Dying by the Sword: Did the Severan Dynasty Owe Its Downfall to Its Ultimate Failure to Live up to Its Own Militaristic Identity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Julio-Claudian Memory: the Vespasianic Building Program and the Representation of Imperial Power in Ancient Rome Joseph V

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department Spring 5-2-2014 Negotiating Julio-Claudian Memory: The Vespasianic Building Program and the Representation of Imperial Power in Ancient Rome Joseph V. Frankl Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Frankl, Joseph V., "Negotiating Julio-Claudian Memory: The eV spasianic Building Program and the Representation of Imperial Power in Ancient Rome" (2014). Classics Honors Projects. Paper 19. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/19 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Negotiating Julio-Claudian Memory: The Vespasianic Building Program and the Representation of Imperial Power in Ancient Rome By Joseph Frankl Advised by Professor Beth Severy-Hoven Macalester College Classics Department Submitted May 2, 2014 INTRODUCTION In 68 C.E., the Roman Emperor Nero died, marking the end of the Julio-Claudian imperial dynasty established by Augustus in 27 B.C.E (Suetonius, Nero 57.1). A year-long civil war ensued, concluding with the general Titus Flavius Vespasianus seizing power. Upon his succession, Vespasian faced several challenges to his legitimacy as emperor. Most importantly, Vespasian was not a member of the Julio-Claudian family, nor any noble Roman gens (Suetonius, Vespasian 1.1). -

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium*

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium* MELINDA SZEKELY Pliny the Elder writes the following about the king of Taprobane1 in the sixth book of his Natural History: "eligi regem a populo senecta clementiaque, liberos non ha- bentem, et, si postea gignat, abdicari, ne fiat hereditarium regnum."2 This account es- caped the attention of the majority of scholars who studied Pliny in spite of the fact that this sentence raises three interesting and debated questions: the election of the king, deposal of the king and the heredity of the monarchy. The issue con- cerning the account of Taprobane is that Pliny here - unlike other reports on the East - does not only use the works of former Greek and Roman authors, but he also makes a note of the account of the envoys from Ceylon arriving in Rome in the first century A. D. in his work.3 We cannot exclude the possibility that Pliny himself met the envoys though this assumption is not verifiable.4 First let us consider whether the form of rule described by Pliny really existed in Taprobane. We have several sources dealing with India indicating that the idea of that old and gentle king depicted in Pliny's sentence seems to be just the oppo- * The study was supported by OTKA grant No. T13034550. 1 Ancient name of Sri Lanka (until 1972, Ceylon). 2 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 89. Pliny, Natural History, Cambridge-London 1989, [19421], with an English translation by H. Rackham. 3 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 85-91. Concerning the Singhalese envoys cf. -

VIVERE MILITARE EST from Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I

VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I BELGRADE 2018 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY MONOGRAPHIES No. 68/1 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier VOM LU E I Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER PROOFREADING Institute of Archaeology Dave Calcutt Kneza Mihaila 35/IV Ranko Bugarski 11000 Belgrade Jelena Vitezović http://www.ai.ac.rs Tamara Rodwell-Jovanović [email protected] Rajka Marinković Tel. +381 11 2637-191 GRAPHIC DESIGN MONOGRAPHIES 68/1 Nemanja Mrđić EDITOR IN CHIEF PRINTED BY Miomir Korać DigitalArt Beograd Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade PRINTED IN EDITORS 500 copies Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade COVER PAGE Nemanja Mrđić Tabula Traiana, Iron Gate Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade REVIEWERS EDITORiaL BOARD Diliana Angelova, Departments of History of Art Bojan Ðurić, University of Ljubljana, Faculty and History Berkeley University, Berkeley; Vesna of Arts, Ljubljana; Cristian Gazdac, Faculty of Dimitrijević, Faculty of Philosophy, University History and Philosophy University of Cluj-Napoca of Belgrade, Belgrade; Erik Hrnčiarik, Faculty of and Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford; Philosophy and Arts, Trnava University, Trnava; Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Kristina Jelinčić Vučković, Institute of Archaeology, Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Zagreb; Mario Novak, Institute for Anthropological Ioan Piso, Faculty of History and Philosophy Research, -

Gods of Cultivation and Food Supply in the Imperial Iconography of Septimius Severus

Jussi Rantala a hundred years.1 The result of this was that a new emperor without any direct connection to the earlier dynasty had risen to the throne. This situation provided a tough challenge for Severus. He had to demonstrate that he was the true and legitimate emperor and he had to keep the empire and especially the capital calm Gods of Cultivation and Food after a period of crisis.2 The task was not made easier by the fact that Severus was not connected with the traditional elites of the capital; he can be considered an Supply in the Imperial Iconography outsider, for some scholars even an “alien”. of Septimius Severus Severus was a native of Lepcis Magna, North Africa. His “Africanness” has been a debated issue among modern researchers. Severus’ Punic roots are Jussi Rantala highlighted especially by Anthony Birley, and the emperor’s interest towards the cult of Serapis is also considered a sign of African identity.3 These ideas are University of Tampere nowadays somewhat disputed. Lepcis Magna was more or less Romanized long This article deals with the question of the role of gods involved with cultivation, grain before the birth of Severus, and the two families (the Fulvii and the Septimii) from and food supply in the Roman imperial iconography during the reign of Septimius which the family of Severus descended, were very much of Italian origin. Moreover, Severus. By evaluating numismatic and written evidence, as well as inscriptions, the the Severan interest in Serapis can hardly be considered an African feature: the article discusses which gods related to grain and cultivation received most attention same god was given attention already by Vespasian (who was definitely not an from Septimius Severus, and how their use helped the emperor to stabilize his rule. -

