PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMPERIAL EXEMPLA Military Prowess, Or Virtus, Is but One Quality That

CHAPTER FOUR IMPERIAL EXEMPLA Military prowess, or virtus, is but one quality that characterized an efffec- tive emperor. Ideally, a ‘good’ emperor was not just a competent general but also displayed other virtues. These imperial virtutes were propagated throughout the Roman Empire by means of imperial panegyric, decrees, inscriptions, biographies, and coins.1 On coinage in particular, juxtaposi- tions of AVG or AVGG with the virtue and/or the imperial portrait on the obverse would connect the virtues mentioned on the reverses directly with the emperor(s). Not all emperors emphasized the same virtues on their coinage. For example, Elagabalus seems not to have felt the need to stress virtus, whereas his successor Severus Alexander did try to convince the Roman people of his military prowess by propagating it on his coins. The presence or absence of particular virtues on coins issued by diffferent emperors brings us to the question as to whether an imperial canon of virtues existed. But before elaborating on this, the concept ‘virtue’ must be clarifijied.2 Modern scholars investigating imperial virtues on coinage consider vir- tues to be personifijications with divine power – in other words, deifijied abstractions or, as Fears puts it, ‘specifijic impersonal numina’.3 For many, the terms ‘personifijication’ and ‘virtue’ are interchangeable.4 Indeed, vir- tues can be considered personifijications. Yet, not all personifijications are 1 Noreña, “The communication of the emperor’s virtues”, p. 153. 2 ‘But if one is to compare coins with other sources, particularly philosopically inspired ones (i.e. in talking of the virtues of the ideal statesman) it is vital to distinguish what is a virtue and what is not’, A. -

Heads Or Tails

Heads or Tails Representation and Acceptance in Hadrian’s Imperial Coinage Name: Thomas van Erp Student number: S4501268 Course: Master’s Thesis Course code: (LET-GESM4300-2018-SCRSEM2-V) Supervisor: Mw. dr. E.E.J. Manders (Erika) 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 5 Figure 1: Proportions of Coin Types Hadrian ........................................................................ 5 Figure 2: Dynastic Representation in Comparison ................................................................ 5 Figure 3: Euergesia in Comparison ....................................................................................... 5 Figure 4: Virtues ..................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 5: Liberalitas in Comparison ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 6: Iustitias in Comparison ........................................................................................... 5 Figure 7: Military Representation in Comparison .................................................................. 5 Figure 8: Divine Association in Comparison ......................................................................... 5 Figure 9: Proportions of Coin Types Domitian ...................................................................... 5 Figure 10: Proportions of Coin Types Trajan ....................................................................... -

The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues Author(S): Carlos F

The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues Author(s): Carlos F. Noreña Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 91 (2001), pp. 146-168 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3184774 . Accessed: 01/09/2012 16:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies. http://www.jstor.org THE COMMUNICATION OF THE EMPEROR'S VIRTUES* By CARLOS F. NORENA The Roman emperor served a number of functions within the Roman state. The emperor's public image reflected this diversity. Triumphal processions and imposing state monuments such as Trajan's Column or the Arch of Septimius Severus celebrated the military exploits and martial glory of the emperor. Distributions of grain and coin, public buildings, and spectacle entertainments in the city of Rome all advertised the emperor's patronage of the urban plebs, while imperial rescripts posted in every corner of the Empire stood as so many witnesses to the emperor's conscientious administration of law and justice. -

