Know the Ropes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolv Contents Climbing 03 Ultra Performance 05 Technical All-Around 09 All-Around 11 Adaptive 13 Rental 15 Performance Lifestyle 19 Accessories 23 Technology 27

SS 19 # EVOLV CONTENTS CLIMBING 03 ULTRA PERFORMANCE 05 TECHNICAL ALL-AROUND 09 ALL-AROUND 11 ADAPTIVE 13 RENTAL 15 PERFORMANCE LIFESTYLE 19 ACCESSORIES 23 TECHNOLOGY 27 FRONT COVER (TOP): DANIEL WOODS | JOSHUA TREE, CA | PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET MELISE EDWARDS | LEAVENWORTH, WA FRONT COVER (BOTTOM): LISA CHULICH | MALIBU, CA | PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET PHOTO: ANDREA SASSENRATH STEFAN MADEJ | POLISH JURA, POLAND PHOTO: MACIEK OSTROWSKI AUSTIN SARLES | GOLD BAR, WA PHOTO: NICOLE SARLES MEAGAN MARTIN | USAC BOULDERING NATIONALS CLIMBING PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET CLIMBING AGRO VEGAN FRIENDLY The ultimate high end bouldering shoe. With the sensitivity of a tensioned thin rubber midsole and maximum toe rubber coverage, the Agro has everything you’ll need to send your next project. Newly developed TPS (Tension Power System) technology pulls the forefoot from three different points into a downturned power position, thus maintaining the optimal curvature that often collapses over time on other no midsole shoes. The Dark Spine heel midsole supports and protects the heel and locks the foot into the shoe. The adjustable single pull closure system provides a supportive and powerful fit with an easy entry system and keeps buckles out of the way from aggressive toe hooks. Downturned asymmetric & down-camber profile | Synthetic (Synthratek VX) upper | Microfiber liner | TPS: tensioned rubber midsole, Dark Spine heel midsole | 4.2mm TRAX® SAS outsole | VTR rand (thicker front toe area) | Weight: 10 oz per shoe (size 9 US men’s) | Sizes: 5 - 13.5 US men’s (including half sizes) PHANTOM NEW | VEGAN FRIENDLY The Phantom climbing shoe is our pinnacle shoe designed by our R&D team in collaboration with our top athletes, Daniel Woods and Paul Robinson. -

La Sportiva Exum Ridge

Gear We’ve Tried Shoes for the Approach Four hybrid shoes offer extra grip for hikers who like to scramble water to get in. This shoe is ENSEN J the hands-down winner in EREK D the comfort department, though we weren’t thrilled with its durability. This shoe is a great choice for summer trail running, talus, and walking on granite slabs. Also available in a women’s model. By Allison Woods Scarpa Lite Climbing shoe manufacturers make a Ascent special type of hybrid shoe they call an La Sportiva’s Exum Ridge has a comfy fit, “approach shoe.” It’s a cross between a but doesn’t sport a lot of climbing traction. $159 light hiking boot, a trail runner and a www.scarpa-us.com climbing shoe. Approach shoes are great for hiking, especially if you’re La Sportiva Exum The Lite Ascent is a great-looking heading off-trail, crossing talus fields, Ridge shoe, and every time we wore them, climbing or scrambling. We’ve climbed people commented. More a low-top easy technical rock in them with no $90 boot than a hopped-up climbing shoe, problems. www.sportiva.com we liked the Lite Ascents for scram- Approach shoes are set apart from bling, and would not other trail shoes by a few traits you This very hesitate to bag a few won’t find in a trail runner or a hiking ENSEN peaks in them. The popular shoe felt J boot. The first thing you’ll notice is that great right out of EREK laces extend all the they have sticky rubber soles for extra the box. -

Safe Mountain Hiking Be in Good Health Plan and Prepare Carefully Mountain Walking Is an Endurance Sport

