ROMAN-CALENDARS.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Women's Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome

Gender & History ISSN 0953–5233 Judith Lynn Sebesta, ‘Women’s Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome’ Gender & History, Vol.9 No.3 November 1997, pp. 529–541. Women’s Costume and Feminine Civic Morality in Augustan Rome JUDITH LYNN SEBESTA Augustus was eager to revive the traditional dress of the Romans. One day in the Forum he saw a group of citizens dressed in dark garments and exclaimed indignantly, ‘Behold the masters of the world, the toga-clad race!’ He thereupon instructed the aediles that no Roman citizen was to enter the Forum, or even be in its vicinity, unless he were properly clad in a toga.1 In the terms of Augustan ideology, the avoidance of Roman dress by Romans was another sign of their abandoning the traditional Roman way of life, character and values in preference for the high culture, pomp, and moral and philosophical relativism of the Hellenistic East. This accultura- tion of foreign ways was frequently claimed to have brought Republican Rome to the edge of destruction in both the public and private spheres.2 Roman authors of the late first century BCE depict women in particular as devoted to their own selfish pleasure, marrying and divorcing at will, and preferring childlessness and abortion to raising a family. Such women were regarded as having abandoned their traditional role of custos domi (‘pre- server of the house/hold’), a role that correlated a wife’s body and her husband’s household. A Roman wife was expected to maintain her body’s inviolability and to preserve her husband’s possessions, while increasing his family by bearing children and enriching his wealth through her labors.3 The mindful care of the ideal wife was epitomized in the legendary story of the chaste Lucretia, who became an important symbol of wifehood in Augustan literature. -

Brutus, Cassius, Judas, and Cremutius Cordus: How

BRUTUS, CASSIUS, JUDAS, AND CREMUTIUS CORDUS: HOW SHIFTING PRECEDENTS ALLOWED THE LEX MAIESTATIS TO GROUP WRITERS WITH TRAITORS by Hunter Myers A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, Mississippi May 2018 Approved by ______________________________ Advisor: Professor Molly Pasco-Pranger ______________________________ Reader: Professor John Lobur ______________________________ Reader: Professor Steven Skultety © 2018 Hunter Ross Myers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Pasco-Pranger, For your wise advice and helpful guidance through the thesis process Dr. Lobur & Dr. Skultety, For your time reading my work My parents, Robin Myers and Tracy Myers For your calm nature and encouragement Sally-McDonnell Barksdale Honors College For an incredible undergraduate academic experience iii ABSTRACT In either 103 or 100 B.C., a concept known as Maiestas minuta populi Romani (diminution of the majesty of the Roman people) is invented by Saturninus to accompany charges of perduellio (treason). Just over a century later, this same law is used by Tiberius to criminalize behavior and speech that he found disrespectful. This thesis offers an answer to the question as to how the maiestas law evolved during the late republic and early empire to present the threat that it did to Tiberius’ political enemies. First, the application of Roman precedent in regards to judicial decisions will be examined, as it plays a guiding role in the transformation of the law. Next, I will discuss how the law was invented in the late republic, and increasingly used for autocratic purposes. The bulk of the thesis will focus on maiestas proceedings in Tacitus’ Annales, in which a total of ten men lose their lives. -

