Port Hedland 1860 – 2012 a Tale of Three Booms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY

Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY Published by the Western Australian Planning Commission Final September 2003 Disclaimer This document has been published by the Western Australian Planning Commission. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith and on the basis that the Government, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken (as the case may be) in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. Professional advice should be obtained before applying the information contained in this document to particular circumstances. © State of Western Australia Published by the Western Australian Planning Commission Albert Facey House 469 Wellington Street Perth, Western Australia 6000 Published September 2003 ISBN 0 7309 9330 2 Internet: http://www.wapc.wa.gov.au e-mail: [email protected] Phone: (08) 9264 7777 Fax: (08) 9264 7566 TTY: (08) 9264 7535 Infoline: 1800 626 477 Copies of this document are available in alternative formats on application to the Disability Services Co-ordinator. Western Australian Planning Commission owns all photography in this document unless otherwise stated. Port Hedland AREA PLANNING STUDY Foreword Port Hedland is one of the Pilbara’s most historic and colourful towns. The townsite as we know it was established by European settlers in 1896 as a service centre for the pastoral, goldmining and pearling industries, although the area has been home to Aboriginal people for many thousands of years. In the 1960s Port Hedland experienced a major growth period, as a direct result of the emerging iron ore industry. -

What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860S-1950S?

Journal of New Zealand Studies What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese? What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860s-1950s? MILES FAIRBURN University of Canterbury Dominating the relatively substantial literature on the history of the Chinese in New Zealand is the story of their mistreatment by white New Zealanders from the late 1860s through to the 1950s.1 However, the study of discrimination against the Chinese has now reached something of an impasse, one arising from the strong tendency of researchers in the area to advance their favourite explanations for discrimination without arguing why they prefer these to the alternatives. This practice has led to an increase in the variety of explanations and in the weight of data supporting the explanations, but not to their rigorous appraisal. In consequence, while researchers have told us more and more about which causal factors produced discrimination they have little debated or demonstrated the relative importance of these factors. As there is no reason to believe that all the putative factors are of equal importance, knowledge about the causes is not progressing. The object of this paper is to break the impasse by engaging in a systematic comparative evaluation of the different explanations to determine which one might be considered the best. The best explanation is, of course, not perfect by definition. Moreover, in all likelihood an even better explanation will consist of a combination of that best and one or more of the others. But to find the perfect explanation or a combination of explanations we have to start somewhere. -

ACIL Allen – an Economic Study of Port Hedland Port

REPORT TO REPORT PREPARED FOR THE PORT HEDLAND INDUSTRIES COUNCIL AN ECONOMIC STUDY OF PORT HEDLAND PORT ACIL ALLEN CONSULTING PTY LTD ABN 68 102 652 148 LEVEL FIFTEEN 127 CREEK STREET BRISBANE QLD 4000 AUSTRALIA T+61 7 3009 8700 F+61 7 3009 8799 LEVEL ONE 15 LONDON CIRCUIT CANBERRA ACT 2600 AUSTRALIA T+61 2 6103 8200 F+61 2 6103 8233 LEVEL NINE 60 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 AUSTRALIA T+61 3 8650 6000 F+61 3 9654 6363 LEVEL ONE 50 PITT STREET SYDNEY NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA T+61 2 8272 5100 F+61 2 9247 2455 LEVEL TWELVE, BGC CENTRE 28 THE ESPLANADE PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6000 AUSTRALIA T+61 8 9449 9600 F+61 8 9322 3955 161 WAKEFIELD STREET ADELAIDE SA 5000 AUSTRALIA T +61 8 8122 4965 ACILALLEN.COM.AU REPORT AUTHORS JOHN NICOLAOU, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RYAN BUCKLAND, SENIOR CONSULTANT JAMES HAMMOND, CONSULTANT E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] D: (08) 9449 9616 D: (08) 9449 9621 D: (08) 9449 9415 JOHN NICOLAOU RYAN BUCKLAND JAMES HAMMOND @JANICOLAOU @BUCKLANDACIL @JAMESWHAMMOND1 RELIANCE AND DISCLAIMER THE PROFESSIONAL ANALYSIS AND ADVICE IN THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PREPARED BY ACIL ALLEN CONSULTING FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE PARTY OR PARTIES TO WHOM IT IS ADDRESSED (THE ADDRESSEE) AND FOR THE PURPOSES SPECIFIED IN IT. THIS REPORT IS SUPPLIED IN GOOD FAITH AND REFLECTS THE KNOWLEDGE, EXPERTISE AND EXPERIENCE OF THE CONSULTANTS INVOLVED. THE REPORT MUST NOT BE PUBLISHED, QUOTED OR DISSEMINATED TO ANY OTHER PARTY WITHOUT ACIL ALLEN CONSULTING’S PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT. -

Attachment 13

Appendix 13 Executive Summary ‘The modern world is built on steel which has become essential to economic growth. In developing and developed nations alike, steel is an indispensable part of life … The future growth in demand for steel will be driven mainly by the needs of the developing world.’1 Note: 87% of all world metals consumed are iron and steel. Australia is rich in natural resources. Among the key resources in abundance are iron ore and thermal and coking coal; the key feedstock for steel. Queensland has an abundance of coal, while Western Australia has an abundance of iron ore. Australia has a small population with limited steel production, so these resources are shipped internationally to be used as inputs to steel production. Strong growth in raw steel production and consumption, driven by the rapid industrialisation of China and India in particular, is expected to continue. This will necessitate substantial investment in new global steelmaking capacity. Australia plays a significant leading role in the export steelmaking supply-chain as it has an estimated 40% of the world’s high grade seaborne iron ore and 65% of the world’s seaborne coking coal. Project Iron Boomerang was developed by East West Line Parks Pty Ltd (“EWLP”) to explore the economic feasibility of establishing first-stage steel mill semi-finished steel production in Australia, close to the major raw materials inputs. This Pre-Feasibility Study provides strong evidence that the construction of first-stage smelter precincts offers many cost effective consolidation and efficiency savings, and that a dedicated railroad with all supporting infrastructure is feasible and economically favourable for steelmakers. -