pull here ¨ 1 2 safe mountain hiking be in good health plan and prepare carefully Mountain walking is an endurance sport. It makes your heart and circulation Fit for mountain – endurance and strength Hiking maps, guide books, the internet and experts provide information on di- Rule of thumb for calculating walking time (for a medium-sized As an outdoor sport, hiking is a great way to get fit, work, so good health and an honest assessment of your capabilities are required. stances, altitude difference, difficulty and current conditions. Always tailor tours group of 4 to 6 people): Avoid having to rush and adopt a pace that keeps all members of your group from There are many ways to train for endurance: to the group! Pay particular attention to the weather forecast because rain, wind Allow 1 hour for every 300 m (ca 1000 ft) climbed. Allow 1 hour for meet people and have fun. The aim of the following getting out of breath. Walking, hiking, nordic walking, running, cycling, mountain biking, cardio training in and cold increase the risk of accidents. every 500 m (ca 1600 ft) descended. Allow 1 hours for every 4 km recommendations from the Alpine Associations is the gym, cross-country skiing, ski tours ... (ca 2,5 miles) walked. Facts Mountain hiking is not a walk in the park. Careful preparation is essential for safe to make hiking as safe and enjoyable as possible. Sudden cardiac death (heart attack) is the second most frequent cause of death (40 The training effect depends on regularity and the correct intensity: mountain hiking and protects you from unpleasant surprises. -

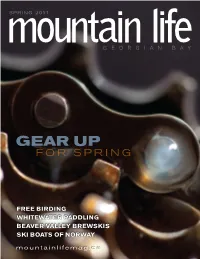

Gear up for Spring

SPRING 2 011 GEORGIAN BAY GEAR UP FOR SPRING FREE BIRDING WHITEWATER PADDLING BEAVER VALLEY BREWSKIS SKI BOATS OF NORWAY GEAR, LOCAL TRIPS, BIKE, HIKE & MORE mountainlifemag.ca mountainlifemag.ca CB 14912 Mountain Life FPG 10_Layout 1 11-03-07 11:07 AM Page 1 365 Different Ways To Enjoy Cobble Beach. Right At Your Doorstep. Home designs inspired by Cobble Beach’s extraordinary beauty. At Cobble Beach, golf is just one of the “above par” activities. Relax at our full-service spa, work-out in the fitness centre or take to the great outdoors for hiking, tennis, swimming in the plunge pool, boating, biking, skiing, skating and snowshoeing. Also in the master plan, an idyllic Village Centre with a café, a general store, an aquatic centre with an indoor pool, and a village green which will host seasonal events – all overlooking the majestic waterfront. The Elderslie The Kemble Resort homesites from $149,900. Residences from mid $300,000 to over $1 million. MODEL HOMES TO VIEW. $10 OFF NEXT ROUND OF GOLF USE PROMO CODE CB1108 NEXT TIME YOU BOOK A ROUND OF GOLF AT COBBLE BEACH (LIMIT 2 PER AD) 1.877.781.0149 cobblebeach.com Follow us on: Brokers Protected. Exclusive Listing PMA Brethour Realty Group Brokerage. Prices & specifications subject to change without notice. All rights reserved. E.&O.E. Live the Lifestyle MOUNTAINCROFT by Grandview Homes Collingwood’s most desired communities, Mountaincroft. your new home will put you in the centre of all the action. L IMITED TIME AMAZING BONUS PACKAGE OFFERS PACKAGE OFFERS! . You can own a brand new lifestyle property in one of Collingwood’s most desired communities, Mountaincroft. -

SUMMER MOUNTAINEERING EQUIPMENT LIST for Overnight Trips

SUMMER MOUNTAINEERING EQUIPMENT LIST For overnight trips FOOTWEAR: Objective dependent - check with MAG on the exact requirements for your trip ● Lightweight Mountaineering Boots: depending on the objective, they may need to accommodate a semi-automatic crampon. Be sure to break them in with some long hikes prior to your trip. (Guide’s Pick: Scarpa Zodiac Tech GTX) ● Approach Shoes: Sticky rubber hiking shoe for non-technical climbing. ● Rock Shoes: For technical rock climbing routes. Sticky rubber approach shoes are fine for moderate routes (i.e. Granite Peak in MT). Not necessary for Gannett Peak. ● Socks: 2 to 4 pairs (synthetic or wool-mix), sized for your boots. At least one thin liner is recommended for blister management. ● River Crossing Shoes: lightweight Crocs or Keens that can also double as a camp shoe NOTE: On Gannett Peak, some participants choose to have a hiking approach shoe for the majority of the hiking and only use the climbing boot on the day of our climb. This can be a good combination but obviously adds weight to your load. TOP LAYERS ● T-shirt/Sport Shirt: synthetic ● Long Sleeve Base Layer: synthetic or wool ● Fleece: medium-weight polar fleece ● Puffy Jacket: down or synthetic fill, light to medium-weight ● Rain Jacket: lightweight BOTTOM LAYERS ● Bottom Base Layer (long johns): lightweight synthetic or wool ● Climbing Pant: synthetic/nylon ● Hiking Short: synthetic ● Rain Pant: lightweight OTHER ● Gaiters: through mid-July (Guide’s pick: Black Diamond Talus or Cirque Gaiters) ● Hat or Visor: for sun ● Warm Hat: lightweight that fits under a helmet ● Gloves: light to mid-weight, with Gore-Tex shell ● Backpack: 60L-75L (Guide’s Pick: Osprey: Ariel or Aether Series) ● Summit Pack: 15-25L super lightweight ● Sleeping Bag: 15 degree (Guide’s Pick: Mountain Hardwear Phantom 15) ● Sleeping Pad: Closed-cell foam or Thermarest (as lightweight as possible) ● Tent (optional): MAG can supply tents but they are 4-season and made to last. -