Nomina Animalium in Laterculus by Polemius Silvius

ARTYKUŁY FORUM TEOLOGICZNE XXI, 2020 ISSN 1641–1196 DOI: 10.31648/ft.6100 Maria Piechocka-Kłos* Faculty of Theology, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (Poland) NOMINA ANIMALIUM IN LATERCULUS BY POLEMIUS SILVIUS. THE BEGINNINGS OF THE LITURGICAL CALENDAR (5TH CENTURY) Abstract: Creating Laterculus, Polemus Silvius, a 5th-century author, was the first to attempt to integrate the traditional Roman Julian calendar containing the pagan celebrations and various anniversaries with new Christian feasts. Laterculus, as it should be remembered, is a work that bears the features of a liturgical calendar. In addition to dates and anniversaries related to religion and the state, the calendar contains several other lists and inventories, including a list of Roman provinces, names of animals, a list of buildings and topographical features of Rome, a breviary of Roman history, a register of animal sounds and a list of weights and sizes. Therefore, Laterculus, just like a traditional Roman calendar, was also used for didactic purposes. This paper aims to refer in detail to the zoological vocabulary, specifically the register of animal names and sounds included in this source. Laterculus contains in total over 450 words divided into six groups, including 108 words in the four-legged animal section, 131 in the bird section, 11 crustaceans, 26 words for snakes, 62 words for insects and 148 for fish. The sounds of animals, which are also included in one of the lists added to this calendar and titled Voces variae animancium, are also worth mentioning. A brief discussion on the history of the Roman calendar and the liturgical calendar certainly helps to present the issue referred to in the title to its fullest extent. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

On the Months (De Mensibus) (Lewiston, 2013)

John Lydus On the Months (De mensibus) Translated with introduction and annotations by Mischa Hooker 2nd edition (2017) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .......................................................................................... iv Introduction .............................................................................................. v On the Months: Book 1 ............................................................................... 1 On the Months: Book 2 ............................................................................ 17 On the Months: Book 3 ............................................................................ 33 On the Months: Book 4 January ......................................................................................... 55 February ....................................................................................... 76 March ............................................................................................. 85 April ............................................................................................ 109 May ............................................................................................. 123 June ............................................................................................ 134 July ............................................................................................. 140 August ........................................................................................ 147 September ................................................................................ -

West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Carly Maris September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Michele Salzman, Chairperson Dr. Denver Graninger Dr. Thomas Scanlon Copyright by Carly Maris 2019 The Dissertation of Carly Maris is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Thank you so much to the following people for your continued support: Dan (my love), Mom, Dad, the Bellums, Michele, Denver, Tom, Vanessa, Elizabeth, and the rest of my friends and family. I’d also like to thank the following entities for bringing me joy during my time in grad school: The Atomic Cherry Bombs, my cats Beowulf and Oberon, all the TV shows I watched and fandoms I joined, and my Twitter community. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and The Roman Triumph by Carly Maris Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in History University of California, Riverside, September 2019 Dr. Michele Salzman, Chairperson Parading Persia: West Asian Geopolitics and the Roman Triumph is an investigation into East-West tensions during the first 500 years of Roman expansion into West Asia. The dissertation is divided into three case studies that: (1) look at local inscriptions and historical accounts to explore how three individual Roman generals warring with the dominant Asian-Persian empires for control over the region negotiated -

Vespasian's Apotheosis

VESPASIAN’S APOTHEOSIS Andrew B. Gallia* In the study of the divinization of Roman emperors, a great deal depends upon the sequence of events. According to the model of consecratio proposed by Bickermann, apotheosis was supposed to be accomplished during the deceased emperor’s public funeral, after which the senate acknowledged what had transpired by decreeing appropriate honours for the new divus.1 Contradictory evidence has turned up in the Fasti Ostienses, however, which seem to indicate that both Marciana and Faustina were declared divae before their funerals took place.2 This suggests a shift * Published in The Classical Quarterly 69.1 (2019). 1 E. Bickermann, ‘Die römische Kaiserapotheosie’, in A. Wlosok (ed.), Römischer Kaiserkult (Darmstadt, 1978), 82-121, at 100-106 (= Archiv für ReligionswissenschaftW 27 [1929], 1-31, at 15-19); id., ‘Consecratio’, in W. den Boer (ed.), Le culte des souverains dans l’empire romain. Entretiens Hardt 19 (Geneva, 1973), 1-37, at 13-25. 2 L. Vidman, Fasti Ostienses (Prague, 19822), 48 J 39-43: IIII k. Septembr. | [Marciana Aug]usta excessit divaq(ue) cognominata. | [Eodem die Mati]dia Augusta cognominata. III | [non. Sept. Marc]iana Augusta funere censorio | [elata est.], 49 O 11-14: X[— k. Nov. Fausti]na Aug[usta excessit eodemq(ue) die a] | senatu diva app[ellata et s(enatus) c(onsultum) fact]um fun[ere censorio eam efferendam.] | Ludi et circenses [delati sunt. — i]dus N[ov. Faustina Augusta funere] | censorio elata e[st]. Against this interpretation of the Marciana fragment (as published by A. Degrassi, Inscr. It. 13.1 [1947], 201) see E. -

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De Dios Vela III, B.A. A Thesis In History Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Gary Edward Forsythe Chair of Committee Dr. John McDonald Howe Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School August, 2019 Copyright 2019, Juan De Dios Vela Texas Tech University, Juan De Dios Vela III, August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I: FOUNDATIONS..................................................................................... 13 Part one: Political Institutions ..................................................................................... 13 Part Two: Citizens, Latins, Colonies and the Social Web .................................... 23 Part Three: Magistrates and Local Control ........................................................... 26 Part Four: Patrons and Clients .................................................................................... 28 CHAPTER II: THE FIRST CRACKS ......................................................................... 32 The Gracchan Seditions ....................................................................................... 32 Impotent Interlopers ............................................................................................ -

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

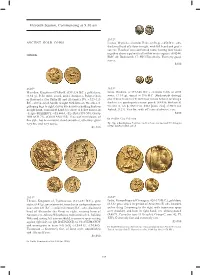

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt. -

Acta Histriae 28, 2020, 1

ACTA HISTRIAE 28, 2020, 1 UDK/UDC 94(05) ACTA HISTRIAE 28, 2020, 1, pp. 1-184 ISSN 1318-0185 UDK/UDC 94(05) ISSN 1318-0185 (Print) ISSN 2591-1767 (Online) Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko - Koper Società storica del Litorale - Capodistria ACTA HISTRIAE 28, 2020, 1 KOPER 2020 ACTA HISTRIAE • 28 • 2020 • 1 ISSN 1318-0185 (Tiskana izd.) UDK/UDC 94(05) Letnik 28, leto 2020, številka 1 ISSN 2591-1767 (Spletna izd.) Odgovorni urednik/ Direttore responsabile/ Darko Darovec Editor in Chief: Uredniški odbor/ Gorazd Bajc, Furio Bianco (IT), Stuart Carroll (UK), Angel Casals Martinez Comitato di redazione/ (ES), Alessandro Casellato (IT), Flavij Bonin, Dragica Čeč, Lovorka Čoralić Board of Editors: (HR), Darko Darovec, Lucien Faggion (FR), Marco Fincardi (IT), Darko Friš, Aleš Maver, Borut Klabjan, John Martin (USA), Robert Matijašić (HR), Darja Mihelič, Edward Muir (USA), Žiga Oman, Jože Pirjevec, Egon Pelikan, Luciano Pezzolo (IT), Claudio Povolo (IT), Marijan Premović (MNE), Luca Rossetto (IT), Vida Rožac Darovec, Andrej Studen, Marta Verginella, Salvator Žitko Uredniki/Redattori/ Editors: Urška Lampe, Gorazd Bajc, Arnela Abdić Gostujoča urednica/ Guest Editor: Katarina Keber Prevodi/Traduzioni/ Translations: Urška Lampe (slo.), Gorazd Bajc (it.), Petra Berlot (angl., it.) Lektorji/Supervisione/ Language Editor: Urška Lampe (angl., slo.), Gorazd Bajc (it.), Arnela Abdić (angl.) Izdajatelja/Editori/ Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko - Koper / Società storica del Litorale - Capodistria© Published by: / Inštitut IRRIS za raziskave, razvoj in strategije družbe, kulture in okolja / Institute IRRIS for Research, Development and Strategies of Society, Culture and Environment / Istituto IRRIS di ricerca, sviluppo e strategie della società, cultura e ambiente© Sedež/Sede/Address: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko, SI-6000 Koper-Capodistria, Garibaldijeva 18 / Via Garibaldi 18 e-mail: [email protected]; https://zdjp.si/ Tisk/Stampa/Print: Založništvo PADRE d.o.o.