Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Frost

Patrick Elisa Wells And dear friend, Roberto Frost A Rose for Patrick.. Robert Frost Born Robert Lee Frost on March 26,1874 in San Francisco, California to William Prescott Frost Jr. Isabelle Moodie. His parents had Scottish and England descent. His father died in 1885, and he and his mother moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts under the patronage of Robert's grandfather. There his mother joined the Swedenborgian church where he was baptised, but he left the church in his adulthood. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892. It was there that he published his first poems, "La Noche Triste," and "The Song of the Wave," in the school's magazine. He then met and fell in love with fellow student Elinor Miriam White. The year of his graduation, he became engaged to Elinor. He attended Dartmouth College instead of Harvard because it was cheaper. He was there just long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. He was so bored by college life that he left at the end of his first semester. Frost tries to convince Elinor to marry him before returning to St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, but fails. After leaving college, he returned home to teach and to work at various jobs including delivering newspapers and factory labor. Truly not enjoying these jobs at all, he felt his true calling as a poet. A year later, he learns that The Independent will publish his poem "My Butterfly: An Elegy" and would pay him $15. He once again tried to convince Elinor to marry him at once. -

Phonological Features in Robert Frost's “Fire and Ice” and “Nothing Gold Can Stay” Poems

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PHONOLOGICAL FEATURES IN ROBERT FROST’S “FIRE AND ICE” AND “NOTHING GOLD CAN STAY” POEMS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By HADRIAN KUSUMA ASMARA Student Number: 144214071 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PHONOLOGICAL FEATURES IN ROBERT FROST’S “FIRE AND ICE” AND “NOTHING GOLD CAN STAY” POEMS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By HADRIAN KUSUMA ASMARA Student Number: 144214071 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI v PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vi PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Time is never Waiting For us To Do Something vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI This Page is dedicated for CHRISTIAN KUSUMA ASMARA viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to send my deepest gratefulness to Jesus Christ for all blessing during and after the process of writing this thesis. I thank Him because He has accompanied me through my family and my friends who always support me in every situation I have. Secondly, I would like to extend my gratitude to my thesis advisor, Arina Isti’anah, S.Pd., M.Hum., for understanding my diffculties, guiding me patiently, and supporting me in finishing my thesis. She patiently read my writing and gave me suggestions that made this writing a success. -

Tribhuvan University Relationship Between Humans and Nature In

Tribhuvan University Relationship between Humans and Nature in Selected Poems of Robert Frost A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English, Faculty of Humanities and Social ScienceRatnaRajyalaxmi Campus Exhibition Road, Kathmandu Partial Fulfillment of the Requirementfor the Degree of Master of Arts in English by ParbatiWagle TU Regd No: 6-1-38-675-97 Exam Roll No: 400198\2072 May 2018 Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitled, "Relationship between Humans and Nature in Selected Poems of Robert Frost" To my original work carried out as a Master's student at the Department of English at Ratna Rajya laxmi Campus excepted to the extent that assistance from others in the thesis's design and conception or in presentation style, and linguistic expression are duly acknowledged. All sources used for the thesis have been fully and properly cited. It contains no material with to a substantial extent has been accepted for the aWard of any other degree at Tribhuvan University or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis paper. _________________ Parbati Wagle May 2018 Tribhuvan University Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Department of English, Ratna Rajya laxmi Campus Letter of Approval This thesis entitled, "Relationship betWeen Humans and Nature in Robert Frost's Selected Poems" submitted to the Department of English, Ratna Rajya laxmi Campus, by Parbati Wagle has been approved by the undersigned members of the Research Committee, Members of Research Committee: ---------------------------- Prof. Dr. Anand Sharma Supervisor ---------------------- Pradip Adhikari External Examiner ---------------------- Pradip Sharma Head, Department of English Ratna Rajyalaxmi Campus May 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my thesis supervisor Prof. -

Translating Mimesis of Orality

Translating mimesis of orality: Robert Frost’s poetry in Catalan and Italian Marcello Giugliano TESI DOCTORAL UPF / ANY 2012 DIRECTORS DE LA TESI Dra. Victòria Alsina Dr. Dídac Pujol DEPARTAMENT DE TRADUCCIÓ I CIÈNCIES DEL LLENGUATGE Ai miei genitori Acknowledgements My first thank you goes to my supervisors, Dr. Victòria Alsina and Dr. Dídac Pujol. Their critical guidance, their insightful comments, their constant support and human understanding have provided me with the tools necessary to take on the numerous challenges of my research with enthusiasm. I would also like to thank Dr. Jenny Brumme for helping me to solve my many doubts on some theoretical issues during our long conversations, in which a smile and a humorous comment never failed. My special thanks are also for Dr. Luis Pegenaute, Dr. José Francisco Ruiz Casanova, and Dr. Patrick Zabalbeascoa for never hiding when they met me in the corridors of the faculty or never diverting their eyes in despair. Thank you for always being ready to give me recommendations and for patiently listening to my only subject of conversation during the last four years. During the project, I have had the privilege to make two research stays abroad. The first, in 2009, in Leuven, Belgium, at the Center for Translation Studies (CETRA), and the second in 2010 at the Translation Center of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, USA. I would like to give a heartfelt thank you to my tutors there, Dr. Reine Meylaerts and Dr. Maria Tymoczko respectively, for their tutoring and for offering me the chance to attend classes and seminars during my stay there, converting that period into a fruitful and exciting experience. -

Robert Frost As a Natural Poet Portrayed in His

ROBERT FROST AS A NATURAL POET PORTRAYED IN HIS SELECETED POEMS A THESIS BY : AFIAH ISWARA REG. NO. 130705105 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ROBERT FROST AS A NATURAL POET PORTRAYED IN HIS SELECETED POEMS A THESIS BY AFIAH ISWARA REG. NO. 130705105 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dr. Martha Pardede M.S Riko Andika Rahmat Pohan, S.S.,M.Hum NIP: 195212291 97903 2 001 NIP: 196801221 99803 2 001 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof.T.Silvana Sinar,MA.,Ph.D Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. NIP. 10540916 198003 2 003 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on Friday, November 16th, 2018 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Dr. Martha Pardede M.S Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. Dr. -

Robert Frost's Dantean Inspiration Elena Segarra Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2015 Dark Journeys: Robert Frost's Dantean Inspiration Elena Segarra Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Segarra, Elena, "Dark Journeys: Robert Frost's Dantean Inspiration" (2015). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 1021. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1021 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE DARK JOURNEYS: ROBERT FROST’S DANTEAN INSPIRATION SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR ROBERT FAGGEN AND DEAN NICHOLAS WARNER BY ELENA SEGARRA FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2014 DECEMBER 1, 2014 ! TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ROBERT FROST AND DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 CHAPTER ONE: LOSING THE ONE TRUE WAY 5 CHAPTER TWO: THE NATURE OF THE TRAVELER AND HIS JOURNEY 16 CHAPTER THREE: A VISION OF TRUTH 30 CONCLUSION: DWELLING IN DARKNESS 38 WORKS CITED 43 INTRODUCTION: ROBERT FROST AND DANTE ALIGHIERI In the play A Masque of Reason Robert Frost fabricates a conversation between Job and God, imagining that God used Job’s afflictions to teach man to submit to unreason (A Masque of Reason 379). According to Frost’s play, once people became aware of good and evil God “had to prosper good and punish evil” until Job’s miserable life demonstrated that “There’s no connection man can reason out / Between his just deserts and what he gets” (374). The God of A Masque of Reason has no desire to enforce justice. By exploring this concept of divinity, Frost calls into question the existence of any source of meaning and reason beyond what people can find on earth. -

On the Road with Robert Frost: His Poetry of Motion

On the Road with Robert Frost: His Poetry of Motion Robert Frost was a four time Pulitzer Prize winner, the most widely-read American poet of his time and one who for many readers became almost synonymous with the maples, birches, farms, fences, country roads, and snowdrifts of rural New England. Frost was also a Latin teacher, a chicken farmer, an amateur botanist, a shrewd creator of a self-reliant public persona, and one of the first poets to bring creative writing onto college campuses. Classes will focus on Frost’s use of voice and form in his lyrical, dramatic, and narrative poetry. Controversies regarding the poet’s biography, politics, and aesthetics will also be explored. No text required. Recommended: Robert Frost: Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays (Library of America, 1995) and Robert Frost, a Life, Jay Parini (Henry Holt & Company, 1999). Class 1: “A Peck of Gold” Frost’s early childhood and hard landing in New England. Remembering and transmuting his birthplace (“A Peck of Gold,” “Once By The Pacific,” “At Woodward Gardens”). Early and lifelong encounter with poetry via Palgrave’s Golden Treasury. Relentless pursuit of high school co-valedictorian Elinor White. Mental instability (The Dismal Swamp). Marriage. Children. Years in obscurity down on the farm (the danger of “launching out too soon”). Off to England. 1913 publication of A Boy’s Will (adjusted to provide an obeisance to A Shropshire Lad). Frost already “on the road” with physical, mental, metrical motion (“Into My Own,” “My November Guest,” “The Vantage Point”). Class 2: Back in the USA. American edition of A Boy’s Will (detaching his book from Housman). -

"Art That Hides Art": the Craft of Randall Thompson, Robert Frost, and Frostiana John C

"Art That Hides Art": The Craft of Randall Thompson, Robert Frost, and Frostiana John C. Hughes ince its first performance in 1959, Randall Robert Frost, whose poems serve as the text Thompson’sFrostiana has been a popular of Frostiana, suffers a similar fate. It is easy part of the American choral repertory. It to mistake the folksy, aesthetically accessible Scan be reasonably assumed that most choral nature of Thompson and Frost’s works for a lack conductors in the United States are at least of sophistication. Upon further examination, familiar with the piece. Many have performed however, one finds that these works are anything it, or portions thereof, either as a choir member but unrefined. Through craftsmanship and or conductor. The recent publications of a technical command, Frost and Thompson build documented catalogue of Thompson’s music layers of meaning beneath a deceptively simple and a single score containing all of Frostiana’s surface. Theirs is an “art that hides art.” movements demonstrate a continued interest in Thompson’s music and Frostiana in particular. 1 The following discussion will offer reasons why Thompson and Frost are dismissed as provincial Despite its popularity and rapid acceptance, or unsophisticated and then will propose a or perhaps because of its popularity and rapid reappraisal of their crafts. After a short history acceptance, Frostiana is deemed by some to of the composition of Frostiana, an examination be populist and is not necessarily considered 2 for College and University Choirs (Richard J. Bloesch and a sophisticated work of art. The poetry of Weyburn Wasson, American Choral Directors Association Monograph No. -

Imagining Boston: the Itc Y As Image and Experience Shaun O'connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 9 6-21-1986 Imagining Boston: The itC y as Image and Experience Shaun O'Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the American Literature Commons, United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation O'Connell, Shaun (1986) "Imagining Boston: The itC y as Image and Experience," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 2: Iss. 2, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol2/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New England Journal of Public Policy Imagining Boston: The City as Image and Experience Shaun O'Connell I think there are two ways in which place is known and cherished, two ways which may be complementary but which are just as likely to be antipathetic. One is lived, illiterate and unconscious, the other is learned, literate and conscious. In the literary sensibility, both are likely to co-exist in a conscious and unconscious tension: this tension and the poetry it produces are what I want to discuss. — Seamus Heaney, "The Sense of Place," in Preoccupations: Selected Prose 1968-1978 want to discuss community and imagery, social division and literary unity, I Boston poetry and prose. -

Robert Frost's World and Words

Welcome to Robert Frost's World and Words Professor Gary Bouchard A few years ago I developed a 100 level on-line summer course on Robert Frost for Saint Anselm students. To do so I teamed-up with talented videographer David Hjelm and traveled around New Hampshire to a few treasured locations from the poet’s life. Together we created a couple of dozen mini-lectures on Frost’s life and poems. In this peculiar time when we find ourselves in forced hibernation away from so many of the people and places we love, I wanted to do what I could to help lift you beyond your four walls into the world and imagination of one of New England and America’s most beloved poets. A unique figure in American poetry, Robert Frost is as complex as he is revered and mythologized. His voice and vision are inseparable from the New England landscape he inhabited, and his diction is as New Hampshire as granite ledge, birch trees, maple syrup, stone walls and accumulating snow. Most casual readers of poetry are acquainted with some of the more famous poems of Frost that are accessible to young readers. Beyond those dozen or so poems, Frost created a large body of work, including eight volumes of some of the most provocatively complex, metaphysical poems in American literature. Many of those poems are intricately connected to the landscapes, voices and imagination of New Hampshire. Together in this course we will travel on the road less taken. The lectures will bring you to his homes in Plymouth, Derry and Franconia, New Hampshire. -

Agustin Evin Wulandari 11320121 ENGLISH LETTERS and LANG

FIGURATIVE LANGUAGES USED IN ROBERT FROST’S SELECTED POEMS THESIS By: Agustin Evin Wulandari 11320121 ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF MALANG 2015 FIGURATIVE LANGUAGES USED IN ROBERT FROST’S SELECTED POEMS THESIS Presented to Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of SarjanaSastra (S.S.) By: Agustin Evin Wulandari NIM. 11320121 Advisor: Dra. Andarwati, M.A ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF MALANG 2015 i ii STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY Herewith, I Name : Agustin Evin Wulandari ID : 11320121 Faculty : Humanities Department : English Letters and Language Certify that the thesis written to fulfill the requirement for the degree of Sarjana Sastra (S1) entitled FIGURATIVE LANGUAGES USED IN ROBERT FROST’S SELECTED POEMS is truly my original work. It does not incorporate any materials previously written or publis by another person, except those indicates in questions and bibliography. Due to the fact, I am the only person responsible for the thesis if there is any objection or claim from others. Malang, 23 November 2015 The Writer, Agustin Evin Wulandari iii MOTTO “The dream is not to be spoken but to be proven” -Agustin Evin Wulandari- iv DEDICATION This thesis is proudly dedicated to my beloved parents, my late father Susilo Prayitno and my mother Kusmini, my lovely sibling Ketut Agni Susilo, Erna Indri Astutik, Ratna Idha Indrastiwi, Ivan Adi Supranjani, my sister in law Titin, my cute cousins Saylendra Agni Setia Bayu and Syahyudi Agni Bathara, my uncle Kardjito and family for their support, pray, love and everything. -

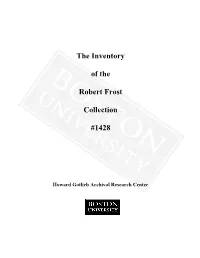

The Inventory of the Robert Frost Collection #1428

The Inventory of the Robert Frost Collection #1428 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center , . , ,:· ,, , I RICHARDS-FROST ROOM Robert Frost Inventory ~~aoc Gift of Paul C. Richards 1975- Outline of Inventory Box 1 I. }1Af.i7JSCRIPTS BY RF A. Notebooks 1. 1911-1912 (slipcase) 2. 1950 (slipcase) B. Poetry 1. "De.aeon's Child," 19 38 (slipcase) 2. "Discovery of the Madeiras," 1942 (slipcase) '3. 11 :!c1sque of Nercy, 11 1947 4. Individual Poems C, Prose II. MANUSCRIPTS RELATED TO RF III. LETTERS FROM RF AND FAMILY AND FRIENDS (See also section VE) Box 2 A. To Various Persons, 1913-1961 B. To Marie A. Hodge, 1913-1916 (slipcase) c. To Loring Holmes Dodd, 1921-1936 (slipcase) Hox 3 D. To Wade Van Dore, 1922-1961 (slipcase) Box 4 E. To WadB Van Dore from -Elinor, Carol and Lesley Frost (slipcase) F. Wade Van Dore Frostiana, 1927-;;;;.'1962(slipcase) Box 7 IV. GUEST BOOK OF HALLIE PHILLIPS GILCHRIST with inscription by RF, 1921 Box 5 V. PHOTOGRAPHS AND FRMIED ITEMS A. RF Alone B. RF with Others, and Photo of Lesley Frost C. Homes and Farms Where RF Lived D. Photographic Reproductions E. Framed Photographs, Letters, Lithographs, Drawing Box 6 VI. LANKES WOODCUTS VII. PHILATELIC MEMENTOS VIII. MEDALS AND BUSTS IX. MATERIAL RELATED TO RF A. Dedication of the Richards-Frost Room X. CORRESPONDENCE C&NCERNING FROST COLLECTORS A. William E. Stockhausen and others Boxes 6,7 B. Paul C. Richards RICHARDS-FROST ROOM Robert Frost Inventory Gift of Paul C. Richards 1975- Box 1 I. MANUSCRIPTS BY ROBERT FROST A.