The Alps Equipment List

The Alps Equipment List Clothing: Carry items that are breathable, allow flexibility, resist wind and water, and based on a layering system. Please confer with your guide about specific clothing combinations and/or if you have any questions regarding your gear. • Boots – Rigid synthetic or leather mountaineering boots. If Mt. Blanc is on your itinerary you will want to include a pair of insulated boots. • Approach shoes -A beefy pair of hikers for doing climbs on the non snowy side of the Chamonix valley. You might cross some small sections of snow in these, but you will also carry them in your pack on climbs. • Gaiters – Necessary for snow travel. Ankle high gaiters are recommended for the Alps. • Socks – Wool or synthetic. Avoid cotton. A single heavy weight pair is best. A pair of liners with a medium sock also works well. Bring a spare set. • Pants – Synthetic preferred. Pants made from Schoeler Fabric such as Patagonia’s “Alpine Guide” or “Simple Guide” pants are great options. • Long Underwear – Top and bottoms: Capilene or polypropylene recommended. • Lightweight shirt – A lightweight fleece (Patagonia’s R1) or wool shirt. • Jacket – Synthetic, pile or wool. Patagonia’s “puffball” or similar synthetic is a great option as its lighter, warmer and more packable than fleece. • Shell gear – Gore-tex parka with hood and pants as lightweight as possible. These will live in your pack for much of the trip. Side zips on your pants are nice for pulling on over boots. • Gloves– Two pairs: one insulated with shell, the other lightweight, such as a windstopper fleece or nordic ski glove with a leather palm. -

The Himalaya's First Via Ferrata Skaha Bluffs Climbing History New

TheVolume 49, ArêteSummer 2018 The Himalaya's First Via Ferrata Page 18 New Zealand Summer Guiding Page 24 Skaha Bluffs Climbing History Page 28 Maximizing the Practicum/ Mentor Experience Page 38 Contents Editorial It's a Crappy Job but Somebody Has to Do it! 32 President’s Perspective 4 Active Listening and The Interpersonal Gap 34 Tucker Talk 5 Maximizing the Practicum/Mentor Experience 38 News Gear Reviews Training and Assessment Program Update 6 Pieps Micro Avalanche Beacon Review 40 Technical Director’s Report 8 2019 G3 Alpinist Glide Skin Review 42 ACMG Partnership Update 10 Black Diamond ATC Pilot Review 44 ACMG Scholarship News 12 Member Updates Spotlight on ACMG Members Diapers and Vows 47 Jean-Philippe LeBlanc Wins Sylvie Marois Award 14 In Memory of Brian Greenwood 48 Beef Jerky & Waders —First One Day Link up of Changes in ACMG Membership 49 Theft and Gift Ice Climbs 16 ACMG Officers, Directors, Advisors, The Sky's Way—The Himalaya's First Via Ferrata 18 Staff and Committees 50 ACMG Member Photo Gallery 22 KONSEAL FL SHOE Features Gain traction with a technical New Zealand Summer Guiding 24 approach shoe designed for stability and comfort on fast Skaha Bluffs Climbing History 28 and light adventures in serious FIRE!! Is your Backcountry Lodge Prepared? 30 mountain terrain. The Arête “That's what's so amazing about climbing—it's not just a sport. It's a lifestyle, it's a way of being creative, of connecting with yourself and with nature.” Chris Sharma Editor-in-Chief: Shaun King Editorial Consultants: Mary Clayton, Peter Tucker, Marc Piché Editorial Policy The Arêteattempts to print every submission believed to be of interest to the ACMG membership including items that challenge the Association to examine its actions or direction. -

Spring/ Summer 2016 Ca Talog

SPRING/ SUMMER 2016 CATALOG FIVE TEN® | NORTH AMERICA FIVE TEN® | EUROPE P.O. BOX 7039 ADI-DASSLER-STR. 1 REDLANDS, CA 92375 91074 HERZOGENAURACH U.S.A. GERMANY TEL: 909.798.4222 TEL: +49.9132.84.8708 FAX: 909.798.5272 FAX: +49.9132.84.76460 EMAIL: [email protected] EMAIL: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 30 YEARS OF ROCK & ROLL 1 DEAN POTTER 3 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | QUANTUM 7 CLIMBING | AGGRESSIVE 9 CLIMBING | MODERATE 13 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | STONEMASTER 17 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | STONEMASTER—RENTAL 19 CLIMBING | NEUTRAL 21 MIKE LIBECKI 25 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | ACCESS 29 OUTDOOR | HIKING 31 OUTDOOR | APPROACH 35 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | EDDY 39 OUTDOOR | WATER 41 SAM HILL 43 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | SAM HILL 47 ALL MOUNTAIN | CLIPLESS 49 PRODUCT HIGHLIGHT | KESTREL LACE-UP 51 ALL MOUNTAIN | FLATS 53 GRAVITY | CLIPLESS 63 GRAVITY | FLAT 65 CASUAL | DIRT 69 STEALTH® RUBBER | COMPOUNDS 71 CLIMBING/ OUTDOOR/ WATER | LINE OVERVIEW 73 BIKE | LINE OVERVIEW 75 ACCESSORIES 77 GLOSSARY | SIZING 79 1997 2011 To increase power without weight or bulk, Five Tom Cruise again looks to Five Ten for help. Ten invents the Fishhook midsole allowing We make a new rubber and special shoes and climbers to stand on microscopic edges. gloves for him to use in Mission Impossible 3: Ghost Protocol. ROCK & ROLL 1998 Five Ten introduces the world to 2006 2012 the first (ever) women’s specific Sam Hill takes 1st place at UCI Mountain Bike Five Ten introduces Stealth® Mi6—a climbing shoe, the Diamond. Fred World Championships, Downhill - Rotorua, New revolutionary new rubber with Nicole establishes Radja, the Zealand. -

Download Gear List Rumdoodle

Summer 14er ascent (Rumdoodle Ridge). The gear on this list is required. If you have any questions about this list or the gear on it, please contact our office or your guide for advice. Mountain Chalet or Mountain Equipment Recycler here in Colorado Springs are great resources for knowledge and product selection. PPAS also rents most gear (not clothing) on this list. 719-368-9524 [email protected] Climbing gear: __*Climbing helmet. __*Climbing harness. __*Climbing shoes. __*Belay device. *Included, but please bring your gear if you own them. Footwear: __Lightweight hiking boot or approach shoe with sticky rubber for more technical routes. __Wool or synthetic socks. No cotton. __Liner sock. This is a personal preference, not required. Clothing (all to be wool or synthetic): __Base Layer, short sleeve and long sleeve top. __Hiking Pants, convertible pants ok but no shorts. Lightweight softshell pants are preferred for wind and water resistant & versatility. __Insulation Layer, top. Softshell again is recommended here. Fleece is ok but have no wind protection, so softshell is preferred. __Waterproof rain gear. Hardshell Jacket with hood. Hardshell Pants with full side zip so they can be put on without taking boots off. Headwear: __Synthetic or wool hat (beanie) __Buff or neck gaiter. I highly recommend buffs for their versatility. __Ball Cap or Visor, sun protection for your face. __Sunglasses with dark lens’ and wraparound sun and wind protection. Handwear: __Liner glove __Softshell glove, water and wind resistant. Other gear: __25-35L Backpack, make sure your gear fits in pack prior to course day. __(2)1L waterbottle, leakproof bottle like Nalgene works best. -

Amga Hosts First Annual Land Managers Conference

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Board of Directors, Staff, Newsletter Contributors 2 Executive Director Corner 3 President Corner 3 AMGA HOSTS FIRST ANNUAL LAND Land Use Article continued 4 Technical Director Update 5 MANAGERS CONFERENCE Guides Gear 6 Scholarship Programs 7 Boulder, CO - The AMGA hosted a Land Managers Conference on April 17th and 18th. In atten- Membership Corner 8 dance were representatives from the National Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Membership Form 9 Management, Eldorado Canyon State Park, Jefferson County, National Outdoor Leadership School, Merchandise Form 9 Jackson Hole Mountain Guides, the Access Fund, and the American Mountain Guides Association Program Update 10 (for a complete list of attendees please contact [email protected]). Program Schedule 10 Contributors & Corporate Partners 11 Conference attendees gathered from across the country to participate in this first annual event. On Saturday, guest speakers included Maura Longden from the National Park Service and Steve Muehlhauser from Eldorado Canyon State Park. Discussions were held in a round table format that encouraged open communication between all conference attendees. Topics included the use of fixed hardware policies on public lands, and how to create a climbing management plan, and using the ANNUAL MEETING and AMGA as a resource to facilitate discussion between land management agencies and guides. On Saturday, Steve Muelhlhauser led attendees on a tour of Eldorado Canyon State Park to wrap up a 25th Anniversary productive and enjoyable day. The dates are set for the 2004 AMGA Sunday's guest speakers included Shawn Tierney from the Access Fund and AMGA Board of Annual Meeting and 25th Anniversary Directors member Boots Ferguson from Holland & Hart Law Offices. -

What Is the Best Way to Begin Learning About Fashion, Trends, and Fashion Designers?

★ What is the best way to begin learning about fashion, trends, and fashion designers? Edit I know a bit, but not much. What are some ways to educate myself when it comes to fashion? Edit Comment • Share (1) • Options Follow Question Promote Question Related Questions • Fashion and Style : Apart from attending formal classes, what are some of the ways for someone interested in fashion designing to learn it as ... (continue) • Fashion and Style : How did the fashion trend of wearing white shoes/sneakers begin? • What's the best way of learning about the business behind the fashion industry? • Fashion and Style : What are the best ways for a new fashion designer to attract customers? • What are good ways to learn more about the fashion industry? More Related Questions Share Question Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Question Stats • Latest activity 11 Mar • This question has 1 monitor with 351833 topic followers. 4627 people have viewed this question. • 39 people are following this question. • 11 Answers Ask to Answer Yolanda Paez Charneco Add Bio • Make Anonymous Add your answer, or answer later. Kathryn Finney, "Oprah of the Internet" . One of the ... (more) 4 votes by Francisco Ceruti, Marie Stein, Unsah Malik, and Natasha Kazachenko Actually celebrities are usually the sign that a trend is nearing it's end and by the time most trends hit magazine like Vogue, they're on the way out. The best way to discover and follow fashion trends is to do one of three things: 1. Order a Subscription to Women's Wear Daily. This is the industry trade paper and has a lot of details on what's happen in fashion from both a trend and business level. -

MHW Moab Equipment List.Pub

CCClimbingClimbing Equipment List MOAB CCCanyoneeringCanyoneering Equipment List 40 L Daypack-Guide Pick Mountain What to expect while Canyoneering around Hardwear-Via Rapida 35 Moab: While hiking into area canyons, you will Low profile hydration pack (towers) run into an amazing desert environment that is Solid Approach Shoe- Guide Pick Salewa hot, sticky and scratchy one minute then at the Firetail or Alp Trainer next corner you are wet and involved in a high Rock Shoes- rentals available angle adventure. The following list is a recom- Light cotton Long sleeve shirt mendation of what to wear to be comfortable to Light wicking short sleeve shirt- Guide Pick enjoy your trip. Mountain Hardwear-Wicked Light Tee short Light long cotton pant for climbing – Guide Clothing for hiking in the Canyons pick Mountain Hardwear Chocklight Pant Quick Dry Short for approach 20 to 30 L Daypack-We carry special Long sleeve Sun shirt Canyoneering packs available for rent. Light rain/ wind jacket – Guide pick Moun- Long sleeve sun shirt tain Hardwear-Chocklight Jacket Solid Approach Shoe that is amphibious that can get wet and dry out or solid hik- On approach to towers & crags we recommend ing shoes plus solid water sandals. durable footwear to protect feet from sharp Socks for Hiking rocks and spiny plants. Quick dry /durable Quick dry pants/long shorts that offer shorts and shirts. On approach, a 30 to 40 L protection from the sun and spiny plants. backpack that is adequate for water, extra Light wicking short sleeve shirt- Guide clothes and climbing gear used for the day.