Bouldering for Beginners by David Flanagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

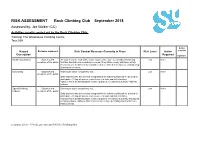

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

Mcofs Climbing Wall Specifications

THE MOUNTAINEERING COUNCIL OF SCOTLAND The Old Granary West Mill Street Perth PH1 5QP Tel: 01738 493 942 Website: www.mcofs.org.uk SCOTTISH CLIMBING WALLS: Appendix 3 Climbing Wall Facilities: Specifications 1. Climbing Wall Definitions 1.1 Type of Wall The MCofS recognises the need to develop the following types of climbing wall structure in Scotland. These can be combined together at a suitably sized site or developed as separate facilities (e.g. a dedicated bouldering venue). All walls should ideally be situated in a dedicated space or room so as not to clash with other sporting activities. They require unlimited access throughout the day / week (weekends and evenings till late are the most heavily used times). It is recommended that the type of wall design is specific to the requirements and that it is not possible to utilise one wall for all climbing disciplines (e.g. a lead wall cannot be used simultaneously for bouldering). For details of the design, development and management of walls the MCofS supports the recommendations in the “Climbing Walls Manual” (3rd Edition, 2008). 1.1.1. Bouldering walls General training walls with a duel function of allowing for the pursuit of physical excellence, as well as offering a relatively safe ‘solo’ climbing experience which is fun and perfect for a grass-roots introduction to climbing. There are two styles: indoor venues and outdoor venues to cater for the general public as a park or playground facility (Boulder Parks). Dedicated bouldering venues are particularly successful in urban areas* where local access to natural crags offering this style of climbing is not available. -

Too Important to Fail: the Problem of Aging Bolts Page 8

VERTICAL TIMES The National Publication of the Access Fund Winter 15/Volume 104 www.accessfund.org Too Important to Fail: The Problem of Aging Bolts page 8 SIX THINGS TO KNOW BEFORE YOU CLIMB IN THE DESERT 5 INSIDE SCOOP: INDIAN CREEK 6 CLIMBERS PARTNER WITH CITY TO OPEN NEW DULUTH ICE PARK 7 AF Perspective year ago, we shipped off several three-ring binders, each with over 500 pages of documents, to the Land Trust Alliance (LTA) Accreditation A Commission. This was our final application to become an accredited land trust—the culmination of six years of preparation that started with our adoption of the LTA standards in 2009. The accreditation process is so thorough that the LTA recommends hiring an external consultant just to help amass the necessary documentation. They generously awarded Access Fund a $2,500 grant to do just that. We’re very proud to announce that we are now one of 317 accredited land trusts in the United States. After launching our revolving loan program to support climbing area acquisitions in 2009, and after more than two decades of supporting land acquisitions across the country, we decided it was important for Access Fund to embody the highest standards for a land trust. Our work involves consulting with and supporting local climbing organizations (LCOs), and we want to give the best advice and serve as an example. LTA accreditation is important to us, to our network of local organizations, and to the climbing community. And it took a lot of work! We aren’t planning to throw ourselves an accreditation party, but I wanted to share a little of the backstory. -

2. the Climbing Gym Industry and Oslo Klatresenter As

Norwegian School of Economics Bergen, Spring 2021 Valuation of Oslo Klatresenter AS A fundamental analysis of a Norwegian climbing gym company Kristoffer Arne Adolfsen Supervisor: Tommy Stamland Master thesis, Economics and Business Administration, Financial Economics NORWEGIAN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS This thesis was written as a part of the Master of Science in Economics and Business Administration at NHH. Please note that neither the institution nor the examiners are responsible − through the approval of this thesis − for the theories and methods used, or results and conclusions drawn in this work. 2 Abstract The main goal of this master thesis is to estimate the intrinsic value of one share in Oslo Klatresenter AS as of the 2nd of May 2021. The fundamental valuation technique of adjusted present value was selected as the preferred valuation method. In addition, a relative valuation was performed to supplement the primary fundamental valuation. This thesis found that the climbing gym market in Oslo is likely to enjoy a significant growth rate in the coming years, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in sales volume of 6,76% from 2019 to 2033. From there, the market growth rate is assumed to have reached a steady-state of 3,50%. The period, however, starts with a reduced market size in 2020 and an expected low growth rate from 2020 to 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on this and an assumed new competing climbing gym opening at the beginning of 2026, OKS AS revenue is forecasted to grow with a CAGR of 4,60% from 2019 to 2033. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Evolv Contents Climbing 03 Ultra Performance 05 Technical All-Around 09 All-Around 11 Adaptive 13 Rental 15 Performance Lifestyle 19 Accessories 23 Technology 27