Herodian History of the Roman Empire Source 2: Aulus Gellius Attic

insulae: how the masses lived Fires Romans Romans in f cus One of the greatest risks of living in the densely populated city of Rome, and particularly in insulae was that of fires. Fires broke out easily (due to people cooking on open flames), spread easily (due to buildings being constructed out of wood, and buildings being built so closely together) and were hard to control. Several times large parts of the city went up in flames. It was not unusual for imperial funds to make good losses of impoverished wealthy citizens in the wake of a fire. Source 1: Herodian History of the Roman Empire In this passage from Herodian riots have broken out in the city of Rome, and soldiers combatting civilians started setting fire to houses. The soldiers did, however, set fire to houses that had wooden balconies (and there were many of this type in the city). Because a great number of houses were made chiefly of wood, the fire spread very rapidly and without a break throughout most of the city. Many men who lost their vast and magnificent properties, valuable for the large incomes they produced and for their expensive decorations, were reduced from wealth to poverty. A great many people died in the fire, unable to escape because the exits had been blocked by the flames. All the property of the wealthy was looted when the criminal and worthless elements in the city joined with the soldiers in plundering. And the part of Rome destroyed by fire was greater in extent than the largest intact city in the empire. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of ANCIENT ROME a Timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, Looking at the Successive Kings, Politicians, and Emperors Who Ruled Rome’S Expanding Empire

Rome: A Virtual Tour of the Ancient City A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANCIENT ROME A timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, looking at the successive kings, politicians, and emperors who ruled Rome’s expanding empire. 21st April, Rome's Romulus and Remus featured in legends of Rome's foundation; 753 BC mythological surviving accounts, differing in details, were left by Dionysius of foundation Halicarnassus, Livy, and Plutarch. Romulus and Remus were twin sons of the war god Mars, suckled and looked-after by a she-wolf after being thrown in the river Tiber by their great-uncle Amulius, the usurping king of Alba Longa, and drifting ashore. Raised after that by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife, the boys grew strong and were leaders of many daring adventures. Together they rose against Amulius, killed him, and founded their own city. They quarrelled over its site: Romulus killed Remus (who had preferred the Aventine) and founded his city, Rome, on the Palatine Hill. 753 – Reign of Kings From the reign of Romulus there were six subsequent kings from the 509 BC 8th until the mid-6th century BC. These kings are almost certainly legendary, but accounts of their reigns might contain broad historical truths. Roman monarchs were served by an advisory senate, but held supreme judicial, military, executive, and priestly power. The last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown and a republican constitution installed in his place. Ever afterwards Romans were suspicious of kingly authority - a fact that the later emperors had to bear in mind. 509 BC Formation of Tarquinius Superbus, the last king was expelled in 509 BC. -

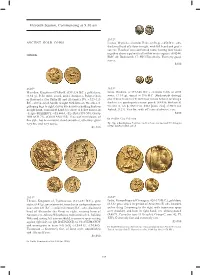

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Rachel Meyers Iowa State University, [email protected]

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2017 A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Rachel Meyers Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the History of Gender Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/130. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Abstract The ra ch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea was an important component in that town’s building activity. By situating the arch within its socio-historical context and acknowledging the political identity of Oea and nearby towns, this article shows that the arch at Oea far surpassed nearby contemporary arches in style, material, and execution. Further, this article demonstrates that the arch was a key element in Oea’s Roman identity. Finally, the article bridges disciplinary boundaries by bringing together art historical analysis with the concepts of euergetism, Roman civic status, and inter-city rivalry in the Roman Empire. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Idai.Publications Idai.Publications

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Sam Heijnen – Eric M. Moormann A Portrait Head of Severus Alexander in Delft aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue 1 • 2020 Umfang / Length § 1–9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34780/aa.v0i1.1017 • https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0048-aa.v0i1.1017.2 Zenon-ID: https://zenon.dainst.org/Record/002001103 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentralen Wissenschaftlichen Dienste | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter/ For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/index.php/aa/about ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 ©2020 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: https://www.dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Roman Empire Roman Empire

NON- FICTION UNABRIDGED Edward Gibbon THE Decline and Fall ––––––––––––– of the ––––––––––––– Roman Empire Read by David Timson Volum e I V CD 1 1 Chapter 37 10:00 2 Athanasius introduced into Rome... 10:06 3 Such rare and illustrious penitents were celebrated... 8:47 4 Pleasure and guilt are synonymous terms... 9:52 5 The lives of the primitive monks were consumed... 9:42 6 Among these heroes of the monastic life... 11:09 7 Their fiercer brethren, the formidable Visigoths... 10:35 8 The temper and understanding of the new proselytes... 8:33 Total time on CD 1: 78:49 CD 2 1 The passionate declarations of the Catholic... 9:40 2 VI. A new mode of conversion... 9:08 3 The example of fraud must excite suspicion... 9:14 4 His son and successor, Recared... 12:03 5 Chapter 38 10:07 6 The first exploit of Clovis was the defeat of Syagrius... 8:43 7 Till the thirtieth year of his age Clovis continued... 10:45 8 The kingdom of the Burgundians... 8:59 Total time on CD 2: 78:43 2 CD 3 1 A full chorus of perpetual psalmody... 11:18 2 Such is the empire of Fortune... 10:08 3 The Franks, or French, are the only people of Europe... 9:56 4 In the calm moments of legislation... 10:31 5 The silence of ancient and authentic testimony... 11:39 6 The general state and revolutions of France... 11:27 7 We are now qualified to despise the opposite... 13:38 Total time on CD 3: 78:42 CD 4 1 One of these legislative councils of Toledo..