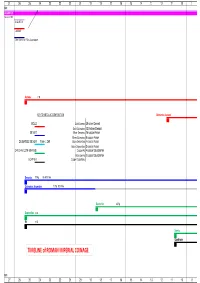

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

How 'Great' Was Alexander?

Historical Site of Mirhadi Hoseini http://m-hosseini.ir ……………………………………………………………………………………… IRANIAN HISTORY: POST-ACHAEMENIDS How ‘Great’ Was Alexander? By: Professor Ian Worthington1[1] (University of Missouri-Columbia) Why was Alexander II of Macedon called 'Great'? The answer seems relatively straightforward: from an early age he was an achiever, he conquered territories on a superhuman scale, he established an empire until his times unrivalled, and he died young, at the height of his power. Thus, at the youthful age of 20, in 336, he inherited the powerful empire of Macedon, which by then controlled Greece and had already started to make inroads into Asia. In 334 he invaded Persia, and within a decade he had defeated the Persians, subdued Egypt, and pushed on to Iran, Afghanistan and even India. As well as his vast conquests Alexander is credited with the spread of Greek culture and education in his empire, not to mention being responsible for the physical and cultural formation of the Hellenistic kingdoms — some would argue that the Hellenistic world was Alexander's legacy.[2[2]] He has also been viewed as a philosophical idealist, striving to create a unity of mankind by his so-called fusion of the races policy, in which he attempted to integrate Persians and Orientals into his administration and army. Thus, within a dozen years Alexander’s empire stretched from Greece in the west to India in the far east, and he was even worshipped as a god by many of his subjects while still alive. On the basis of his military conquests contemporary -

A Trip to Denizli

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY, SOUTHERN AEGEAN DEVELOPMENT AGENCY A TRIP TO DENİZLİ A TRIP TO DENİZLİ A TRIP TO A TRIP TO DENİZLİ Republic of Turkey (R.T.), Southern Aegean Development Agency Denizli Investment Support Office 2014 eparedAyşe Esin Başkan by: Now we are going to take a trip Denizli together…. Investment Support Office Coordinator Are you ready for a wonderful trip extending from 3rd Edition ancient cities to cotton travertine pools, from hot springs to thermal mud baths, from traditional weaving looms to historical places, from vineyards to the summit of the Aegean Region, from waterfalls each a natural wonder to legends, and from local folk songs to delicious dishes? ISBN No: 978-605-64988-1-7 All rights reserved. This work cannot be used either wholly or in part for processing, reproduction, distribution, copying, selling, leasing, lending, representing, offering, transmitting through wired/wireless systems or any other method, including digital and/or electronic media, without the prior written permission of the Southern Aegean Development Agency within the scope of legislation pertaining to intellectual and artistic works. The work may be cited on the condition that a reference to it is provided. References used in the work are provided at the end of the book. Cover Photo : Pamukkale Travertine Close-up Denizli Provincial Special Administration Archive - Mehmet Çakır A TRIP TO DENİZLİ 03 RUSSIA BULGARIA BLACK SEA GEORGIA İstanbul L. Edirne Kırklareli Atatürk Ereğli L. Bartın Sinop Tekirdağ Samsun Rize Artvin Zonguldak Kastamonu Trabzon Ardahan İstanbul İzmit Düzce Giresun S.Gökçen ARMENIA Sakarya Çankırı Amasya Ordu Yalova Bayburt Kars Bolu Çorum Tokat Bandırma L. -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

Bolivianismos En El Diccionario De La Lengua Española, 23ª. Ed (2014)

Bolivianismos en el Diccionario de la lengua española, 23ª. Ed (2014) 1551 lemas con la marca Bol. o la mención Bolivia o boliviano, na., en una o más acepciones. Autor: Raúl Rivadeneira Prada A __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ abajeño, ña. (De abajo). adj… ǁ 3. Arg., Bol., Ec., Méx., Nic., Perú y R. Dom. Natural o procedente de costas y tierras bajas. abalear. tr. Ant., Bol., Col., Ec., Méx., Nic., Pan., Perú y Ven. balear. abarrote. (De abarrotar). m… ο pl. 3. Am. Cen. Bol., Col., Ec., Méx. y R. Dom. Artículos comerciales, principalmente comestibles, de uso cotidiano y venta ordinaria. abarrotero, ra. m y f. Bol., Col., Ec. y Méx. Persona que tiene tienda o despacho de abarrotes. abatanado, da. (Del part. de abatanar). adj. 1. Arg., Bol., Chile, Ec., Méx., Par. y Perú. Dicho de un tejido: Muy compacto o de mucho cuerpo. abatanar. tr… ο prnl. 3. Bol. Dicho de un tejido: Desgastarse, apelmazarse por el uso o el lavado. abatatamiento. m. Arg., Bol. y Ur. Acción y efecto de abatatar o abatatarse. abatatar. (De batata). tr. Arg., Bol., Par. y Ur. Turbar, apocar, confundir. U.t.c. prnl. abigeato. (Del lat. abigeätus). m. Arg., Bol., Chile, Col., Ec., El Salv., Hond., Méx., Nic. Pan., Par., Perú y Ur. Hurto de ganado. abigeo. (Del lat. abigeus). m. Arg., Bol., Chile, Col., Ec., El Salv., Hond., Méx., Nic. Pan., Par., Perú y Ur. Ladrón de ganado. ablandar. tr... ǁ 5. Arg., Bol. y Uru. rodar (ǁ hacer que un automóvil marche a las velocidades prescritas). ablande. (De ablandar) m. Arg., Bol. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Daily Devotion Philippians

Daily Devotion reading, thinking, & praying through Philippians an Ipswich International Church publication Paul in Philippi From [Neapolis] we reached Philippi, a major city of that district of Macedonia and a Roman colony. And we stayed there several days. [Acts 16:12 (NLT)] Philippi was a town of Macedonia, in the territory of the Edones, on the confines of Thrace, and very near the northern extremity of the Aegean Sea. It was a little eastward of Mount Pangaeus, and about midway between Nicopolis on the east, and Thessalonica on the west. It was at first called Crenides, and afterwards Datus; but Philip, king of Macedonia and father of Alexander, having taken possession of it and fortified it, called it Philippi, after his own name. Julius Caesar planted a colony here, which was afterwards enlarged by Augustus; and hence the inhabitants were considered as freemen of Rome.1 The Gospel was preached first here by St. Paul. He had a vision in the night; a man of Macedonia appeared to him and said, “Come over to Macedonia and help us.” He was then at Troas in Mysia; from there he immediately sailed to Samothracia, came the next day to Neapolis, and thence to Philippi. There he continued for some time, and converted Lydia, a seller of purple, from Thyatira; and afterwards cast a demon out of a slave girl, for which he and Silas were persecuted, cast into prison, scourged, and put into the stocks: but the magistrates afterwards finding that they were Romans, took them out of prison and treated them civilly. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr.