Bulletin POLISH NATIONAL COMMISSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Glocal Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage: Local Communities, Researchers, States and UNESCO

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Glocal Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage: Local Communities, Researchers, States and UNESCO 7 -9 July 2017 Tokyo, Japan Center for Glocal Studies (CGS), Seijo University and International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacifi c Region (IRCI) Proceedings of the International Symposium on Glocal Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage: Local Communities, Researchers, States and UNESCO 7 -9 July 2017 Tokyo, Japan Center for Glocal Studies (CGS), Seijo University and International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacifi c Region (IRCI) Published by Center for Glocal Studies, Seijo University (CGS) Seijo 6-1-20, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 157-8511, Japan E-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.seijo.ac.jp/research/glocal-center/ and International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacifi c Region (IRCI) c/o Sakai City Museum, 2 Cho Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802 Japan E-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.irci.jp © Center for Glocal Studies, Seijo University (CGS) © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacifi c Region (IRCI) Published on 30 November, 2017 Contents Foreword Wataru IWAMOTO and Tomiyuki UESUGI ………………………………………………………ⅳ Welcome Remarks Junichi TOBE …………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Opening Remarks 1.Tomiyuki UESUGI ……………………………………………………………………………… 4 2 .Wataru IWAMOTO………………………………………………………………………………… 6 3.Tim CURTIS ……………………………………………………………………………………… -

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

The Concept of Self and the Other

Tel Aviv University The Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts Department of Theatre Studies The Realm of the Other: Jesters, Gods, and Aliens in Shadowplay Thesis Submitted for the Degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Chu Fa Ching Ebert Submitted to the Senate of Tel Aviv University April 2004 This thesis was supervised by Prof. Jacob Raz TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS................................................................................................vi INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 I. THE CONCEPT OF SELF AND THE OTHER.................................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 11 The Multiple Self .................................................................................................................... 12 Reversal Theory...................................................................................................................... 13 Contextual Theory ................................................................................................................. 14 Self in Cross‐Cultural Perspective ‐ The Concept of Jen................................................... 17 Self .......................................................................................................................................... -

Churches of Peace (Poland) Protestants Were Persecuted and Deprived of the Right and Possibility to Practise Their Faith

for his subjects. At that time Silesia was a part of the Catholic Habsburg monarchy. In most of the province Churches of Peace (Poland) Protestants were persecuted and deprived of the right and possibility to practise their faith. Through the agency of the No 1054 Lutheran king of Sweden, the Emperor finally allowed (1651–52) the erection of three churches, henceforth known as the Churches of Peace, in Silesian principalities under direct Habsburg rule in Glogow (Glogau), which ceased to exist in the 18th century, Jawor (Jauer), and Swidnica (Schweidnitz) in the south-west part of present-day Poland. The Emperor’s consent was, however, given upon conditions Identification that were difficult to comply with. The churches had to be built exclusively of perishable materials (wood and clay), Nomination Churches of Peace in Jawor and Swidnica located outside city walls, and built in a limited period of time. These restrictions, together with the need to provide Location Historic region of Silesia, Principality of adequate space for large crowds of worshippers, forced the Swidnica and Jawor architect, Albrecht von Sabisch (1610–88), a prominent master-builder and fortification designer active in Wroclaw, State Party Republic of Poland to implement pioneering constructional and architectural solutions of a scale and complexity unknown ever before or Date 30 June 2000 since in wooden architecture. The timber-framed structures of enormous scale and complexity were assembled. The Churches of Peace, as they are still called today, were to be as inconspicuous as possible in the townscape; they were to be the refuge of a legally disadvantaged and only reluctantly tolerated minority, whose role as outsiders Justification by State Party should be evident in the location of the churches outside The Churches of Peace in Jawor and Swidnica give the protective city walls. -

Towns in Poland” Series

holds the exclusive right to issue currency in the Republic of Poland. In addition to coins and notes for general circulation, TTownsowns inin PolandPoland the NBP issues collector coins and notes. Issuing collector items is an occasion to commemorate important historic figures and anniversaries, as well as to develop the interest of the public in Polish culture, science and tradition. Since 1996, the NBP has also been issuing occasional 2 złoty coins, In 2009, the NBP launched the issue struck in Nordic Gold, for general circulation. All coins and notes issued by the NBP of coins of the “Towns in Poland” series. are legal tender in Poland. The coin commemorating Warsaw Information on the issue schedule can be found at the www.nbp.pl/monety website. is the fifth one in the series. Collector coins issued by the NBP are sold exclusively at the Internet auctions held in the Kolekcjoner service at the following website: www.kolekcjoner.nbp.pl On 24 August 2010, the National Bank of Poland is putting into circulation a coin of the “Towns in Poland” series depicting Warsaw, with the face value of 2 złoty, struck in standard finish, in Nordic Gold. face value 2 zł • metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy •finish standard diameter 27.0 mm • weight 8.15 g • mintage (volume) 1,000,000 pcs Obverse: An image of the Eagle established as the State Emblem of the Republic of Poland. On the sides of the Eagle, the notation of the year of issue: 20-10. Below the Eagle, an inscription: ZŁ 2 ZŁ. In the rim, an inscription: RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA (Republic of Poland), preceded and followed by six pearls. -

Yama, Hoko, Yatai, Float Festivals in Japan

Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan UNESCO inscribed “Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan” on the representative list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity. A total of 33 float festivals from around Japan are included as a single entry on the UNESCO list, among them two previously inscribed festivals, the Gion Festival yamahoko parade and the Hitachi Furyumono, now part of the new listing. The Japanese government proposed the 33 float festivals not just because they are centuries-old traditions, but also for the role they play bringing together many members of the community and preserving the traditional crafts of carpentry, lacquer work and fabric dyeing. Much work by many people goes into making and maintaining, and preparing and parading the floats. Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida expressed his hope that more people would be interested in the various regions of Japan thanks to the inscription, explaining that while the 33 festivals of “Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan” share common features, they have their own character, displaying many kinds of attractions of their region. © JNTO© Q. Sawami/ Probably the best known of the festivals in the joint inscription prefecture. Many are covered in lanterns for evening parades is Kyoto’s Gion Festival [top right]. The highlight of the festival is such as the Chichibu Night Festival in Saitama prefecture. the yamahoko parade. Japanese festivals often have their The largest of Japan’s festival floats are the Dekayama (‘giant origins in communities’ attempts to placate the gods or ask for mountains’) of the Seihaku Festival in Nanao city, Ishikawa their blessings. -

The Jews of Poland We Are Dedicated to Making Your Experience Rich in Content and Superior in Comfort

A Program for the Museum of Jewish Heritage Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow The Jews of Poland We are dedicated to making your experience rich in content and superior in comfort. October 1–12, 2021 This unique travel program combines the expertise and resources of two organizations that cherish the traditions, achievements, and faith of Jewish communities – past and present – around the world. Jewish Heritage Travel and the Museum of Jewish Heritage are delighted to have the opportunity to share this rich, varied, and poignant history and culture with you on these select trips. We look forward to traveling with you. Program Overview Before World War II, Poland’s 3 million Jews represented one of the largest and most influential Jewish communities in the world. The diverse community included Hasidim, secular Jewish intellectuals, Yiddish writers, Zionists, and socialists. Recently, a world-class museum opened in Warsaw, devoted to what Jewish life and culture were like in Poland. Jewish festivals in Kraków and other parts of Poland attract tens of thousands of people each year. Additionally, several universities have opened Judaic studies departments that have nurtured graduate students who have published impressive publications, bringing to life important aspects of Poland’s astonishingly rich Jewish history and culture. Join us on what promises to be a meaningful and fascinating trip— beginning in Warsaw, where a highlight will be a guided tour of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, a museum that explores Poland’s 1,000-year Jewish history. Additionally, in Warsaw, we will visit sites including the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, the memorial of Mila 18, and the Umschlagplatz—the site from which Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Treblinka. -

Please Click Here

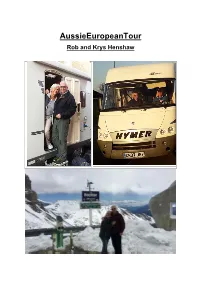

AussieEuropeanTour Rob and Krys Henshaw Contents Background Information ...................................................................... 16 Why have we written this document?............................................................................... 16 Who are we? ................................................................................................................... 18 Our Motorhome Research ............................................................................................... 18 What we thought we wanted based on our caravan experience in Australia .................... 19 Paying for a Motorhome in the UK from Australia ............................................................ 20 Registering and Insuring the Hymer in the UK ................................................................. 21 Insuring the Hymer 544 in the UK .................................................................................... 21 Schengen Zone Impications for Australians visiting Europe ............................................. 22 Our Schengen Zone Experience...................................................................................... 23 Fridge/Freezer Management in a Motorhome/Caravan:................................................... 25 The Challenges of Driving a Motorhome in Norway ......................................................... 27 Getting Maximum Life out of 12 Volt Batteries in a Motorhome/Caravan ......................... 33 Countries Visited .................................................................................. -

Proto-Micronesian Reconstructions—2

Proto-Micronesian Reconstructions—2 Byron W. Bender, Ward H. Goodenough, Frederick H. Jackson, Jeffrey C. Marck, Kenneth L. Rehg, Ho-min Sohn, Stephen Trussel, and Judith W. Wang university of hawai‘i and university of pennsylvania Part 1 (in volume 42 [1]) presents some 980 reconstructions for Proto-Micronesian, Proto–Central Micronesian, and Proto–Western Micronesian. Part 2 in this issue gives reconstructions for two additional subgroups within Proto-Micronesian: Proto- Pohnpeic (PPon) and Proto-Chuukic PCk), and for the larger group that they com- prise, Proto–Pohnpeic-Chuukic (PPC). A few putative loans are also identi²ed, and a finder list for all reconstructions is provided. PROTO–POHNPEIC-CHUUKIC (PPC) PPC *adoola ‘variety of sweet-husked coconut palm’: Chk atoon, ótoon; Pul yótool, yótoolá-(n); Crl atool; Wol atoole; PCk *adoola; Pon adool. Cf. Yap waqthoel, waqtoel, waq- tool ‘a type of tree’. PPC *-ali ‘strand, thin piece (counting classifier)’: Pul yaal ‘necklace, belt’, -el, -ál ‘s. or string (in counting)’; Crl áál, áli-(l) ‘s. of head hair, s. of’, -yál ‘long thin object such as string, hair (in counting)’; Wol yaali, yan-(ni)- ‘hair, thread, thin object, h. of’, -yali, -yeli ‘thin piece, sheet, or leaf (in counting)’; PuA yaani, yani- ‘s. of hair’, -yani ‘thin piece (in counting)’; PCk *yaali, yali-; Pon -„l ‘garland (in counting)’. PPC *aúrú ‘south’: Chk éér, éérú-(n) ‘s., in the s., s. of’, (notowa)-ar ‘southwest’, (éétiwé)- ér ‘southeast’, éwúr ‘spirit world in the s. or southern sky (source of bountiful fruit and ²sh)’; Mrt yéér; Pul éér, éérú-n ‘to be the southwind, be at the s., southwind, s. -

Historic Salt Mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia Zabytkowe Kopalnie Soli W Wieliczce I Bochni

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AGH (Akademia Górniczo-Hutnicza) University of Science and Technology: Journals Geoturystyka 4 (18) 2008: 61-70 Historic salt mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia Zabytkowe kopalnie soli w Wieliczce i Bochni Janusz Wiewiórka1, Józef Charkot2, Krzysztof Dudek3 & Małgorzata Gonera4 1 Retired geologist of the Wieliczka and Bochnia Salt Mines, Park Kingi 5, 32-020 Wieliczka 2 Cracow Saltworks Museum Wieliczka, Zamkowa 8, 32-020 Wieliczka, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection, AGH University of Science and Technology, Al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Kraków, e-mail: [email protected] 4 Nature Conservation Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Al. Mickiewicza 33, 31-120 Kraków, e-mail: [email protected] Kraków – Krakowskie Żupy Solne. W XVI wieku był to największy ośrodek produkcyjny w Polsce i jeden z największych w Europie. Wydobycie soli kamiennej zakończyło się w Bochni w 1990, a w Wieliczce Warszawa Wieliczka w 1996 roku. Obydwa złoża znajdują się w utworach sfałdowanego Bochnia miocenu (baden – M4) jednostki zgłobickiej Karpat zewnętrznych. Seria solonośna składa się z formacji skawińskiej, wielickiej Dobczyce (ewaporaty) i warstw chodenickich. Złoże solne Wieliczki zbu- dowane jest z górnego złoża bryłowego i dolnego pokładowego. Kraków Myślenice Złoże bryłowe zostało utworzone w wyniku podmorskich spływów w południowej części basenu ewaporacyjnego. Obydwie części zło- Abstract: Historic salt mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia are situ- ża zostały ostatecznie uformowane w wyniku ruchów nasuwczych ated by the old trade road from Kraków to the east, in the region Karpat. -

A Feminist Critique of Knowledge Production

This volume is the result of the close collaboration between the University of Naples “L‘Orientale” and the scholars organizing and participating to the postgraduate course Feminisms in a Transnational Perspective in Dubrovnik, Croatia. It features 15 essays that envision a feminist critique of the production Università degli studi di Napoli of knowledge that contributes today, intentionally or not, to new “L’Orientale” forms of discrimination, hierarchy control, and exclusion. Opposing the skepticism towards the viability of Humanities and Social Sciences in the era of ‘banking education’, marketability, and the so-called technological rationalization, these essays inquiry into teaching practices of non- institutional education and activism. They practice methodological ‘diversions’ of feminist intervention A feminist critique into Black studies, Childhood studies, Heritage studies, Visual studies, and studies of Literature. of knowledge production They venture into different research possibilities such as queering Eurocentric archives and histories. Some authors readdress Monique production A feminist critique of knowledge Wittig’s thought on literature as the Trojan horse amidst academy’s walls, the war-machine whose ‘design and goal is to pulverize the old forms and formal conventions’. Others rely on the theoretical assumptions of minor transnationalism, deconstruction, edited by Deleuzian nomadic feminism, queer theory, women’s oral history, and Silvana Carotenuto, the theory of feminist sublime. Renata Jambrešic ´ Kirin What connects these engaged writings is the confidence in the ethics and Sandra Prlenda of art and decolonized knowledge as a powerful tool against cognitive capitalism and the increasing precarisation of human lives and working conditions that go hand in hand with the process of annihilating Humanities across Europe. -

BUNRAKU Puppet Theater Brings Old Japan to Life

For more detailed information on Japanese government policy and other such matters, see the following home pages. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website http://www.mofa.go.jp/ Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ BUNRAKU Puppet theater brings old Japan to life The puppet theater unraku is Japan’s professional puppet of the operators make the puppet characters stage B theater. Developed primarily in the 17th and their stories come alive on stage. The bunraku (puppet and 18th centuries, it is one of the four forms theater) stage is specially constructed of Japanese classical theater, the others being History of Bunraku to accommodate kabuki, noh, and kyogen. The term bunraku three-person puppets. The puppeteers operate comes from Bunraku-za, the name of the only Already in the Heian period (794–1185), from a pit behind a railing commercial bunraku theater to survive into at the front of the stage. itinerant puppeteers known as kugutsumawashi © Degami Minoru the modern era. Bunraku is also called ningyo traveled around Japan playing door-to- joruri, a name that points to its origins and door for donations. In this form of street essence. Ningyo means “doll” or “puppet,” entertainment, which continued up through and joruri is the name of a style of dramatic the Edo period, the puppeteer manipulated narrative chanting accompanied by the three- two hand puppets on a stage that consisted stringed shamisen. of a box suspended from his neck. A number Together with kabuki, bunraku developed of the kugutsumawashi are thought to have as part of the vibrant merchant culture of settled at Nishinomiya and on the island of the Edo period (1600–1868).