SS 19 # EVOLV CONTENTS CLIMBING 03 ULTRA PERFORMANCE 05 TECHNICAL ALL-AROUND 09 ALL-AROUND 11 ADAPTIVE 13 RENTAL 15 PERFORMANCE LIFESTYLE 19 ACCESSORIES 23 TECHNOLOGY 27 FRONT COVER (TOP): DANIEL WOODS | JOSHUA TREE, CA | PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET MELISE EDWARDS | LEAVENWORTH, WA FRONT COVER (BOTTOM): LISA CHULICH | MALIBU, CA | PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET PHOTO: ANDREA SASSENRATH STEFAN MADEJ | POLISH JURA, POLAND PHOTO: MACIEK OSTROWSKI AUSTIN SARLES | GOLD BAR, WA PHOTO: NICOLE SARLES MEAGAN MARTIN | USAC BOULDERING NATIONALS CLIMBING PHOTO: MATTHEW HULET CLIMBING AGRO VEGAN FRIENDLY The ultimate high end bouldering shoe. With the sensitivity of a tensioned thin rubber midsole and maximum toe rubber coverage, the Agro has everything you’ll need to send your next project. Newly developed TPS (Tension Power System) technology pulls the forefoot from three different points into a downturned power position, thus maintaining the optimal curvature that often collapses over time on other no midsole shoes. The Dark Spine heel midsole supports and protects the heel and locks the foot into the shoe. The adjustable single pull closure system provides a supportive and powerful fit with an easy entry system and keeps buckles out of the way from aggressive toe hooks. Downturned asymmetric & down-camber profile | Synthetic (Synthratek VX) upper | Microfiber liner | TPS: tensioned rubber midsole, Dark Spine heel midsole | 4.2mm TRAX® SAS outsole | VTR rand (thicker front toe area) | Weight: 10 oz per shoe (size 9 US men’s) | Sizes: 5 - 13.5 US men’s (including half sizes) PHANTOM NEW | VEGAN FRIENDLY The Phantom climbing shoe is our pinnacle shoe designed by our R&D team in collaboration with our top athletes, Daniel Woods and Paul Robinson. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

Multi-Pitch Trad Course

MULTI-PITCH TRAD COURSE This course is designed to teach the skills required to complete climb multi-pitch trad routes. Students will be given time and education to safely and efficiently lead multi-pitch climbs. Skills Covered Building of 3-point gear anchors Belaying a follower from the top with an auto-blocking device Swapping leads Being efficient on climbs including proper rope management Basic rescue techniques Understanding route selection Graduation Criteria Safely lead 1 multi-pitch trad route Prerequisites Single-pitch trad course or equivalent o Ability to lead on trad gear up to 5.6 o Ability to rappel safely o Ability to build a top-rope anchor on bolts o Basic skills to climb cracks Summary of Activities 1 evening kickoff session 2 evenings for skills review 2 weekend days of outdoor multi-pitch mock leading on trad gear 2 weekend days of outdoor multi-pitch leading on trad gear Student Gear List *Please DO NOT purchase gear until after our Kick Off Session (#17 & #18 are above what is required for the single-pitch course) 1. Climbing helmet 2. Rock climbing shoes 3. Harness 4. 1 personal anchor (Metolius) + locking carabiner 5. 6 single alpine slings 6. 2 double alpine slings 7. 1 triple alpine sling 8. 18 standard-sized non-locking carabiners (2 per sling) 9. 6 locking carabiners (in addition to the one in #4) 10. One set of standard-sized cams One cam each matching the following Black Diamond sizes: .3, .4, .5, .75, 1, 2, 3 11. 7 carabiners – one for each cam Do not need to be full sized Getting carabiners that match the color of your cams will be helpful 12. -

Ice Gear 2009 Gear Guide AUSTRIALPIN HU.GO

Ice Gear 2009 Gear Guide better swing control; the longer axes are good for glacier travel. Technical and mixed, curve- shafted tools fall in the 45-to-55cm range; size there to preference. Ice Gear Shaft. The classic mountain tool has a straight shaft, for anchor/boot-axe belays or WIth Ice clImbIng, as aid, upward progress allow you to switch out mono and dual front- walking-stick use. For steep ice, curved shafts relies almost directly on gear. Accordingly, ice points, too. offer better swing ‘n’ stick, knuckle protection, gear is highly specialized and typically falls bindings. The basic styles are strap-on, and clearance over bulges. into one of three categories: mountain use/ hybrid, and step-in. For mountain travel, strap- grip. A straight tool sans rubber grip is prefer- AUSTRIALPIN HU.GO glacier travel, waterfall- and pure-ice climbing, ons typically suffice and work with all boots; able for mountain use, where you’ll be posthol- With all the super-specialized ice or mixed climbing/dry tooling. hybrids require a sturdier boot with a heel ing through snow. For technical ice and mixed tools these days, it’s unusual to find welt; and step-ins fit stiffer boots with both use, a molded-rubber grip delivers purchase one so multipurpose — the Austri- Crampons heel and toe welts. and insulation against the shaft. Technical ice There are crampons for all types of climb- tools typically have pinky catches, for even Alpin (austrialpin.net) HU.go ing, from getting purchase on slick slopes to Ice Tools better grip. For hardcore ice and mixed, the Gear breaks the mold with a vari- inverted heel hooking. -

