5 International Command and Control Research and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integration of Swedish and Dutch Forces in EU Naval Force Operation Atalanta, 2015

In 2015, the Netherlands and Sweden provided a joint contri- bution to the EU’s counter-piracy military mission EUNAVFOR Operation Atalanta. During their three-month deployment to the area of operation, Swedish troops and enablers – including two Combat Boat 90 assault craft and two AW109 helicopters – were stationed on board the Dutch warship HNLMS Johan de Witt, which also hosted the Force Headquarters (FHQ) led by a Swedish Admiral. This kind of cooperation, in particular having a tactical headquarters led by one nation and the fl agship led by another, was quite unique. In general, the integration was considered to have been suc- cessful – to some extent surprisingly so. This report describes and analyses the planning and execution of the fusion of Dutch and Swedish forces, identifying key lessons that may be of value in similar future collaborations. National regulations and procedures, command and control structures, preparatory training and exercises, the chosen level of integration and per- sonal mindsets are among the issues discussed. Bilateral Partnership on an Even Keel The Integration of Swedish and Dutch Forces in EU Naval Force Operation Atalanta, 2015 David Harriman and Kristina Zetterlund FOI-R--4101--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se September 2015 David Harriman and Kristina Zetterlund Bilateral Partnership on an Even Keel The Integration of Swedish and Dutch Forces in EU Naval Force Operation Atalanta, 2015 Bild/Cover: Mattias Nurmela, COMBATCAMERA, Swedish Armed Forces (Försvarsmakten) FOI-R--4101--SE Titel Bilateralt samarbete på rätt köl – Svenska och nederländska styrkors integrering i EU Naval Force Operation Atalanta, 2015 Title Bilateral Partnership on an Even Keel – The Integration of Swedish and Dutch Forces in EU Naval Force Operation Atalanta, 2015 Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4101--SE Månad/Month September Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 70 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet/Ministry of Defence Forskningsområde 8. -

Försvarsmaktens Gemensamma Identitet – Direktiv För Användandet Av Försvarsmaktens Namn, Profil Och Bild

Försvarsmaktens gemensamma identitet – direktiv för användandet av Försvarsmaktens namn, profil och bild Grafisk profil 2013 EN PROFIL. EN FÖRSVARSMAKT. Att ha en tydlig grafisk profil är viktigt för alla organisationer, så även för Försvarsmakten. Ett av de främsta skälen är att mot- tagaren måste förstå att det är Försvarsmakten som är avsändare. Utgångspunkten för vår grafiska profil är en Försvarsmakt med respekt och tilltro till organisationens mångfald, historia och tra- ditioner. Varje logotyp har sitt bestämda användningsområde och tillfälle. Vi måste redan i fred skapa förtroende kring vår förmåga till väpnad insats. En enhetlig grafisk profil som visar på fasthet och konsekvens bidrar på ett naturligt sätt till att betona detta. Därför ska den grafiska profilen tillämpas av alla i Försvarsmakten. Profilen kan naturligtvis inte vara heltäckande. Men den pekar ut en riktning och idé som ska efterlevas. Detta direktiv komplet- teras en gång om året. InFoS tar gärna emot synpunkter och önskemål om komplette- ringar av beskrivningar och mallar. Försvarsmaktens gemensamma identitet beslutas av informa- tionsdirektören. Kontrollera att du använder aktuell version via vårt intranät. Grafisk profil 2013 HKV 2013-09-16 • Version 1.3 • Bilaga 17 000:53923 INNEHÅLL FÖRSVARSMAKTENS HERALDISKA VAPEN........................................................................................................ 7 HErAlDiSKt vapen ....................................................................................................................................................................................8 -

An Adapted Version of the Concept Development Assessment Game Experiences from the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group Table-Top Discussion

An adapted version of the Concept Development Assessment Game Experiences from the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group Table-Top Discussion JENNIE GOZZI AND KARL SKOOG FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. The organisation employs approximately 1000 personnel of whom about 800 are scientists. This makes FOI Sweden’s largest research institute. FOI gives its customers access to leading-edge expertise in a large number of fi elds such as security policy studies, defence and security related analyses, the assessment of various types of threat, systems for control and management of crises, protection against and management of hazardous substances, IT security and the potential offered by new sensors. FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency Phone: +46 8 555 030 00 www.foi.se FOI-R--4083--SE SE-164 90 Stockholm Fax: +46 8 555 031 00 ISSN 1650-1942 May 2015 Jennie Gozzi and Karl Skoog An adapted version of the Concept Development Assessment Game Experiences from the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group Table-Top Discussion Bild/Cover: Försvarsmakten/Swedish Armed Forces FOI-R--4083--SE Titel En anpassad version av Concept Development Assessment Game Title An adapted version of the Concept Development Assessment Game Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4083--SE Månad/Month Maj/May Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 37 p Kund/Customer The Swedish Armed Forces / Försvarsmakten Forskningsområde 6. Metod- och utredningsstöd Projektnr/Project no E14503 (INS OA) E14508 (PROD STAB OA) Godkänd av/Approved by Maria Lignell-Jakobsson Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk. -

The Three Swords STAVANGER – NORWAY

THE THREE SWORDS STAVANGER – NORWAY Summer/Autumn 2011 The Three Swords Magazine 20/2011 1 THE THREE SWORDS STAVANGER – NORWAY Summer/Autumn – Issue No: 20 The Three Swords Front Cover _ Major General Jean Fred Berger photo by MSgt HERBERT BERGER, photo collage by BRANDON CHHOEUN Back Cover _ JWC’s World News Today (WNT) photo by CONTENTS INCI KUCUKAKSOY The Three Swords Magazine 20/2011 1 Flowers were Norway’s first and immediate 4 response to terror. Flowers in front of the Oslo Cathedral in the aftermath of the Oslo and Utøya Island tragedies. Photo by CDR (Sg) Helene Langeland, Royal Norwegian Navy, Chief PAO, Joint Warfare Centre. Unless mentioned otherwise, all photos in this magazine are by JWC Public Affairs Office. 2 The Three Swords Magazine 20/2011 The Three Swords CONTENTS Summer/Autumn 2011 • Issue No 20 26 5 Commander’s Foreword 6 JWC Change of Command by Inci Kucukaksoy 13 Remarks: Prof. Ole Lislerud PAX - Peace and the Art of War 14 An Interview with Major General Jean Fred Berger 18 Cyberspace: Implications for NATO 40 Operations and the Joint Warfare Centre by Lt Col Todd Waller 26 Hybrid Threat: Countering Hybrid Threat Experiment, May 2011, Talinn, Estonia by Adrian Williamson 34 Observations from OUP by Maj Martijn van der Meijs 40 ISAF TE 11/01 and Interviews By Inci Kucukaksoy 47 Exercise STEADFAST JOIST 11 47 By Lt Col Heiko Hermanns 50 Gender Dimension By Lone Kjelgaard 55 Making Your Idea Stick: Uses and Abuses of PowerPoint (Part III) By Paul Sewell 58 Neo-Taliban and Information Environment By Hope Carr 62 New Multimedia Capabilities at JWC By Pete and Laura Loflin DuBois 50 65 Press Desk Within JOC By RRC-FR PAO The Three Swords Magazine 20/2011 3 JWC Public Affairs Office PO Box 8080, Eikesetveien 4068 Stavanger, Norway Tel: +(47) 52 87 9130/9131/9132 Internet: www.jwc.nato.int FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, I am honoured and pleased to I choose to think that there are things we can do to protect our be back at the Joint Warfare democracies from acts of terror and I believe that what we are doing Centre. -

Reflections on Operational Analysis in Exercise COJA

FOI-R--0874--SE June 2003 ISSN 1650-1942 8VHUUHSRUW Henrik Moberg 5HIOHFWLRQVRQ2SHUDWLRQDO$QDO\VLVLQH[HUFLVH&2-$ Defence Analysis SE-172 90 Stockholm SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY FOI-R--0874--SE Defence Analysis June 2003 SE-172 90 Stockholm ISSN 1650-1942 8VHUUHSRUW Henrik Moberg Reflections on Operational Analysis in exercise COJA 03 ,VVXLQJRUJDQL]DWLRQ 5HSRUWQXPEHU,6515HSRUWW\SH FOI – Swedish Defence Research Agency FOI-R--0874--SE User report Defence Analysis 5HVHDUFKDUHDFRGH SE-172 90 Stockholm 2. Operational Research, Modelling and Simulation 0RQWK\HDU 3URMHFWQR June 2003 E1407 &XVWRPHUVFRGH 5. Commissioned Research 6XEDUHDFRGH 22 Operational Analysis and Support $XWKRUV HGLWRUV 3URMHFWPDQDJHU Henrik Moberg Henrik Moberg $SSURYHGE\ Elisabeth André-Turlind 6SRQVRULQJDJHQF\ Swedish Armed Forces 6FLHQWLILFDOO\DQGWHFKQLFDOO\UHVSRQVLEOH 5HSRUWWLWOH Reflections on Operational Analysis in exercise COJA 03 $EVWUDFW QRWPRUHWKDQZRUGV Co-operative Jaguar 2003 (COJA 03) was held at Karup Air Station in Denmark from the 24 March to the 4 April 2003. COJA 03 was a NATO/PfP Joint Combined Command Post Exercise (CPX). Sweden had 29 posts in the exercise including one civilian post in the OA-cell. The OA-cell in COJA 03 was organised as a part of the Command Group (CG), and so responsible to the Commander but was responsive and managed by the Chief of Staff (COS). The nature of many of the OA tasks makes it difficult to fit them in an exercise environment. Many tasks are progressive and would in a real mission be going on for a long time, e.g. data collecting and statistical surveys. In this respect the OA-cell should concentrate more on how to approach a problem, than to give a complete solution. -

Försvarsmaktens Årsredovisning 2006 Huvuddokument

Försvarsmakten Årsredovisning 2006 FOTO: FÖRSVARETS BILDBYRÅ / ANDREAS KARLSSON 107 85 Stockholm. Telefon: 08-788 75 00. Fax: 08-788 77 78. Webbplats: www.mil.se 2007-02-20 23 386: 63006 Försvarsmaktens ÅRSREDOVISNING 2006 Resultatredovisning, resultaträkning, balansräkning, an- slagsredovisning, finansieringsanalys och noter 2007-02-20 23 386: 63006 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING ÖVERBEFÄLHAVARENS KOMMENTAR.....................................................................................................1 OPERATIV FÖRMÅGA M.M............................................................................................................................ 4 UTGÅNGSPUNKTER FÖR REDOVISNINGEN............................................................................................................ 4 FÖRSVARSMAKTENS OPERATIVA FÖRMÅGA ........................................................................................................ 4 INSATSORGANISATIONEN .................................................................................................................................... 7 RESULTATREDOVISNING .............................................................................................................................. 9 LÄGET I GRUNDORGANISATIONEN....................................................................................................................... 9 UTBILDNING, PLANERING M.M. ......................................................................................................................... 11 MATERIEL, ANLÄGGNINGAR -

Interaction on the Edge : Proceedings from the 5Th GRASP

Johan Näslund & Stefan Jern (Editors) Since May 1998 Scandinavian group researchers and social psychologists have met bi-annually for what has to be called the GRASP conference. GRASP originally stood Interaction on the Edge for ”Group as Paradox”. The first four conferences were held in Linköping, Lund, Stockholm and Skövde respectively. Proceedings from the 5th GRASP conference, Linköping University, May 2006 The fifth conference was organized at Linköping University May 11-12, 2006 under the auspices of the FOG FORUM group. Generous assistance was given by the De- partment of Behavioural Sciences and the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskaps- rådet). This year’s theme was ”Interaction on the Edge” and a special emphasis was put on inter group processes. Sixty researchers from Sweden and Denmark took part INTERACTION ON THE EDGE and listened to thirty presentations. Twelve of these have been accepted for this proceeding volume. Johan Näslund & Stefan Jern (Editors) ISBN 978-91-85715-09-1 INTERACTION ON THE EDGE Johan Näslund & Stefan Jern (Editors) Interaction on the Edge Proceedings from the 5th GRASP conference, Linköping University, May 2006 ISBN 978-91-85715-09-1 Johan Näslund & Stefan Jern Interaction on the Edge, proceedings from the 5th GRASP conference, Linköping University, May 2006 © 2006 Författarna Grafisk form: Anna Bäcklin Lindén Omslagsbild: Johan Näslund Upplagans storlek: 130 Datum: April 2007 Tryck: LiU-Tryck, Linköpings universitet CONTENTS Interaction on the edge 7 Kjell Granström Effects of reward system on herding -

Air and Space Power Journal: May-June 2014

May–June 2014 Volume 28, No. 3 AFRP 10-1 Senior Leader Perspective Getting Our Partners Airborne ❙ 5 Training Air Advisors and Their Impact In-Theater Maj Gen Michael A. Keltz, USAF Features Joint Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance in Contested Airspace ❙ 29 Dr. Robert P. Haffa Jr. Anand Datla Nightfall ❙ 48 Machine Autonomy in Air-to-Air Combat Capt Michael W. Byrnes, USAF “Finnishing” the Force ❙ 76 Achieving True Flexibility for the Joint Force Commander Lt Col Matt J. Martin, USAF CDR Brian Rivera, USNR Maj Jussi Toivanen, Finnish Army The Air Force and Diversity ❙ 104 The Awkward Embrace Col Suzanne M. Streeter, USAF The Comanche and the Albatross ❙ 133 About Our Neck Was Hung Col Michael W. Pietrucha, USAF Religion in Military Society ❙ 157 Reconciling Establishment and Free Exercise Chaplain, Maj Robert A. Sugg, USAF 178 ❙ Book Reviews Cataclysm: General Hap Arnold and the Defeat of Japan . 178 Herman S. Wolk Reviewer: Jeff McGovern War over the Trenches: Air Power and the Western Front Campaigns, 1916–1918 . 180 E. R. Hooton Reviewer: Maj Steven J. Ayre, USAF Internal Security Services in Liberalizing States: Transitions, Turmoil, and (In)Security . 182 Joseph L. Derdzinski Reviewer: Nathan Albright Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II . 184 Arthur Herman Reviewer: Col John R. Culclasure, USAF, Retired Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation . 187 William F. Trimble Reviewer: Lt Col Dan Simonsen, USAF, Retired The Royal Air Force in Texas: Training British Pilots in Terrell during World War II . 189 Tom Killebrew Reviewer: Capt Walter J. -

Speaker Bios

BIOGRAPHY General Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army, Retired General Ham is the president and chief executive officer of the Association of the United States Army. He is an experienced leader who has led at every level from platoon to geographic combatant command. He is also a member of a very small group of Army senior leaders who have risen from private to four-star general. General Ham served as an enlisted infantryman in the 82nd Airborne Division before attending John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio. Graduating in 1976 as a distinguished military graduate, his service has taken him to Italy, Germany, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Macedonia, Qatar, Iraq and, uniquely among Army leaders, to over 40 African countries in addition to a number of diverse assignments within the United States. He commanded the First Infantry Division, the legendary Big Red One, before assuming duties as director for operations on the Joint Staff at the Pentagon where he oversaw all global operations. His first four-star command was as commanding general, U.S. Army Europe. Then in 2011, he became just the second commander of United States Africa Command where he led all U.S. military activities on the African continent ranging from combat operations in Libya to hostage rescue operations in Somalia as well as training and security assistance activities across 54 complex and diverse African nations. General Ham retired in June of 2013 after nearly 38 years of service. Immediately prior to joining the staff at AUSA, he served as the chairman of the National Commission on the Future of the Army, an eight-member panel tasked by the Congress with making recommendations on the size, force structure and capabilities of the Total Army. -

Defending Air Bases in an Age of Insurgency

AIR UNIVERSITY Defending Air Bases in an Age of Insurgency Shannon W. Caudill Colonel, USAF Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Caudill, Shannon W. Copy Editor Sandi Davis Defending air bases in an age of insurgency / Shannon W. Caudill, Colonel, USAF. Cover Art pages cm Daniel Armstrong Includes bibliographical references and index. Book Design and Illustrations ISBN 978-1-58566-241-8 L. Susan Fair 1. Air bases—Security measures—United States. 2. United States. Air Force—Security measures. Composition and Prepress Production 3. Irregular warfare—United States. I. Title. Vivian D. O’Neal UG634.49.C48 2014 Print Preparation and Distribution 358.4'14—dc23 Diane Clark 2014012026 Published by Air University Press in May 2014 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Disclaimer Editor in Chief Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed Oreste M. Johnson or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of Managing Editor the organizations with which they are associated or the Demorah Hayes views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, Design and Production Manager United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any Cheryl King other US government agency. This publication is cleared for public release and unlimited distribution. Air University Press 155 N. Twining St., Bldg. 693 Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 [email protected] http://aupress.au.af.mil/ http://afri.au.af.mil/ AFRI Air Force Research Institute ii This book is dedicated to all Airmen and their joint comrades who have served in harm’s way to defend air bases. -

Register of Graduates & Former Cadets Glossary of Abbreviations

Register of Graduates & Former Cadets Glossary of Abbreviations & Codes Indicates a direct ancestor or a direct descendent, or both, of another graduate * Indicates a Distinguished Cadet (order of merit) A–age/aged ABMC–American Battle Monuments Commission A–Appointed Abn–Airborne A–Armored AC–Army Air Corps A–Army AcadAffrs–Academic Affairs A–Assistant ACC–Army Communications Command A–Attaché Acct–Account/Accounting AA–Additional Appointee ACDA–Arms Control & Disarmament Agency AA–Anti-Aircraft (Artillery) ACDC–Army Combat Developments Command AA–Army Attaché ACE–Analysis and Control Element A&A–Astronomy & Astrophysics ACEMLF–Allied Command Europe Mobile Land Force AAA–Anti-Aircraft Artillery ACERT–Army Computer Emergency Response Team AAC–Anti-Aircraft Command ACJCS–Assistant to the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff AAC–Army Acquisition Corps ACLC–Aviation Center Logistics Command AAC&GMC–Anti-Aircraft and Guided Missile Center ACM–Afghanistan Campaign Medal AAC&GMS–Anti-Aircraft and Guided Missile School AcqPolDiv–Acquisition Policy Division AACS–Airways and Air Communications Service ACR–Armored Cavalry Regiment AAD–Air Assault Division AC/RC–Active Component/Reserve Component AADAC–Army Air Defense Artillery Center ACS–Air Commando Squadron AADC–Army Armament Development Center ACS–Assistant Chief of Staff AADC–Army Armament Development Command ACSAC–Assistant Chief of Staff for Automation & AAE–Aeronautical & Astronautics Engineer Communications AAF–Army Air Forces ACSC–Air Command & Staff College AAF–Army Airfield ACSCCIM–Assistant -

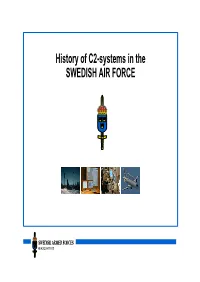

History of C2-Systems in the SWEDISH AIR FORCE

History of C2-systems in the SWEDISH AIR FORCE SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS Select timeframe: -47 48 - 56 57 - 65 66 - 71 72 - 80 81 - 92 93 - 00 01 - Select category: • C2 Systems • Military Radar • Hight Finders • ATS Radar • FV2000, Tactical loop • TDL SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS -47 48 - 56 57 - 65 66 - 71 72 - 80 81 - 92 93 - 00 01 - - 1947 J 22 23 Lbo • Human sensors • Army Air Surveillance Site • C2 Facilities • ”Stril 40” SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS Human sensors - 1947 • Optical surveillance • Reports to C2 by telephone • Army-organisation SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS Army Air Surveillance Site - 1947 • Mainly paperbased C2 • One Air Force Officer with authority to scramble squadron SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS C2 Facility - 1947 • SOC, Old type of Sector Operations Cell (Jaktcentral, jc) • Human sensor using radio (Jakt-ls) SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS ”Stril 40” - 1947 SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS -47 48 - 56 57 - 65 66 - 71 72 - 80 81 - 92 93 - 00 01 - ÖN4 1948 - 1956 ÖN2 ÖN3 ÖN1 N5 N3 N4 • The triggering factor… J 29 • Human sensors N1 N2 • Radar sensors O3 W4 • C2 Facilities W5 O2 • ”Stril 50” W3 O1 W2 G1 W1 S3 S2 S1 SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS The triggering factor… 1948 1956 June 13 1952 Swedish DC-3 was shot down over the Baltic Sea Three days later Swedish SAR Catalina also was shot down The triggering of Swedish Air Force QRA (Quick Readiness Alert) SWEDISH ARMED FORCES HEADQUARTERS Human Sensors 1948 1956 • Optical surveillance (Ls) (from 1948 organized by the Air Force) •