What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860S-1950S?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Xi Jinping Malaysia Overseas Chinese Affairs Policy

The Study of Xi JinPing Malaysia Overseas Chinese Affairs Policy Toh, Jin-Xuan Xi Jinping, the President of the People’s Republic of China adopted the ideology of “Chinese Dream” as the highest guiding principle in his reign. He also developed the “One Belt One Road” economic strategy as one of his global initiatives. Xi’s aggressive style of ruling means that he has abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s strategy in keeping China in a low profile. His government is getting more active and vocal in the fields of foreign and Overseas Chinese affairs. In this paper, systematic theories are applied to study Xi’s Overseas Chinese policies. With a background research of the history of Overseas Chinese affairs, this paper includes studies on Xi’s “Chinese Dream”, on the assignments of personnel in the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office, and on Xi’s strategies of foreign trade and diplomacy. This paper also explores China’s soft power and its influences upon Malaysian political parties and the Chinese community throughout the implementation of Overseas Chinese policies. This study shows that Xi’s Overseas Chinese policies towards Malaysia are full of challenges. First, China’s active participation in the Overseas Chinese affairs imposes high risks on the fragile relationships among ethnic groups in Malaysia. It might also affect the diplomatic relations between Malaysia and China. Second, China might have to face pressure from the Malaysian government and the Malays when they are working on Overseas Chinese policies towards Malaysia. Third, the Malaysian Chinese community generally upholds “One China policy”, and the business and political leaders of the community have stood up to support the ideology of “Chinese Dream”. -

Localization and the Chinese Overseas: Acculturation, Assimilation, Hybridization, Creolization, and Identification

Cultural and Religious Studies, February 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, 73-87 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2018.02.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Localization and the Chinese Overseas: Acculturation, Assimilation, Hybridization, Creolization, and Identification TAN Chee-Beng Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China Based on materials on the localized Chinese overseas, including the Melaka Babas, who are mostly Malay-speaking Chinese, this article reflects on the use of such terms as acculturation and assimilation, as well as hybridization and creolization, in relation to highly localized Chinese. All these concepts are seen as different ways of describing cultural formation in transcultural context. In particular, the relevance of using creolization to refer to the kind of creative process of cultural formation beyond its original usage in the Caribbean is discussed. This results in the identification of fragmented creolization as in the case of the Caribbean and a rooted creolization as in the case of the Babas. The author shall first discuss the issues of assimilation and integration, followed by hybridization and creolization. This is followed by the discussion on localization of Chinese overseas and identity. The concluding section provides some remarks on the concepts reviewed, and three main categories of acculturated Chinese are identified, namely, Chinese who are linguistically assimilated but still observe major Chinese traditions, Chinese who are so acculturated to the mainstream society that they hardly practice Chinese traditions, and Chinese who are both highly localized and highly mixed “racially”. Keywords: acculturation and assimilation, hybridization, creolization, localization and identity, Baba, Chinese overseas Introduction1 A noticeable feature of Chinese overseas is their local cultural adaptation. -

Voyages & Travel 1515

Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. CONTENTS Africa . 1 Egypt, The Near East & Middle East . 22 Europe, Russia, Turkey . 39 India, Central Asia & The Far East . 64 Australia & The Pacific . 91 Cover illustration; item 48, Walters . Central & South America . 115 MAGGS BROS. LTD. North America . 134 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR Telephone: ++ 44 (0)20 7493 7160 Alaska & The Poles . 153 Email: [email protected] Bank Account: Allied Irish (GB), 10 Berkeley Square London W1J 6AA Sort code: 23-83-97 Account Number: 47777070 IBAN: GB94 AIBK23839747777070 BIC: AIBKGB2L VAT number: GB239381347 Prices marked with an *asterisk are liable for VAT for customers in the UK. Access/Mastercard and Visa: Please quote card number, expiry date, name and invoice number by mail, fax or telephone. EU members: please quote your VAT/TVA number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of the seller until the price has been discharged in full. © Maggs Bros. Ltd. 2021 Design by Radius Graphics Printed by Page Bros., Norfolk AFRICA Remarkable Original Artworks 1 BATEMAN (Charles S.L.) Original drawings and watercolours for the author’s The First Ascent of the Kasai: being some Records of service Under the Lone Star. A bound volume containing 46 watercolours (17 not in vol.), 17 pen and ink drawings (1 not in vol.), 12 pencil sketches (3 not in vol.), 3 etchings, 3 ms. charts and additional material incl. newspaper cuttings, a photographic nega- tive of the author and manuscript fragments (such as those relating to the examination and prosecution of Jao Domingos, who committed fraud when in the service of the Luebo District). -

Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Min Zhou Editor Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Editor Min Zhou University of California Los Angeles, CA USA

Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Min Zhou Editor Contemporary Chinese Diasporas Editor Min Zhou University of California Los Angeles, CA USA ISBN 978-981-10-5594-2 ISBN 978-981-10-5595-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5595-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950830 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Cover image © KTSDESIGN / Getty Images Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

Matrix of Diaspora Institutions

Taxonomy of the Diaspora-Engaging Institutions in 30 Developing Countries More than ever, diasporas — the “scattered seeds” most governments previously ignored and in some cases even maligned — are increasingly seen as agents of development. Aware of this potential, some developing countries have established institutions to more systematically facilitate ties with their diasporas, defined as emigrants and their descendants who have maintained strong sentimental and material links with their countries of origin. The number of countries with diaspora institutions has increased especially in the last ten years, and they range across multiple continents, from Armenia to Somalia to Haiti to India. This table lists the objectives and activities of 45 of these diaspora-engaging institutions in 30 developing countries as well as the year of their creation and links to the institutions' websites, if available. Source: Dovelyn Rannveig Agunias, ed. Closing the Distance: How Governments Strengthen Ties with Their Diasporas. (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2009). Copyright 2010 Migration Policy Institute www.migrationpolicy.org/research/migration_development.php Diaspora Institutions by Type Country Institution Year Key objectives Sample of activities Web site created Ministry-level institutions Armenia Ministry of 2008 Preserve Armenian Planned activities include extending http://www.mindiaspora.am/ Diaspora identity. Discover and tap equal medical aid and educational into the potential of the support to diasporas abroad and diaspora to help empower organizing a series of conferences, the homeland. Facilitate competitions, and festivals in repatriation efforts.1 Armenia. Bangladesh Ministry of 2001 Mainly protect the Provides job placement and http://probashi.gov.bd Expatriates’ overseas employment programs, offers training and Welfare and sector. -

Three Cases in China on Hakka Identity and Self-Perception

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Three cases in China on Hakka identity and self-perception Ricky Heggheim Master’s Thesis in Chinese Studie KIN 4592, 30 Sp Departement of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo 1 Summary Study of Hakka culture has been an academic field for only a century. Compare with many other studies on ethnic groups in China, Hakka study and research is still in her early childhood. This despite Hakka is one of the longest existing groups of people in China. Uncertainty within the ethnicity and origin of Hakka people are among the topics that will be discussed in the following chapters. This thesis intends to give an introduction in the nature and origin of Hakka identity and to figure out whether it can be concluded that Hakka identity is fluid and depending on situations and surroundings. In that case, when do the Hakka people consider themselves as Han Chinese and when do they consider themselves as Hakka? And what are the reasons for this fluidness? Three cases in China serve as the foundation for this text. By exploring three different areas where Hakka people are settled, I hope this text can shed a light on the reasons and nature of changes in identity for Hakka people and their ethnic consciousness as well as the diversities and sameness within Hakka people in various settings and environments Conclusions that are given here indicate that Hakka people in different regions do varies in large degree when it comes to consciousness of their ethnicity and background. -

In China Movement of the Wealthy and Highly Skilled

EMIGRATION TRENDS AND POLICIES IN CHINA MOVEMENT OF THE WEALTHY AND HIGHLY SKILLED By Biao Xiang TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION EMIGRATION TRENDS AND POLICIES IN CHINA Movement of the Wealthy and Highly Skilled Biao Xiang February 2016 Acknowledgments This report benefited greatly from the detailed, constructive comments and editorial help from Kate Hooper and Natalia Banulescu-Bogdan at the Migration Policy Institute. This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its twelfth plenary meeting, held in Lisbon. The meeting’s theme was “Rethinking Emigration: A Lost Generation or a New Era of Mobility?” and this report was among those that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2016 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: Liz Heimann, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. -

AFRICA in CHINA's FOREIGN POLICY

AFRICA in CHINA’S FOREIGN POLICY YUN SUN April 2014 Yun Sun is a fellow at the East Asia Program of the Henry L. Stimson Center. NOTE: This paper was produced during the author’s visiting fellowship with the John L. Thornton China Center and the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings. ABOUT THE JOHN L. THORNTON CHINA CENTER: The John L. Thornton China Center provides cutting-edge research, analysis, dialogue and publications that focus on China’s emergence and the implications of this for the United States, China’s neighbors and the rest of the world. Scholars at the China Center address a wide range of critical issues related to China’s modernization, including China’s foreign, economic and trade policies and its domestic challenges. In 2006 the Brookings Institution also launched the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, a partnership between Brookings and China’s Tsinghua University in Beijing that seeks to produce high quality and high impact policy research in areas of fundamental importance for China’s development and for U.S.-China relations. ABOUT THE AFRICA GROWTH INITIATIVE: The Africa Growth Initiative brings together African scholars to provide policymakers with high-quality research, expertise and innovative solutions that promote Africa’s economic development. The initiative also collaborates with research partners in the region to raise the African voice in global policy debates on Africa. Its mission is to deliver research from an African perspective that informs sound policy, creating sustained economic growth and development for the people of Africa. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: I would like to express my gratitude to the many people who saw me through this paper; to all those who generously provided their insights, advice and comments throughout the research and writing process; and to those who assisted me in the research trips and in the editing, proofreading and design of this paper. -

Port Hedland 1860 – 2012 a Tale of Three Booms

Institutions, Efficiency and the Organisation of Seaports: A Comparative Analysis By Justin John Pyvis This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University September 2014 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. .................................... Justin John Pyvis Abstract Ports form an essential part of a country's infrastructure by facilitating trade and ultimately helping to reduce the cost of goods for consumers. They are characterised by solidity in physical infrastructure and legislative frameworks – or high levels of “asset specificity” – but also face the dynamics of constantly changing global market conditions requiring flexible responsiveness. Through a New Institutional Economics lens, the ports of Port Hedland (Australia), Prince Rupert (Canada), and Tauranga (New Zealand) are analysed. This dissertation undertakes a cross-country comparative analysis, but also extends the empirical framework into an historical analysis using archival data for each case study from 1860 – 2012. How each port's unique institutional environment – the constraints, or “rules of the game” – affected their development and organisational structure is then investigated. This enables the research to avoid the problem where long periods of economic and political stability in core institutions can become the key explanatory variables. The study demonstrates how the institutional pay-off structure determines what organisational forms come into existence at each port and where, why and how they direct their resources. Sometimes, even immense political will and capital investment will see a port flounder (Prince Rupert); or great resource booms will never be captured (Port Hedland); other times, the port may be the victim of special interest pressure from afar (Tauranga). -

Item Report Template

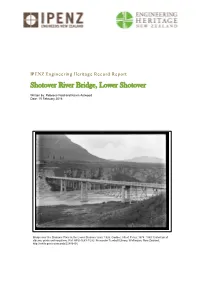

IPENZ Engineering Heritage Record Report Shotover River Bridge, Lower Shotover Written by: Rebecca Ford and Karen Astwood Date: 15 February 2016 Bridge over the Shotover River in the Lower Shotover area, 1926. Godber, Albert Percy, 1875–1949: Collection of albums, prints and negatives. Ref: APG-1683-1/2-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22806436 1 Contents A. General information ....................................................................................................... 3 B. Description .................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................ 5 Historical narrative ................................................................................................................ 5 Social narrative .................................................................................................................. 11 Physical narrative ............................................................................................................... 14 C. Assessment of significance .......................................................................................... 17 D. Supporting information .................................................................................................. 18 List of supporting documents............................................................................................... -

The Chinese Communist Party and the Diaspora Beijing’S Extraterritorial Authoritarian Rule

The Chinese Communist Party and the Diaspora Beijing’s extraterritorial authoritarian rule Oscar Almén FOI-R--4933--SE March 2020 Oscar Almén The Chinese Communist Party and the Diaspora Beijing’s extraterritorial authoritarian rule FOI-R--4933--SE Title The Chinese Communist Party and the Diaspora– Beijing’s extraterritorial authoritarian rule Titel Kinas kommunistparti och diasporan: Pekings extraterritoriella styre Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4933--SE Månad/Month March Utgivningsår/Year 2020 Antal sidor/Pages 65 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet Forskningsområde Säkerhetspolitik FoT-område Projektnr/Project no A 112003 Godkänd av/Approved by Lars Höstbeck Ansvarig avdelning Försvarsanalys Cover: Vancouver, British Columbia / Canada - August 18 2019: Hong Kong Protest and Counter-Protest in Vancouver. (Photo by Eric Kukulowicz, Shutterstock) Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk, vilket bl.a. innebär att citering är tillåten i enlighet med vad som anges i 22 § i nämnd lag. För att använda verket på ett sätt som inte medges direkt av svensk lag krävs särskild överenskommelse. This work is protected by the Swedish Act on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works (1960:729). Citation is permitted in accordance with article 22 in said act. Any form of use that goes beyond what is permitted by Swedish copyright law, requires the written permission of FOI. 2 (65) FOI-R--4933--SE Sammanfattning Denna rapport undersöker det kinesiska kommunistpartiets politik för den kine- siska diasporan samt säkerhetskonsekvenser för diasporan och för de stater där de är bosatta. Eftersom Kina inte accepterar dubbelt medborgarskap är en stor andel av den kinesiska diasporan inte kinesiska medborgare. -

A Comparative Analysis of Nineteenth-Century Californian and New Zealand Newspaper Representations of Chinese Gold Miners

Journal of American-East Asian Relations 18 (2011) 248–273 brill.nl/jaer A Comparative Analysis of Nineteenth-Century Californian and New Zealand Newspaper Representations of Chinese Gold Miners Grant Hannis Massey University Email: [email protected] Abstract During the nineteenth-century gold rush era, Chinese gold miners arrived spontaneously in California and, later, were invited in to work the Otago goldfi elds in New Zealand. Th is article considers how the initial arrival of Chinese in those areas was represented in two major newspapers of the time, the Daily Alta California and the Otago Witness . Both newspapers initially favored Chinese immigration, due to the economic benefi ts that accrued and the generally tolerant outlook of the newspapers’ editors. Th e structure of the papers’ coverage diff ered, however, refl ecting the diff ering historical circumstances of California and Otago. Both papers gave little space to reporting Chinese in their own voices. Th e newspapers editors played the crucial role in shaping each newspaper’s coverage over time. Th e editor of the Witness remained at the helm of his newspaper throughout the survey period and his newspaper consequently did not waver in its support of the Chinese. Th e editor of the Alta , by contrast, died toward the end of the survey period and his newspaper subsequently descended into racist, anti-Chinese rhetoric. Keywords Gold Rush , Chinese gold miners , Daily Alta California , Otago Witness , content analysis , Chinese in California , Chinese in New Zealand A dramatic change in the ethnic mix of the white-dominated western United States occurred in the middle of the nineteenth century, with the sudden infl ux of thousands of Chinese gold miners.