Heritage and Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860S-1950S?

Journal of New Zealand Studies What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese? What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860s-1950s? MILES FAIRBURN University of Canterbury Dominating the relatively substantial literature on the history of the Chinese in New Zealand is the story of their mistreatment by white New Zealanders from the late 1860s through to the 1950s.1 However, the study of discrimination against the Chinese has now reached something of an impasse, one arising from the strong tendency of researchers in the area to advance their favourite explanations for discrimination without arguing why they prefer these to the alternatives. This practice has led to an increase in the variety of explanations and in the weight of data supporting the explanations, but not to their rigorous appraisal. In consequence, while researchers have told us more and more about which causal factors produced discrimination they have little debated or demonstrated the relative importance of these factors. As there is no reason to believe that all the putative factors are of equal importance, knowledge about the causes is not progressing. The object of this paper is to break the impasse by engaging in a systematic comparative evaluation of the different explanations to determine which one might be considered the best. The best explanation is, of course, not perfect by definition. Moreover, in all likelihood an even better explanation will consist of a combination of that best and one or more of the others. But to find the perfect explanation or a combination of explanations we have to start somewhere. -

Libro EVERYTHING COUNTS Final

Everything Counts! Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America 1 Everything Counts! The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or IDRC Canada concerning that legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the elimination of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or IDRC Canada. The publication of this book was made possible through the financial support provided by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to the project: “Asumiendo el reto de la equidad de género en la gestión ambiental en América Latina”. Pubished by: IUCN-ORMA, The World Conservation Union Regional Office for Mesoamerica, in collaboration with: Rights Reserve: © 2004 The World Conservation Union Reproduction of this text is permitted for non-commercial and educational purposes only. All rights are reserved. Reproduction for sale or any other commercial purposes is strictly prohibited, without written permission from the authors. Quotation: 333.721.4 I -92e IUCN. ORMA. Social Thematic Area Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America / Comp. por IUCN-ORMA. Social Thematic Area; Edit. por Linda Berrón Sañudo; Tr. por Ana Baldioceda Castro. – San José, C.R.: World Conservation Union, IUCN, 2004. 203 p.; 28 cm. ISBN 9968-743- 87 - 9 Título en español: ¡Todo Cuenta! El valor de las iniciativas de conservación con enfoque de género en Latinoamérica 1.Medioambiente. -

Executive Summary

The Boston University Astronomy Department Annual Report 2010 Chair: James Jackson Administrator: Laura Wipf 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 5 Faculty and Staff 5 Teaching 6 Undergraduate Programs 6 Observatory and Facilities 8 Graduate Program 9 Colloquium Series 10 Alumni Affairs/Public Outreach 10 Research 11 Funding 12 Future Plans/Departmental Needs 13 APPENDIX A: Faculty, Staff, and Graduate Students 16 APPENDIX B: 2009/2010 Astronomy Graduates 18 APPENDIX C: Seminar Series 19 APPENDIX D: Sponsored Project Funding 21 APPENDIX E: Accounts Income Expenditures 25 APPENDIX F: Publications 27 Cover photo: An ultraviolet image of Saturn taken by Prof. John Clarke and his group using the Hubble Space Telescope. The oval ribbons toward the top and bottom of the image shows the location of auroral activity near Saturn’s poles. This activity is analogous to Earth’s aurora borealis and aurora australis, the so-called “northern” and “southern lights,” and is caused by energetic particles from the sun trapped in Saturn’s magnetic field. 3 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY associates authored or co-authored a total of 204 refereed, scholarly papers in the disciplines’ most The Department of Astronomy teaches science to prestigious journals. hundreds of non-science majors from throughout the university, and runs one of the largest astronomy degree The funding of the Astronomy Department, the Center programs in the country. Research within the for Space Physics, and the Institute for Astrophysical Astronomy Department is thriving, and we retain our Research was changed this past year. In previous years, strong commitment to teaching and service. only the research centers received research funding, but last year the Department received a portion of this The Department graduated a class of twelve research funding based on grant activity by its faculty. -

Voyages & Travel 1515

Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. CONTENTS Africa . 1 Egypt, The Near East & Middle East . 22 Europe, Russia, Turkey . 39 India, Central Asia & The Far East . 64 Australia & The Pacific . 91 Cover illustration; item 48, Walters . Central & South America . 115 MAGGS BROS. LTD. North America . 134 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR Telephone: ++ 44 (0)20 7493 7160 Alaska & The Poles . 153 Email: [email protected] Bank Account: Allied Irish (GB), 10 Berkeley Square London W1J 6AA Sort code: 23-83-97 Account Number: 47777070 IBAN: GB94 AIBK23839747777070 BIC: AIBKGB2L VAT number: GB239381347 Prices marked with an *asterisk are liable for VAT for customers in the UK. Access/Mastercard and Visa: Please quote card number, expiry date, name and invoice number by mail, fax or telephone. EU members: please quote your VAT/TVA number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of the seller until the price has been discharged in full. © Maggs Bros. Ltd. 2021 Design by Radius Graphics Printed by Page Bros., Norfolk AFRICA Remarkable Original Artworks 1 BATEMAN (Charles S.L.) Original drawings and watercolours for the author’s The First Ascent of the Kasai: being some Records of service Under the Lone Star. A bound volume containing 46 watercolours (17 not in vol.), 17 pen and ink drawings (1 not in vol.), 12 pencil sketches (3 not in vol.), 3 etchings, 3 ms. charts and additional material incl. newspaper cuttings, a photographic nega- tive of the author and manuscript fragments (such as those relating to the examination and prosecution of Jao Domingos, who committed fraud when in the service of the Luebo District). -

Key Concepts, Principles and Practices

AGROECOLOGY: KEY CONCEPTS, PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES Main Learning Points from Training Courses on Agroecology in Solo, Indonesia (5-9 June 2013) and Lusaka, Zambia (20-24 April 2015) TWN Third World Network i Agroecology: Key Concepts, Principles and Practices is published by Third World Network 131 Jalan Macalister 10400 Penang Malaysia and Sociedad Científica Latinoamericana de Agroecología (SOCLA) c/o CENSA 1442 A Walnut St # 405 Berkeley, California 94709 USA Copyright © Third World Network and SOCLA 2015 Cover design: Lim Jee Yuan Printed by Jutaprint 2 Solok Sungai Pinang 3 11600 Penang Malaysia ISBN: 978-967-0747-11-8 ii CONTENTS Background and Introduction v 1. The Crisis of Industrial Agriculture 1 2. Concepts and Principles of Agroecology 7 2.1 Principles 7 2.2 Agroecological practices and systems 9 2.3 Agroecology and traditional farmers knowledge 11 2.4 Agroecology and rural social movements 13 3. The Role of Biodiversity in Ecological Agriculture 15 4. Enhancing Plant Biodiversity for Ecological Pest Management in Agroecosystems 21 5. Agroecological Basis for the Conversion to Organic Management 27 5.1 Crop rotations 28 5.2 Enhancing soil health 30 5.3 Crop diversity 32 5.4 Indicators of sustainability 34 6. Agroecology and Food Sovereignty 37 7. Agroecology and the Design of Resilient Farming Systems for a Planet in Crisis 41 Useful Resources 46 iii iv BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION THE current challenges to agriculture posed by food insecurity and climate change are serious. There is a paradox of increased food production and growing hunger in the world. The global food production system is broken as we are destroying the very base of agricul- ture with unsustainable practices. -

Port Hedland 1860 – 2012 a Tale of Three Booms

Institutions, Efficiency and the Organisation of Seaports: A Comparative Analysis By Justin John Pyvis This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University September 2014 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. .................................... Justin John Pyvis Abstract Ports form an essential part of a country's infrastructure by facilitating trade and ultimately helping to reduce the cost of goods for consumers. They are characterised by solidity in physical infrastructure and legislative frameworks – or high levels of “asset specificity” – but also face the dynamics of constantly changing global market conditions requiring flexible responsiveness. Through a New Institutional Economics lens, the ports of Port Hedland (Australia), Prince Rupert (Canada), and Tauranga (New Zealand) are analysed. This dissertation undertakes a cross-country comparative analysis, but also extends the empirical framework into an historical analysis using archival data for each case study from 1860 – 2012. How each port's unique institutional environment – the constraints, or “rules of the game” – affected their development and organisational structure is then investigated. This enables the research to avoid the problem where long periods of economic and political stability in core institutions can become the key explanatory variables. The study demonstrates how the institutional pay-off structure determines what organisational forms come into existence at each port and where, why and how they direct their resources. Sometimes, even immense political will and capital investment will see a port flounder (Prince Rupert); or great resource booms will never be captured (Port Hedland); other times, the port may be the victim of special interest pressure from afar (Tauranga). -

Item Report Template

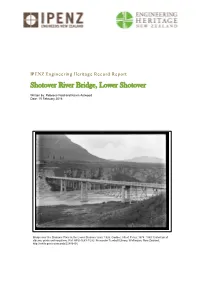

IPENZ Engineering Heritage Record Report Shotover River Bridge, Lower Shotover Written by: Rebecca Ford and Karen Astwood Date: 15 February 2016 Bridge over the Shotover River in the Lower Shotover area, 1926. Godber, Albert Percy, 1875–1949: Collection of albums, prints and negatives. Ref: APG-1683-1/2-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22806436 1 Contents A. General information ....................................................................................................... 3 B. Description .................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................ 5 Historical narrative ................................................................................................................ 5 Social narrative .................................................................................................................. 11 Physical narrative ............................................................................................................... 14 C. Assessment of significance .......................................................................................... 17 D. Supporting information .................................................................................................. 18 List of supporting documents............................................................................................... -

A Comparative Analysis of Nineteenth-Century Californian and New Zealand Newspaper Representations of Chinese Gold Miners

Journal of American-East Asian Relations 18 (2011) 248–273 brill.nl/jaer A Comparative Analysis of Nineteenth-Century Californian and New Zealand Newspaper Representations of Chinese Gold Miners Grant Hannis Massey University Email: [email protected] Abstract During the nineteenth-century gold rush era, Chinese gold miners arrived spontaneously in California and, later, were invited in to work the Otago goldfi elds in New Zealand. Th is article considers how the initial arrival of Chinese in those areas was represented in two major newspapers of the time, the Daily Alta California and the Otago Witness . Both newspapers initially favored Chinese immigration, due to the economic benefi ts that accrued and the generally tolerant outlook of the newspapers’ editors. Th e structure of the papers’ coverage diff ered, however, refl ecting the diff ering historical circumstances of California and Otago. Both papers gave little space to reporting Chinese in their own voices. Th e newspapers editors played the crucial role in shaping each newspaper’s coverage over time. Th e editor of the Witness remained at the helm of his newspaper throughout the survey period and his newspaper consequently did not waver in its support of the Chinese. Th e editor of the Alta , by contrast, died toward the end of the survey period and his newspaper subsequently descended into racist, anti-Chinese rhetoric. Keywords Gold Rush , Chinese gold miners , Daily Alta California , Otago Witness , content analysis , Chinese in California , Chinese in New Zealand A dramatic change in the ethnic mix of the white-dominated western United States occurred in the middle of the nineteenth century, with the sudden infl ux of thousands of Chinese gold miners. -

JOURNAL of AUSTRALASIAN MINING HISTORY Volume 12 October 2014

JOURNAL OF AUSTRALASIAN MINING HISTORY Volume 12 October 2014 Embracing all aspects of mining history, mining archaeology and heritage Published by the Australasian Mining History Association Journal ofAustralasian Mining History ISSN 1448-4471 Published by the Australasian Mining History Association University of Western Australia Editor Mr. Mel Davies, OAM, Hon. Research Fellow, University of Western Australia Sub-editor Mrs. Nicola Williams, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, Monash University Editorial Board Dr. Peter Bell, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, Flinders University Dr. Patrick Berto la, Hon Research Fellow, Curtin University of Technology Prof. Gordon Boyce, University ofNewcastle, NSW Dr. David Branagan, The University ofSydney Prof. Roger Burt, Exeter University, UK Emeritus Prof. David Carment, Charles Darwin University Dr. Graydon Henning, Hon. Research Fellow, University ofNew England Prof. Ken McQueen, University ofCanberra Prof. Jeremy Mouat, University ofAlberta , Canada Prof. Philip Payton, Exeter University, UK Prof. Ian Phimister, Sheffield University, UK Prof. Ian Plimer, University ofAdelaide The Journal of Australasian Mining History accepts papers relating to historical aspects of mining, mining archaeology and heritage in the Australasian region, though consideration will also be given to contributions that will be of general interest to mining historians. Book reviews will also be commissioned. All correspondence should be directed to the Secretary, AMHA, Economics, Business School, MBDP M251, University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Western Australia, or directed via email to: [email protected] The Journal is divided into refereed and non-refereed sections and the papers published in the refereed section will have been subject to a double blind refereeing process. The final decision on publication will lie in the hands of the editor. -

Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS)

Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) PIMS 2050 Terminal Report Project Symbol: UNTS/GLO/002/GEF Project ID: 137561 February 2008 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy TABLE of CONTENTS I. Background of the Project 3 II. Introduction to the GIAHS Concept 3 II. The Project Goal 4 III. Achievements and Outputs of the PDF-B 4 IV. Expected Outcomes/outputs of the PDF-B 5 V. Delivered Outputs 5 VI. International and National Workshops Conducted to support delivery of the Expected Outcomes/Outputs 8 VII. Summary, Constraints, Findings and Recommendations 8 VIII. Administrative and Financial Aspects of the PDF-B 11 A. Detailed disbursement of the resources 11 B. Summary of Components/Activities completed on the Use of PDF-B grant 12 Annex 1. Brief information and agricultural biodiversity characteristics of the five systems selected for the full scale project implementation 14 Annex 2. List of Other GIAHS Systems identified and pre-evaluated systems 19 Annex 3. Summary of the Proposed Components/Expected Outcomes/Outputs of the Full Scale Project 27 Annex 4. Highlights of International Meetings and Workshops Conducted during PDF-B stages 30 2 Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) I. Background of the Project In 2002 a proposal to develop the concept of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) was submitted to the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The UNDP was the implementing agency while FAO served as the executing agency. During the PDF-B stages, preliminary assessment of globally important traditional agricultural systems of the world was prepared together with a baseline on candidate agricultural systems based on desk studies and call of proposals as well as from the outcome of a workshop on concept and identification criteria. -

A1507002 7-01-15 12:24 Pm

FILED 7-01-15 12:24 PM A1507002 Appendix A: Acronyms AAEE Additional Achievable Energy Efficiency AB 327 California Assembly Bill 327 ANSI American National Standards Institute ARB California Air Resources Board AS Ancillary Services ATRA Annual Transmission Reliability Assessment CAISO California Independent System Operator Corporation CDA Customer Data Access CEC California Energy Commission CHP Combined Heat and Power CIP Critical Infrastructure Protection Commission, or CPUC California Public Utilities Commission CSI California Solar Initiative DER(s) Distributed Energy Resource (includes distributed renewable generation resources, energy efficiency, energy storage, electric vehicles, and demand response technologies) DERAC Distributed Energy Resource Avoided Cost DERiM Distributed Energy Resource Interconnection Maps DERMA Distributed Energy Resources Memorandum Account DG Distributed Generation DPP Distribution Planning Process DPRG Distribution Planning Review Group DR Demand Response DRP Distribution Resources Plan DRP Ruling Assigned Commissioner Ruling DRRP Data Request and Release Process DSP Distribution Substation Plan E3 Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. EE Energy Efficiency 3 EIR Electrical Inspection Release EPIC Electric Program Investment Charge ES Energy Storage ESPI Energy Service Provider Interface EV Electric Vehicle FERC Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Final Guidance Guidance for Section 769 – Distribution Resource Planning, attached to the Assigned Commissioner’s Ruling on Guidance for Public Utilities -

Environmentally Sound and Socially Just Alter

AGROECOLOGY: ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND AND SOCIALLY JUST ALTER ... Page 1 of 16 Search Print this chapter Cite this chapter AGROECOLOGY: ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND AND SOCIALLY JUST ALTERNATIVES TO THE INDUSTRIAL FARMING MODEL Miguel A. Altieri University of California, Berkeley Keywords: agroecology, agroforestry systems, traditional agriculture, organic farming, sustainable development, biodiversity Contents 1. Introduction 2. Agroecology and Sustainable Agriculture for Small Farmers in the Developing World 3. Organic Agriculture in the Industrial World 4. Moving Ahead 5. Conclusions Related Chapters Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Two main forms of alternative agriculture which sustain yields without agrochemicals, increasing food security while conserving natural resources, agrobiodiversity, and ecological integrity prevail in the rural landscapes of the world: a more commercial form of organic agriculture and a peasant based more subsistence-oriented traditional agriculture. In this article, the agroecological features of organic agriculture as practiced in North America and Europe, and of traditional agriculture involving millions of small farmers and peasants in the developing world, are described with emphasis on their contribution to food security, conservation/ regeneration of biodiversity, and natural resources and economic viability. 1. Introduction In July 2003, the International Commission on the Future of Food and Agriculture published the Manifesto on the Future of Food. This report warns that corporately controlled, agrochemically based, monocultural, export-oriented agronomic systems are negatively impacting public health, ecosystem intensity, food quality, traditional rural livelihoods, and indigenous and local cultures, while accelerating indebtedness among millions of farmers and their separation from lands that have historically fed communities and families. The growing push toward http://greenplanet.eolss.net.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/EolssLogn/mss/C10/E5-15A..