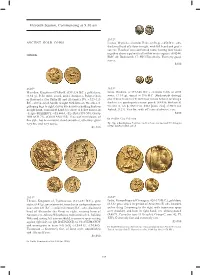

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

American Journal of Numismatics 26

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF NUMISMATICS 26 Second Series, continuing The American Numismatic Society Museum Notes THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY NEW YORK 2014 © 2014 The American Numismatic Society ISSN: 1053-8356 ISBN 978-0-89722-336-2 Printed in China Contents Editorial Committee v Jonathan Kagan. Notes on the Coinage of Mende 1 Evangeline Markou, Andreas Charalambous and Vasiliki Kassianidou. pXRF Analysis of Cypriot Gold Coins of the Classical Period 33 Panagiotis P. Iossif. The Last Seleucids in Phoenicia: Juggling Civic and Royal Identity 61 Elizabeth Wolfram Thill. The Emperor in Action: Group Scenes in Trajanic Coins and Monumental Reliefs 89 Florian Haymann The Hadrianic Silver Coinage of Aegeae (Cilicia) 143 Jack Nurpetlian. Damascene Tetradrachms of Caracalla 187 Dario Calomino. Bilingual Coins of Severus Alexander in the Eastern Provinces 199 Saúl Roll-Vélez. The Pre-reform CONCORDIA MILITVM Antoniniani of Maximianus: Their Problematic Attribution and Their Role in Diocletian’s Reform of the Coinage 223 Daniela Williams. Digging in the Archives: A Late Roman Coin Assemblage from the Synagogue at Ancient Ostia (Italy) 245 François de Callataÿ. How Poor are Current Bibliometrics in the Humanities? Numismatic Literature as a Case Study 275 Michael Fedorov. Early Mediaeval Chachian Coins with Trident-Shaped Tamghas, and Some Others 317 Antonino Crisà. An Eighteenth-Century Sicilian Coin Hoard from the Termini-Cerda Railway Construction Site (Palermo, 1869) 339 Review Articles 363 American Journal of Numismatics Andrew R. Meadows Oliver D. Hoover Editor Managing Editor Editorial Committee John W. Adams John H. Kroll Boston, Massachusetts Oxford, England Jere L. Bacharach Eric P. Newman University of Washington St. -

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan Dynasty Owe Its Downfall to Its Ultimate Failure to Live up to Its Own Militaristic Identity?

Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan dynasty owe its downfall to its ultimate failure to live up to its own militaristic identity? Exam Number: B043183 Master of Arts with Honours in Classical Studies Exam Number: B043183 1 Acknowledgements Warm thanks to Dr Matthew Hoskin for his keen supervision, and to Dr Alex Imrie for playing devil’s advocate and putting up with my daft questions. Thanks must also go to my family whose optimism and belief in my ability so often outweighs my own. Exam Number: B043183 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One – Living by the Sword 6 Chapter Two – Dying by the Sword 23 Chapter Three – Of Rocky Ground and Great Expectations 38 Conclusion 45 Bibliography 48 Word Count: 14,000 Exam Number: B043183 3 List of Illustrations Fig. 1. Chart detailing the percentage of military coin types promoted by emperors from Pertinax to Numerian inclusive (Source: Manders, E. (2012), Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, AD 193-284, Leiden, p. 65, fig. 17). Fig. 2. Portrait statue showing Caracalla in full military guise (Source: https://www.dailysabah.com/history/2016/08/02/worlds-only-single-piece-2nd-century- caracalla-statue-discovered-in-southern-turkey (Accessed 14/01/17). Fig. 3. Bust of Caracalla wearing sword strap and paludamentum (Source: Leander Touati, A.M. (1991), ‘Portrait and historical relief. Some remarks on the meaning of Caracalla’s sole ruler portrait’, in A.M. Leander Touati, E. Rystedt, and O. Wikander (eds.), Munusula Romana, Stockholm, 117-31, p. -

Download (2MB)

Cunningham, Graeme James (2018) Law, rhetoric, and science: historical narratives in Roman law. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/41030/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Law, Rhetoric, and Science: Historical Narratives in Roman Law. Graeme James Cunningham LL.B. (Hons.), LL.M., M.Litt. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. School of Law, College of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow. September 2018 Abstract. The consensus of scholarship has upheld the view that Roman law is an autonomous science. A legal system, which, due to its systematic, doctrinal principles, was able to maintain an inherent and isolated logic within the confines of its own disciplinary boundaries, excluding extra-legal influence. The establishment of legal science supposedly took place in the late second to early first century BC, when the famed Roman jurist, Quintus Mucius Scaevola pontifex, is supposed to have first treated law in a scientific way under the guidance of Greek categorical thought. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