Bay Area Bouldering

Topo Excerpted From: Bay Area Bouldering The best guidebook for the Bay Area’s most classic problems. Available at the SuperTopo store: www.supertopo.com/topostore Bay Area Bouldering Bay Area Overview Map ������������� ���������� 5 � 99 � �� � ���������� �� � 101 ��������� �������� � ������� �� � ������ ���� 505 � � �� ��������� 80 � ���������� 1 �� ���������� 12 �� 80 �� ����� 101 12 ���� 50 ������ �� ��������� ��� 37 12 ��������� ������� 1 ��� ������ 80 5 99 �� �� �� �� �� �� ��� 80 ��������� �� ������� �������� 580 ������� 205 ����� 101 880 �� 99 280 1 �� �������� �� �� 101 9 5 17 �� ���������� ������ 152 5 ������� �������� 1 ������ �� 101 ��������� ���������� 4 B A Y A R E A BOULDERING: SUPERTOPOS Contents Introduction 9 East Bay/San Francisco When to Climb 9 Berkeley 90 Dining 10 Indian Rock 93 Bouldering Ratings 13 Mortar Rock 97 History 14 Little Yosemite 99 Remilard Park 99 North Coast Grizzly Peak 100 Salt Point 17 Glen Canyon 102 Fort Ross 18 Sea Crag 24 South Bay Twin Coves 25 Castle Rock 106 Super Slab 26 Castle Rock Boulders 112 River Mouth 30 Castle Rock Falls 115 Goat Rock 32 Goat/Billy Goat Rock 116 Pomo Canyon 40 Klinghoffers 117 Marshall Gulch 44 Indian Rock 119 Dillon Beach 45 Aquarian Valley 122 Skyline 128 North Bay Farm Hill 129 Stinson Beach 46 Panther Beach 130 Mickey’s Beach 52 Granite Creek 132 Ring Mountain 60 Mount Tamalpais 64 East of The Bay Marin Headlands 65 Rocklin 136 Squaw Rock 66 The Bar 137 Mossy Rock 67 Appendix Sugarloaf Ridge 68 More from SuperTopo 138 Putah Creek 76 About the Author 140 Vacaville 82 Index 141 5 FOR CURRENT ROUTE INFORMATION, VISIT WWW.SUPERTOPO.COM Warning. Climbing is an inherently dangerous sport in which severe injuries or death may occur. Relying on the information in this book may increase the danger. -

OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary Pursuits in the Outdoors Have Defined American Culture Since # Course Numbers with the # Symbol Included (E.G

University of New Hampshire 1 OUT 515 - History of Outdoor Pursuits in North America OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary pursuits in the outdoors have defined American culture since # Course numbers with the # symbol included (e.g. #400) have not the early 17th century. Over the past 400 years, activities in outdoor been taught in the last 3 years. recreation an education have reflected Americans' spiritual aspirations, imperial ambitions, social concerns, and demographic changes. This OUT 407B - Introduction to Outdoor Education & Leadership - Three course will give students the opportunity to learn how Americans' Season Experiences experiences in the outdoors have influenced and been influenced by Credits: 2 major historical developments of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th, and early An exploration of three-season adventure programs and career 21st centuries. This course is cross-listed with RMP 515. opportunities in the outdoor field. Students will be introduced to a variety Attributes: Historical Perspectives(Disc) of on-campus outdoor pursuits programming in spring, summer, and fall, Equivalent(s): KIN 515, RMP 515 including hiking, orienteering, climbing, and watersports. An emphasis on Grade Mode: Letter Grade experiential teaching and learning will help students understand essential OUT 539 - Artificial Climbing Wall Management elements in program planning, administration and risk management. You Credits: 2 will examine current trends in public participation in three-season outdoor The primary purpose of this course is an introduction -

Guidelines for a Quality Trail Experience

Guidelines for a Quality Trail Experience mountain bike trail guidelines January 2017 About BLM The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) may best be described as a small agency with a big mission: to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. It administers more public land – over 245 million surface acres – than any other federal agency in the United States. Most of this land is located in the 12 Western states, including Alaska. The BLM also manages 700 million acres of subsurface mineral estate throughout the nation. The BLM’s multiple-use mission, set forth in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, mandates that we manage public land resources for a variety of uses, such as energy development, livestock grazing, recreation, and timber harvesting, while protecting a wide array of natural, cultural, and historical resources, many of which are found in the BLM’s 27 million-acre National Landscape Conservation System. The conservation system includes 221 wilderness areas totaling 8.7 million acres, as well as 16 national monuments comprising 4.8 million acres. IMBA IMBA was founded in 1988 by a group of California mountain bike clubs concerned about the closure of trails to cyclists. These clubs believed that mountain biker education programs and innovative trail management solutions UJQWNF DG FGXGNQRGF CPF RTQOQVGF 9JKNG VJKU ƒTUV YCXG QH VJTGCVGPGF VTCKN access was concentrated in California, IMBA’s pioneers saw that crowded trails and trail user conflict were fast becoming worldwide recreation issues. This is why they chose “International Mountain Bicycling Association” as the organization’s name.