Translating Mimesis of Orality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TANIZE MOCELLIN FERREIRA Narratology and Translation Studies

TANIZE MOCELLIN FERREIRA Narratology and Translation Studies: an analysis of potential tools in narrative translation PORTO ALEGRE 2019 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS MESTRADO EM LITERATURAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA LINHA DE PESQUISA: SOCIEDADE, (INTER)TEXTOS LITERÁRIOS E TRADUÇÃO NAS LITERATURAS ESTRANGEIRAS MODERNAS Narratology and Translation Studies: an analysis of potential tools in narrative translation Tanize Mocellin Ferreira Dissertação de Mestrado submetida ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Elaine Barros Indrusiak PORTO ALEGRE Agosto de 2019 2 CIP - Catalogação na Publicação Ferreira, Tanize Mocellin Narratology and Translation Studies: an analysis of potential tools in narrative translation / Tanize Mocellin Ferreira. -- 2019. 98 f. Orientadora: Elaine Barros Indrusiak. Dissertação (Mestrado) -- Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Letras, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, Porto Alegre, BR-RS, 2019. 1. tradução literária. 2. narratologia. 3. Katherine Mansfield. I. Indrusiak, Elaine Barros, orient. II. Título. Elaborada pelo Sistema de Geração Automática de Ficha Catalográfica da UFRGS com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a). Tanize Mocellin Ferreira Narratology and Translation Studies: an analysis of potential tools in narrative translation Dissertação de Mestrado submetida ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras -

Robert Frostâ•Žs Theory and Practice of Poetry

/~/ ROBERT FROST’S THEORY AND PRACTICE OF POETRY A THESIS SUN~ITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ~TLANTh UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILII4ENT OF ThE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY EMMA L • YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY 1967 ~ ~ ~53 /J~:.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iii INTRODUCTION . vi Chapter I. Frost’s Theory of Poetry . I. II. Major Themes in Frost’s Poetry 16 III. Frost’s Language and Style 30 CONCLUSION . 49 B IBLIOGR.APHY . 5 1 11 PREFACE Although Robert Frost occupies a unique position in modern poetry, he has not received the careful critical evaluation his work deserves. Anyone who has studied the numerous articles and books about him is quick to note that much has been done in the way of biographical sketches, regional vignettes, and appreciation, but little effort has been made to examine the poetry itself. There are many reasons for this lack of serious consideration. The main cause, however, is to be found in the very nature of his art. The poetry he has written is of a type distinctly different from that of his major contemporaries. At first glance, his work has an unusual simplicity which sets it apart. Frost’s poetry does not conform to any of the conventional devices characteristic of modern poetry. Modern poetry often exhibits obscurities of style and fra~nentary sentences, whereas, Frost’s sentences are clear. In modern poetry the verse forms are irregular with abrupt shifts from subject to subject. Frost’s language is conventional - close to everyday speech. Because he demands less erudition in the reader, his poetry may appear to lack the depth of thought that is found in the best modern verse. -

Robert Frost

Patrick Elisa Wells And dear friend, Roberto Frost A Rose for Patrick.. Robert Frost Born Robert Lee Frost on March 26,1874 in San Francisco, California to William Prescott Frost Jr. Isabelle Moodie. His parents had Scottish and England descent. His father died in 1885, and he and his mother moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts under the patronage of Robert's grandfather. There his mother joined the Swedenborgian church where he was baptised, but he left the church in his adulthood. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892. It was there that he published his first poems, "La Noche Triste," and "The Song of the Wave," in the school's magazine. He then met and fell in love with fellow student Elinor Miriam White. The year of his graduation, he became engaged to Elinor. He attended Dartmouth College instead of Harvard because it was cheaper. He was there just long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. He was so bored by college life that he left at the end of his first semester. Frost tries to convince Elinor to marry him before returning to St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, but fails. After leaving college, he returned home to teach and to work at various jobs including delivering newspapers and factory labor. Truly not enjoying these jobs at all, he felt his true calling as a poet. A year later, he learns that The Independent will publish his poem "My Butterfly: An Elegy" and would pay him $15. He once again tried to convince Elinor to marry him at once. -

Selections from Joe Sachs's Introduction to His Translation of Aristotle's Metaphysics (Sachs's Extensive Footnotes Have Been Omitted from This Selection.)

Selections from Joe Sachs's Introduction to His Translation of Aristotle's Metaphysics (Sachs's extensive footnotes have been omitted from this selection.) How and Why this Version Differs from Others We cannot give an accurate summary of Aristotle's conclusions about the way things are unless we have some way to translate his characteristic vocabulary, but if our decision is to follow the prevalent habits of the most authoritative interpreters, those conclusions crumble away into nothing. By way of the usual translations, the central argument of the Metaphysics would be: being qua being is being per se in accordance with the categories, which in turn is primarily substance, but primary substance is form, while form is essence and essence is actuality. You might react to such verbiage in various ways. You might think, I am too ignorant and untrained to understand these things, and need an expert to explain them to me. Or you might think, Aristotle wrote gibberish. But if you have some acquaintance with the classical languages, you might begin to be suspicious that something has gone awry: Aristotle wrote Greek, didn't he? And while this argument doesn't sound much like English, it doesn't sound like Greek either, does it? In fact this argument appears to be written mostly in an odd sort of Latin, dressed up to look like English. Why do we need Latin to translate Greek into English at all? At all the most crucial places, the usual translations of Aristotle abandon English and move toward Latin. They do this because earlier translations did the same. -

HEXIS and GRACE: the FORMATION of SOULS at PORT ROYAL and ELSEWHERE INTRODUCTION N the Middle of the Seventeenth Century The

RICH COCHRANE HEXIS AND GRACE: THE FORMATION OF SOULS AT PORT ROYAL AND ELSEWHERE INTRODUCTION n the middle of the seventeenth century the Cistercian convent known as Port Royal became simultaneously, and connectedly, a centre of pedagogic innovation and religious I controversy. Its “little schools,” which educated (separately) both girls and boys, are now famous largely for the publication of two textbooks, one on logic and another on grammar, which have been seen by some commentators as early documents of the Enlightenment.1 These were associated exclusively with the education of the boys. The girls’ education, however, also produced an important document: the Rule for Children of Jacqueline Pascal,2 who directed the girls’ school at Port Royal des Champs (the old site that lay outside Paris) during the 1650s. This paper gives an interpretation of this text and the educational practice it records and suggests not only that this practice has deep roots in the Christian tradition but also that it continues to exert a powerful, albeit indirect, influence on our thinking about education today. I begin by discussing in some detail the related notions of hexis and divine grace, which in Augustine come together to create a doctrine that had a profound influence on Jansen and his followers. I then proceed to read Pascal’s Rule in the light of this doctrine. I show that the purpose of the regime she supervised was the preparation of the soul to receive grace, making it an early example of a formative pedagogy as opposed to an “informative” one. My aim is to understand the theory embedded in the pedagogic practices Pascal describes rather than to import a theory of practice from elsewhere.3 The extent to which the roots of Pascal’s pedagogy 1 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (London: Routledge, 1989), 46; 67 et passim; 104 et passim; 195. -

Loan and Calque Found in Translation from English to Indonesian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8435 An International Peer-reviewed Journal DOI: 10.7176/JLLL Vol.54, 2019 Loan and Calque Found in Translation from English to Indonesian Marlina Adi Fakhrani Batubara A Postgraduate student of Translation Studies in University of Gunadarma, Depok, Indonesia Abstract The aim of this article is to find out the cause of using loan and calque found in translation from English to Indonesian, find out which strategy is mostly used in translating some of the words and phrases found in translation from English to Indonesian and what form that is usually use loan and calque in the translation. Data of this article is obtained from the English novel namely Murder in the Orient Express by Agatha Christie and its Indonesian translation. This article concluded that out of 100 data, 57 data uses loan and 47 data uses calque. Moreover, it shows that 70 data are in the form of words that uses loan or calque and 30 data are in the form of phrases that uses loan or calque. Keywords: Translation, Strategy, Loan and Calque. DOI : 10.7176/JLLL/54-03 Publication date :March 31 st 2019 1. INTRODUCTION Every country has their own languages in order to express their intentions or to communicate. Language plays a great tool for humans to interact with each other. Goldstein (2008) believed that “We can define language as a system of communication using sounds or symbols that enables us to express our feelings, thoughts, ideas and experiences.” (p. -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

Robert Frosts Poetry: the Duality of the Senex

ROBERT FROSTS POETRY: THE DUALITY OF THE SENEX SONJA VALČIĆ UDK: 820(73).FROST, R. Filozofski fakultet u Zadru Izvorni znanstveni članak Faculty o f Philosophy in Zadar Original scientific paper Primljeno. 1999_10_12 Received The senex archetype in Frost's poetry is used extensively, it serves him to portray three antithetical aspects of human condition, aspects characterized by both positive and negative categories. These categories are not portrayed as static divisions, but as poles dinamically and complexly interrelated. This paper examines three of Frost's works "Mending Wall", "An Old Man's Winter Night" and "Directive" as examples for the study of the paradoxical senex consciousness. While the archetypal senex figures in the "Directive" and "An Old Man's Winter Night" represent primarily the antithetical aspects of the nature of humans, the senex protagonists in the "Mending Wall" reflect the inherent binary oppositions and ambivalence within the contradictory and paradoxical world of humankind. Thus, we can say, that Frost's portrayal of the archetype of the senex acknowledges the symbolic paradigm of the human condition. I. Robert Frost has long been considered the "Wise Old Man" of American twentieth-century poets, not simply because of his public persona, or mask, but because, as I shall explore in this paper, so much of his poetry and the characters in his poetry manifest the temperament, nature, principles and ordering qualities of the senex archetype. Senex is the Latin word for old man (or old woman). Personifications of the archetype appear everywhere in Frost's work as the guide, judge, father, mentor, philosopher, literate farmer, king, ruler (President and Governor), preacher, hermit, outcast, exile and ogre. -

The Stoics and the Practical: a Roman Reply to Aristotle

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2013 The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle Robin Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Robin, "The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle" (2013). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 143. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STOICS AND THE PRACTICAL: A ROMAN REPLY TO ARISTOTLE A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 BY Robin Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL - TABLE OF CONTENTS - Introduction……………………..............................................................................................................p.i Chapter One: Practical Knowledge and its Others Technê and Natural Philosophy…………………………….....……..……………………………….....p. 1 Virtue and technical expertise conflated – subsequently distinguished in Plato – ethical knowledge contrasted with that of nature in -

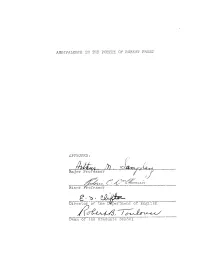

Ambivalence in the Poetry of Robert Frost Approved

AMBIVALENCE IN THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST APPROVED: / /' 4- fell Major Professor •f l> Minor Frofessoi Director of the Department, of English Dean of the Graduate School AMBIVALENCE IN THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By- Patricia F. White, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1967 TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. AMBIVALENCE: A CENTRAL ASPECT OF FROST'S POETRY 14 III. ESCAPE AND RETURN ..... 28 IV. ADVANCE AND RETREAT ..... 39 V. ROMANTICISM AND REALISM 58 VI. FAITH AND SKEPTICISM 77 VII. CONCLUSION 93 BIBLIOGRAPHY 97 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION / One of the most striking features of Frost's poetry / \ noted by critics who have surveyed the body of his work is that quality which has been variously described in such ^ terms as contrariety, polarity, contradiction, or opposition and which is referred to in this study by the all-inclusive x term ambivalence. Critics have responded to this quality in Frost with varying degrees of both sympathy and antipathy, the particular response depending, at least in part, on the temperamental bias that the critic, no matter how carefully he guards his objectivity, brings to his subject. Among those critics who deny to Frost a front rank position among the great poets of the century, especially those critics who eye with suspicion Frost's enormous popularity among the Philistines, it seems to be those qualities related directly or indirectly to his ambivalence that are a chief target of critical comment. -

“Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

FROST POETRY ANALYSIS DIRECTIONS: Complete the TP-CASTT analysis chart for your group poem. You only need one paper per group, but you are all responsible for presenting your poem to the class. You each must speak and contribute to the presentation. TP-CASTT –an acronym for title, paraphrase, connotation, attitude, shift, title (again), and theme—is designed to help you remember the concepts you can consider when examining a poem. This is not a lockstep sequential approach, but rather it is a fluid process in which you will move back and forth, among the various concepts. For example, in examining connotations of a line, you may also notice a shift, which in turn may give you an insight into theme. Title (before reading) Although titles are often keys to possible meanings of a poem, students frequently do not contemplate them either before or after reading poetry. As a first step in the analysis of a new poem, look at the title and predict what the poem may be about. Paraphrase Another aspect of a poem often neglected by students is the literal meaning—the “plot.” Frequently, real understanding of a poem must evolve from comprehension of “what’s going on in the poem.” Try to restate a poem in your own words, focusing on one syntactical unit at a time—not necessarily on one line at a time. Another possibility is to write a sentence or two for each stanza of the poem. Connotation Although this term usually refers solely to the emotional overtones of word choice, here it indicates that you should examine any and all poetic devices, focusing on how such devices contribute to the meaning, the effect, or both of a poem. -

Birches & Mending Wall King’S Word Academy BIRCHES When I See Birches Bend to Left and Right Across the Lines of Straighter Darker Trees

Literature Birches & Mending Wall King’s Word Academy BIRCHES When I see birches bend to left and right Across the lines of straighter darker trees. I like to think some boy’s been swinging them. But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay 5 As ice storms do. Often you must have seen them Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning After a rain. They click upon themselves As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel. 10 Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells Shattering and avalanching on the snow crust- Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen. They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load. 15 And they seem not to break: though once they are bowed So low for long, they never right themselves: You may see their trunks arching in the woods Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair 20 Before them over their heads to dry in the sun. But I was going to say when Truth broke in With all her matter of fact about the ice storm, I should prefer to have some boy bend them As he went out and in to fetch the cows- 25 Some boy too far from town to learn baseball. Whose only play was what he found himself. Summer or winter, and could play alone. One by one he subdued his father’s trees By riding them down over and over again 30 Until he took the stiffness out of them And not one but hung limp, not one was left For him to conquer.