APOLLO in ASIA MINOR and in the APOCALYPSE Abstract

Title: CHAOS AND CLAIRVOYANCE: APOLLO IN ASIA MINOR AND IN THE APOCALYPSE Abstract: In the Apocalypse interpreters acknowledge several overt references to Apollo. Although one or two Apollo references have received consistent attention, no one has provided a sustained consideration of the references as a whole and why they are there. In fact, Apollo is more present across the Apocalypse than has been recognized. Typically, interpreters regard these overt instances as slights against the emperor. However, this view does not properly consider the Jewish/Christian perception of pagan gods as actual demons, Apollo’s role and prominence in the religion of Asia Minor, or the complexity of Apollo’s role in imperial propaganda and its influence where Greek religion was well-established. Using Critical Spatiality and Social Memory Theory, this study provides a more comprehensive religious interpretation of the presence of Apollo in the Apocalypse. I conclude that John progressively inverts popular religious and imperial conceptions of Apollo, portraying him as an agent of chaos and the Dragon. John strips Apollo of his positive associations, while assigning those to Christ. Additionally, John’s depiction of the god contributes to the invective against the Dragon and thus plays an important role to shape the social identity of the Christian audience away from the Dragon, the empire, and pagan religion and rather toward the one true God and the Lamb who conquers all. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY CHAOS AND CLAIRVOYANCE: APOLLO IN ASIA MINOR AND IN THE APOCALYPSE SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIBLICAL STUDIES BY ANDREW J. -

Handling of Facts and Strategy in Cicero's Speech In

Handling of Facts and Strategy in Cicero’s Speech in Defence of King Deiotarus Tamás NÓTÁRI Károli Gáspár University, Budapest / Faculty of Law and Political Science [email protected] ABSTR A CT : The three orationes Caesarianae, i.e., Pro Marcello and Pro Lig ario given in 46 and Pro rege Deiotaro delivered in 45 are connected by the fact that the addressee of all of them is Caesar. The speech made in defence of King Deiotarus is the fruit (if possible) of both a legally and rhetorically critical situation: the judge of the case is identical with the injured party of the act brought as a charge: Caesar. Thus, the proceedings, conducted in the absence of the accused, in which eventually no judgment was passed, should be considered a manifestation of Caesar’s arrogance, who made mockery of the lawsuit, rather than a real action-at-law. This speech has outstanding significance both in terms of the lawyer’s/orator’s handling of the facts of the case under circumstances far from usual, and in the development of the relation between Cicero and Caesar. We can also observe some thoughts on the theory of the state framed by Cicero, the fight against Caesar’s dicta- torship gaining ground, for the sake of saving the order of the state of the Republic. KEY WORDS : Pro rege Deiotaro, Caesarianae orations, crimen maiestatis. RECIBIDO : 4 de mayo de 2012 • ACEPT A DO : 7 de enero de 2012. In November 45, Cicero delivered his statement of the defence before Julius Caesar in favour of King Deiotarus (Pro rege Deiotaro), who, just as Q. -

Romans on Parade: Representations of Romanness in the Triumph

ROMANS ON PARADE: REPRESENTATIONS OF ROMANNESS IN THE TRIUMPH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Amber D. Lunsford, B.A., M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor William Batstone Adviser Professor Victoria Wohl Department of Greek and Latin Copyright by Amber Dawn Lunsford 2004 ABSTRACT We find in the Roman triumph one of the most dazzling examples of the theme of spectacle in Roman culture. The triumph, though, was much more than a parade thrown in honor of a conquering general. Nearly every aspect of this tribute has the feel of theatricality. Even the fact that it was not voluntarily bestowed upon a general has characteristics of a spectacle. One must work to present oneself as worthy of a triumph in order to gain one; military victories alone are not enough. Looking at the machinations behind being granted a triumph may possibly lead to a better understanding of how important self-representation was to the Romans. The triumph itself is, quite obviously, a spectacle. However, within the triumph, smaller and more intricate spectacles are staged. The Roman audience, the captured people and spoils, and the triumphant general himself are all intermeshed into a complex web of spectacle and spectator. Not only is the triumph itself a spectacle of a victorious general, but it also contains sub-spectacles, which, when analyzed, may give us clues as to how the Romans looked upon non-Romans and, in turn, how they saw themselves in relation to others.