The Communication of the Emperor's Virtues Author(S): Carlos F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Curse Texts: Mediterranean Tradition and Local Diversity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Acta Ant. Hung. 57, 2017, 57–82 DOI: 10.1556/068.2017.57.1.5 DANIELA URBANOVÁ LATIN CURSE TEXTS: MEDITERRANEAN TRADITION AND LOCAL DIVERSITY Summary: There are altogether about six hundred Latin curse texts, most of which are inscribed on lead tablets. The extant Latin defixiones are attested from the 2nd cent. BCE to the end of the 4th and begin- ning of the 5th century. However, the number of extant tablets is certainly not final, which is clear from the new findings in Mainz recently published by Blänsdorf (2012, 34 tablets),1 the evidence found in the fountain dedicated to Anna Perenna in Rome 2012, (26 tablets and other inscribed magical items),2 or the new findings in Pannonia (Barta 2009).3 The curse tablets were addressed exclusively to the supernatural powers, so their authors usually hid them very well to be banished from the eyes of mortals; not to speak of the randomness of the archaeological findings. Thus, it can be assumed that the preserved defixiones are only a fragment of the overall ancient production. Remarkable diversities in cursing practice can be found when comparing the preserved defixiones from particular provinces of the Roman Empire and their specific features, as this contribution wants to show. Key words: Curses with their language, formulas, and content representing a particular Mediterranean tradi- tion documented in Greek, Latin, Egyptian Coptic, as well as Oscan curse tablets, Latin curse tablets, curse tax- onomy, specific features of curse tablets from Italy, Africa, Britannia, northern provinces of the Roman Empire There are about 1600 defixiones known today from the entire ancient world dated from the 5th century BCE up to the 5th century CE, which makes a whole millennium. -

IMPERIAL EXEMPLA Military Prowess, Or Virtus, Is but One Quality That

CHAPTER FOUR IMPERIAL EXEMPLA Military prowess, or virtus, is but one quality that characterized an efffec- tive emperor. Ideally, a ‘good’ emperor was not just a competent general but also displayed other virtues. These imperial virtutes were propagated throughout the Roman Empire by means of imperial panegyric, decrees, inscriptions, biographies, and coins.1 On coinage in particular, juxtaposi- tions of AVG or AVGG with the virtue and/or the imperial portrait on the obverse would connect the virtues mentioned on the reverses directly with the emperor(s). Not all emperors emphasized the same virtues on their coinage. For example, Elagabalus seems not to have felt the need to stress virtus, whereas his successor Severus Alexander did try to convince the Roman people of his military prowess by propagating it on his coins. The presence or absence of particular virtues on coins issued by diffferent emperors brings us to the question as to whether an imperial canon of virtues existed. But before elaborating on this, the concept ‘virtue’ must be clarifijied.2 Modern scholars investigating imperial virtues on coinage consider vir- tues to be personifijications with divine power – in other words, deifijied abstractions or, as Fears puts it, ‘specifijic impersonal numina’.3 For many, the terms ‘personifijication’ and ‘virtue’ are interchangeable.4 Indeed, vir- tues can be considered personifijications. Yet, not all personifijications are 1 Noreña, “The communication of the emperor’s virtues”, p. 153. 2 ‘But if one is to compare coins with other sources, particularly philosopically inspired ones (i.e. in talking of the virtues of the ideal statesman) it is vital to distinguish what is a virtue and what is not’, A. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, (), – at ); M

Offprint from OXFORDSTUDIES INANCIENT PHILOSOPHY EDITOR:BRADINWOOD VOLUMEXLV 3 MORALEDUCATIONAND THESPIRITEDPARTOFTHE SOULINPLATO’S LAWS JOSHUAWILBURN I the tripartite psychological theory of Plato’s Republic, the spir- ited part of the soul, or the thumoeides, is granted a prominent role in moral development: its ‘job’ in the soul is to support and de- fend the practical judgements issued by the reasoning part (par- ticularly against the deleterious influence of the appetitive part), and its effective carrying out of that job is identified with the vir- tue of courage ( –). Early moral education, consequently, is largely concerned with preparing the spirited part of the soul for this role as reason’s ‘ally’. In Plato’s later work the Laws, the the- ory of tripartition is never explicitly advocated: there is no mention of a division of the soul into parts, and hence no discussion of a ‘spirited’ part of the soul with a positive role to play in moral deve- lopment. Not only that, but some of the most conspicuous passages about spirited motivation in the text emphasize its negative impact on our psychology and behaviour. The spirited emotion of anger, for example, is identified as one of the primary causes of criminal behaviour ( ). All this has led many commentators to conclude that in the Laws Plato rejects the tripartite theory of the soul as we know it from the Republic and adopts a new psychological model in its place. Christopher Bobonich, for example, has argued that Plato abandoned the idea of a partitioned soul altogether in the Laws, opting instead for a unitary conception of the soul. -

Stoicism and the Virtue of Toleration

STOICISM AND THE VIRTUE OF TOLERATION John Lombardini1 Abstract: This article argues that the Stoics possessed a conception of toleration as a personal and social virtue. In contrast with previous scholarship, I argue that such a conception of toleration only emerges as a product of the novel conceptions of the vir- tue of endurance offered by Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. The first section provides a survey of the Stoic conception of endurance in order to demonstrate how the distinc- tive treatments of endurance in Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius merit classification of a conception of toleration; the second section offers a brief reconstruction of the argu- ments for toleration in the Meditations. Introduction In his history of the concept of toleration, Rainer Forst identifies its earliest articulation with the use of tolerantia in Stoic philosophy. Though the word tolerantia first occurs in Cicero, it is used to explicate Stoic doctrine. In the Paradoxa Stoicorum, Cicero identifies the tolerantia fortunae (the endurance of what befalls one) as a virtue characteristic of the sage, and connects it with a contempt for human affairs (rerum humanarum contemptione);2 in De Finibus, endurance (toleratio) is contrasted with Epicurus’ maxim that severe pain is brief while long-lasting pain is light as a truer method for dealing with pain.3 Seneca, in his Epistulae Morales, also identifies tolerantia as a virtue, defending it as such against those Stoics who maintain that a strong endurance (fortem tolerantiam) is undesirable, and linking it -

Heads Or Tails

Heads or Tails Representation and Acceptance in Hadrian’s Imperial Coinage Name: Thomas van Erp Student number: S4501268 Course: Master’s Thesis Course code: (LET-GESM4300-2018-SCRSEM2-V) Supervisor: Mw. dr. E.E.J. Manders (Erika) 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 5 Figure 1: Proportions of Coin Types Hadrian ........................................................................ 5 Figure 2: Dynastic Representation in Comparison ................................................................ 5 Figure 3: Euergesia in Comparison ....................................................................................... 5 Figure 4: Virtues ..................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 5: Liberalitas in Comparison ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 6: Iustitias in Comparison ........................................................................................... 5 Figure 7: Military Representation in Comparison .................................................................. 5 Figure 8: Divine Association in Comparison ......................................................................... 5 Figure 9: Proportions of Coin Types Domitian ...................................................................... 5 Figure 10: Proportions of Coin Types Trajan ....................................................................... -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

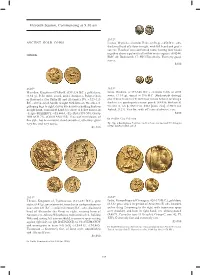

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

The Mythology of the Ara Pacis Augustae: Iconography and Symbolism of the Western Side

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 17–43 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.2 DAN-TUDOR IONESCU THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE: ICONOGRAPHY AND SYMBOLISM OF THE WESTERN SIDE Summary: The guiding idea of my article is to see the mythical and political ideology conveyed by the western side of the Ara Pacis Augustae in a (hopefully) new light. The Augustan ideology of power is in the modest opinion of the author intimately intertwined with the myths and legends concerning the Pri- mordia Romae. Augustus strove very hard to be seen by his contemporaries as the Novus Romulus and as the providential leader (fatalis dux, an expression loved by Augustan poetry) under the protection of the traditional Roman gods and especially of Apollo, the Greek god who has been early on adopted (and adapted) by Roman mythology and religion. Key words: Apollo, Ara, Augustus, Pax Augusta, Roma Aeterna, Saeculum Augustum, Victoria The aim of my communication is to describe and interpret the human figures that ap- pear on the external western upper frieze (e.g., on the two sides of the staircase) of the Ara Pacis Augustae, especially from a mythological and ideological (i.e., defined in the terms of Augustan political ideology) point of view. I have deliberately chosen to omit from my presentation the procession or gathering of human figures on both the Northern and on the Southern upper frieze of the outer wall of the Ara Pacis, since their relationship with the iconography of the Western and of the Eastern outer-upper friezes of this famous monument is indirect, although essential, at least in my humble opinion. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic.