Human Relationships in the Poetry of Robert Frost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bookman Anthology of Verse

The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Edited by John Farrar The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Table of Contents The Bookman Anthology Of Verse..........................................................................................................................1 Edited by John Farrar.....................................................................................................................................1 Hilda Conkling...............................................................................................................................................2 Edwin Markham.............................................................................................................................................3 Milton Raison.................................................................................................................................................4 Sara Teasdale.................................................................................................................................................5 Amy Lowell...................................................................................................................................................7 George O'Neil..............................................................................................................................................10 Jeanette Marks..............................................................................................................................................11 John Dos Passos...........................................................................................................................................12 -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

ENG 351 Lecture 33 1 Let's Finish Discussing Gwendolyn Brooks. I

ENG 351 Lecture 33 1 Let’s finish discussing Gwendolyn Brooks. I would like your indulgence to make up for last time. I really was blind. It was — and one of you saved my life, with my visual migraine which sent me into something of a panic. Something else I’ve learned is you should never — you should never read a poem in public that you haven’t read for many years. It can sneak up on you and kick you, and that’s what this poem did. I haven’t looked at The Chicago Defender poem for a long, long, long time. And here I am, half blinded, and then I got emotional at the end of it. So I apologize for that and see if I can get through this with a decent reading. That happened to me one time before with a poem called “April Inventory” by W. D. Snodgrass. And sometimes, you know, poetry has a — has a way of getting to you, whether you want it to or not. But let me — it’s a good poem. It’s only a few minutes long. If you can bear with it, I wanted to get that on in the lesson. This was the poem that I asked Gwendolyn Brooks why she didn’t read it while she was here and she said she no longer liked the ending of it. So I particularly want you to pay attention to the ending of it. She asked me why I liked it and I said because I’m from Little Rock, and then she inquired, “How old were you in 1957?” And when I told her I was eleven, it was okay. -

Robert Frostâ•Žs Theory and Practice of Poetry

/~/ ROBERT FROST’S THEORY AND PRACTICE OF POETRY A THESIS SUN~ITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ~TLANTh UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILII4ENT OF ThE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY EMMA L • YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY 1967 ~ ~ ~53 /J~:.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iii INTRODUCTION . vi Chapter I. Frost’s Theory of Poetry . I. II. Major Themes in Frost’s Poetry 16 III. Frost’s Language and Style 30 CONCLUSION . 49 B IBLIOGR.APHY . 5 1 11 PREFACE Although Robert Frost occupies a unique position in modern poetry, he has not received the careful critical evaluation his work deserves. Anyone who has studied the numerous articles and books about him is quick to note that much has been done in the way of biographical sketches, regional vignettes, and appreciation, but little effort has been made to examine the poetry itself. There are many reasons for this lack of serious consideration. The main cause, however, is to be found in the very nature of his art. The poetry he has written is of a type distinctly different from that of his major contemporaries. At first glance, his work has an unusual simplicity which sets it apart. Frost’s poetry does not conform to any of the conventional devices characteristic of modern poetry. Modern poetry often exhibits obscurities of style and fra~nentary sentences, whereas, Frost’s sentences are clear. In modern poetry the verse forms are irregular with abrupt shifts from subject to subject. Frost’s language is conventional - close to everyday speech. Because he demands less erudition in the reader, his poetry may appear to lack the depth of thought that is found in the best modern verse. -

Robert Frost

Patrick Elisa Wells And dear friend, Roberto Frost A Rose for Patrick.. Robert Frost Born Robert Lee Frost on March 26,1874 in San Francisco, California to William Prescott Frost Jr. Isabelle Moodie. His parents had Scottish and England descent. His father died in 1885, and he and his mother moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts under the patronage of Robert's grandfather. There his mother joined the Swedenborgian church where he was baptised, but he left the church in his adulthood. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892. It was there that he published his first poems, "La Noche Triste," and "The Song of the Wave," in the school's magazine. He then met and fell in love with fellow student Elinor Miriam White. The year of his graduation, he became engaged to Elinor. He attended Dartmouth College instead of Harvard because it was cheaper. He was there just long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. He was so bored by college life that he left at the end of his first semester. Frost tries to convince Elinor to marry him before returning to St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, but fails. After leaving college, he returned home to teach and to work at various jobs including delivering newspapers and factory labor. Truly not enjoying these jobs at all, he felt his true calling as a poet. A year later, he learns that The Independent will publish his poem "My Butterfly: An Elegy" and would pay him $15. He once again tried to convince Elinor to marry him at once. -

John Gould Fletcher - Poems

Classic Poetry Series John Gould Fletcher - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive John Gould Fletcher(3 January 1886 – 10 May 1950) John Gould Fletcher was an Imagist poet, author and authority on modern painting. He was born in Little Rock, Arkansas to a socially prominent family. After attending Phillips Academy, Andover Fletcher went on to Harvard University from 1903 to 1907, when he dropped out shortly after his father's death. <b>Background</b> Fletcher lived in England for a large portion of his life. While in Europe he associated with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/amy-lowell/">Amy Lowell</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/ezra-pound/">Ezra Pound</a>, and other Imagist poets, he was one of the six Imagists who adopted the name and stuck to it until their aims were achieved. Fletcher resumed a liaison with Florence Emily “Daisy” Arbuthnot (née Goold) at her house in Kent. She had been married to Malcolm Arbuthnot and Fletcher's adultery with her was the grounds for the divorce. The couple married on July 5, 1916. Their marriage produced no children, but Arbuthnot’s son and daughter from her previous marriage lived with the couple. On January 18, 1936 he married a noted author of children's books, Charlie May Simon. The two of them built "Johnswood", a residence on the bluffs of the Arkansas River outside Little Rock. They traveled frequently, however, to New York for the intellectual stimulation and to the American Southwest for the climate, after Fletcher began to suffer from arthritis. -

Robert Frosts Poetry: the Duality of the Senex

ROBERT FROSTS POETRY: THE DUALITY OF THE SENEX SONJA VALČIĆ UDK: 820(73).FROST, R. Filozofski fakultet u Zadru Izvorni znanstveni članak Faculty o f Philosophy in Zadar Original scientific paper Primljeno. 1999_10_12 Received The senex archetype in Frost's poetry is used extensively, it serves him to portray three antithetical aspects of human condition, aspects characterized by both positive and negative categories. These categories are not portrayed as static divisions, but as poles dinamically and complexly interrelated. This paper examines three of Frost's works "Mending Wall", "An Old Man's Winter Night" and "Directive" as examples for the study of the paradoxical senex consciousness. While the archetypal senex figures in the "Directive" and "An Old Man's Winter Night" represent primarily the antithetical aspects of the nature of humans, the senex protagonists in the "Mending Wall" reflect the inherent binary oppositions and ambivalence within the contradictory and paradoxical world of humankind. Thus, we can say, that Frost's portrayal of the archetype of the senex acknowledges the symbolic paradigm of the human condition. I. Robert Frost has long been considered the "Wise Old Man" of American twentieth-century poets, not simply because of his public persona, or mask, but because, as I shall explore in this paper, so much of his poetry and the characters in his poetry manifest the temperament, nature, principles and ordering qualities of the senex archetype. Senex is the Latin word for old man (or old woman). Personifications of the archetype appear everywhere in Frost's work as the guide, judge, father, mentor, philosopher, literate farmer, king, ruler (President and Governor), preacher, hermit, outcast, exile and ogre. -

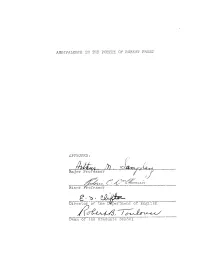

Ambivalence in the Poetry of Robert Frost Approved

AMBIVALENCE IN THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST APPROVED: / /' 4- fell Major Professor •f l> Minor Frofessoi Director of the Department, of English Dean of the Graduate School AMBIVALENCE IN THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By- Patricia F. White, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1967 TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. AMBIVALENCE: A CENTRAL ASPECT OF FROST'S POETRY 14 III. ESCAPE AND RETURN ..... 28 IV. ADVANCE AND RETREAT ..... 39 V. ROMANTICISM AND REALISM 58 VI. FAITH AND SKEPTICISM 77 VII. CONCLUSION 93 BIBLIOGRAPHY 97 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION / One of the most striking features of Frost's poetry / \ noted by critics who have surveyed the body of his work is that quality which has been variously described in such ^ terms as contrariety, polarity, contradiction, or opposition and which is referred to in this study by the all-inclusive x term ambivalence. Critics have responded to this quality in Frost with varying degrees of both sympathy and antipathy, the particular response depending, at least in part, on the temperamental bias that the critic, no matter how carefully he guards his objectivity, brings to his subject. Among those critics who deny to Frost a front rank position among the great poets of the century, especially those critics who eye with suspicion Frost's enormous popularity among the Philistines, it seems to be those qualities related directly or indirectly to his ambivalence that are a chief target of critical comment. -

Nietzsche for Physicists

Nietzsche for physicists Juliano C. S. Neves∗ Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Instituto de Matemática, Estatística e Computação Científica, CEP. 13083-859, Campinas, SP, Brazil Abstract One of the most important philosophers in history, the German Friedrich Nietzsche, is almost ignored by physicists. This author who declared the death of God in the 19th century was a science enthusiast, especially in the second period of his work. With the aid of the physical concept of force, Nietzsche created his concept of will to power. After thinking about energy conservation, the German philosopher had some inspiration for creating his concept of eternal recurrence. In this article, some influences of physics on Nietzsche are pointed out, and the topicality of his epistemological position—the perspectivism—is discussed. Considering the concept of will to power, I propose that the perspectivism leads to an interpretation where physics and science in general are viewed as a game. Keywords: Perspectivism, Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, Physics 1 Introduction: an obscure philosopher? The man who said “God is dead” (GS §108)1 is a popular philosopher well-regarded world- wide. Nietzsche is a strong reference in philosophy, psychology, sociology and the arts. But did Nietzsche have any influence on natural sciences, especially on physics? Among physi- cists and scientists in general, the thinker who created a philosophy that argues against the Platonism is known as an obscure or irrationalist philosopher. However, contrary to common arXiv:1611.08193v3 [physics.hist-ph] 15 May 2018 ideas, although Nietzsche was critical about absolute rationalism, he was not an irrationalist. Nietzsche criticized the hubris of reason (the Socratic rationalism2): the belief that mankind ∗[email protected] 1Nietzsche’s works are indicated by the initials, with the correspondent sections or aphorisms, established by the critical edition of the complete works edited by Colli and Montinari [Nietzsche, 1978]. -

“Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

FROST POETRY ANALYSIS DIRECTIONS: Complete the TP-CASTT analysis chart for your group poem. You only need one paper per group, but you are all responsible for presenting your poem to the class. You each must speak and contribute to the presentation. TP-CASTT –an acronym for title, paraphrase, connotation, attitude, shift, title (again), and theme—is designed to help you remember the concepts you can consider when examining a poem. This is not a lockstep sequential approach, but rather it is a fluid process in which you will move back and forth, among the various concepts. For example, in examining connotations of a line, you may also notice a shift, which in turn may give you an insight into theme. Title (before reading) Although titles are often keys to possible meanings of a poem, students frequently do not contemplate them either before or after reading poetry. As a first step in the analysis of a new poem, look at the title and predict what the poem may be about. Paraphrase Another aspect of a poem often neglected by students is the literal meaning—the “plot.” Frequently, real understanding of a poem must evolve from comprehension of “what’s going on in the poem.” Try to restate a poem in your own words, focusing on one syntactical unit at a time—not necessarily on one line at a time. Another possibility is to write a sentence or two for each stanza of the poem. Connotation Although this term usually refers solely to the emotional overtones of word choice, here it indicates that you should examine any and all poetic devices, focusing on how such devices contribute to the meaning, the effect, or both of a poem. -

Birches & Mending Wall King’S Word Academy BIRCHES When I See Birches Bend to Left and Right Across the Lines of Straighter Darker Trees

Literature Birches & Mending Wall King’s Word Academy BIRCHES When I see birches bend to left and right Across the lines of straighter darker trees. I like to think some boy’s been swinging them. But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay 5 As ice storms do. Often you must have seen them Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning After a rain. They click upon themselves As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel. 10 Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells Shattering and avalanching on the snow crust- Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen. They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load. 15 And they seem not to break: though once they are bowed So low for long, they never right themselves: You may see their trunks arching in the woods Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair 20 Before them over their heads to dry in the sun. But I was going to say when Truth broke in With all her matter of fact about the ice storm, I should prefer to have some boy bend them As he went out and in to fetch the cows- 25 Some boy too far from town to learn baseball. Whose only play was what he found himself. Summer or winter, and could play alone. One by one he subdued his father’s trees By riding them down over and over again 30 Until he took the stiffness out of them And not one but hung limp, not one was left For him to conquer. -

Phonological Features in Robert Frost's “Fire and Ice” and “Nothing Gold Can Stay” Poems

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PHONOLOGICAL FEATURES IN ROBERT FROST’S “FIRE AND ICE” AND “NOTHING GOLD CAN STAY” POEMS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By HADRIAN KUSUMA ASMARA Student Number: 144214071 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PHONOLOGICAL FEATURES IN ROBERT FROST’S “FIRE AND ICE” AND “NOTHING GOLD CAN STAY” POEMS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By HADRIAN KUSUMA ASMARA Student Number: 144214071 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI v PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vi PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Time is never Waiting For us To Do Something vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI This Page is dedicated for CHRISTIAN KUSUMA ASMARA viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to send my deepest gratefulness to Jesus Christ for all blessing during and after the process of writing this thesis. I thank Him because He has accompanied me through my family and my friends who always support me in every situation I have. Secondly, I would like to extend my gratitude to my thesis advisor, Arina Isti’anah, S.Pd., M.Hum., for understanding my diffculties, guiding me patiently, and supporting me in finishing my thesis. She patiently read my writing and gave me suggestions that made this writing a success.