Mines Ministry of Western Australia

Mines Ministry of Western Australia A Mines Ministry was first established in the Forrest Government the first Government after responsible government was obtained in 1890. Since then there have been 39 Ministers for Mines in 34 Governments. Henry Gregory was Minister for Mines in 6 different Governments. Arthur Frederick Griffith was the longest continuous serving Minister for Mines in the Brand Government serving from 1959 - 1971 a period of 12 years. Ministry Name Ministry Title Assumption Retirement of Office Date Of Office Date Forrest (Forrest) Hon. Edward Horne Minister for Mines & Education 19 Dec 1894 12 May 1897 1890 - 1901 Wittenoom, MLC Minister for Mines 12 May 1897 28 April 1898 Hon. Henry Bruce Lefroy, Minister for Mines 28 April 1898 15 Feb 1901 MLA Throssell (Forrest) Hon. Henry Bruce Lefroy, Minister for Mines 15 Feb 1901 27May 1901 1901 MLA Leake (Opp) Hon. Henry Gregory, MLA Minister for Mines 27May 1901 21 Nov 1901 1901 Morgans (Min) Hon. Frank Wilson, MLA Minister for Mines 21 Nov 1901 23 Dec 1901 1901 Leake (Opp) Hon. Henry Gregory, MLA Minister for Mines 23 Dec 1901 1 July 1902 1901 - 1902 James (Lib) Hon. Henry Gregory, MLA Minister for Mines 1 July 1902 10 Aug 1904 1902 - 1904 Daglish (ALP) Hon. Robert Hastie, MLA Minister for Mines 10 Aug 1904 7 June 1905 1904 - 1905 Hon. William Dartnell Minister for Mines & Railways 7 June 1905 25 Aug 1905 Johnson, MLA Rason (Lib) Hon. Henry Gregory, MLA Minister for Mines & Railways 25 Aug 1905 7 May 1906 1905 - 1906 Moore (Min) Hon. Henry Gregory, MLA Minister for Mines & Railways 7 May 1906 16 Sept 1910 1906 - 1910 Wilson (Lib) Hon. -

The Political Career of Senator Paddy Lynch (1867-1944)

With an Olive Branch and a Shillelagh: the Political Career of Senator Paddy Lynch (1867-1944) by Danny Cusack M.A. Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University December 2002 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ……..…………………………… Danny Cusack ABSTRACT As a loyal Empire man and ardent conscriptionist, Irish-born Senator Paddy Lynch swam against the prevailing Irish Catholic Labor political current. He was one of those MP’s who followed Prime Minister W.M. Hughes out of the Federal Labor caucus in November 1916, serving out the rest of his political career in the Nationalist ranks. On the face of things, he represents something of a contradiction. A close examination of Lynch’s youth in Ireland, his early years in Australia and his subsequent parliamentary career helps us to resolve this apparent paradox. It also enables us to build up a picture of Lynch the man and to explain his political odyssey. He emerges as representative of that early generation of conservative Laborites (notably J.C. Watson, W.G. Spence and George Pearce) who, once they had achieved their immediate goals of reform, saw their subsequent role as defending the prevailing social order. Like many of these men, Lynch’s commitment to the labour movement’s principles of solidarity and collective endeavour co-existed with a desire for material self-advancement. More fundamentally, when Lynch accumulated property and was eventually able to take up the occupation which he had known in Ireland – farming – his evolving class interest inevitably occasioned a change in political outlook. -

Voyages & Travel 1515

Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. Voyages & Travel CATALOGUE 1515 MAGGS BROS. LTD. CONTENTS Africa . 1 Egypt, The Near East & Middle East . 22 Europe, Russia, Turkey . 39 India, Central Asia & The Far East . 64 Australia & The Pacific . 91 Cover illustration; item 48, Walters . Central & South America . 115 MAGGS BROS. LTD. North America . 134 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR Telephone: ++ 44 (0)20 7493 7160 Alaska & The Poles . 153 Email: [email protected] Bank Account: Allied Irish (GB), 10 Berkeley Square London W1J 6AA Sort code: 23-83-97 Account Number: 47777070 IBAN: GB94 AIBK23839747777070 BIC: AIBKGB2L VAT number: GB239381347 Prices marked with an *asterisk are liable for VAT for customers in the UK. Access/Mastercard and Visa: Please quote card number, expiry date, name and invoice number by mail, fax or telephone. EU members: please quote your VAT/TVA number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of the seller until the price has been discharged in full. © Maggs Bros. Ltd. 2021 Design by Radius Graphics Printed by Page Bros., Norfolk AFRICA Remarkable Original Artworks 1 BATEMAN (Charles S.L.) Original drawings and watercolours for the author’s The First Ascent of the Kasai: being some Records of service Under the Lone Star. A bound volume containing 46 watercolours (17 not in vol.), 17 pen and ink drawings (1 not in vol.), 12 pencil sketches (3 not in vol.), 3 etchings, 3 ms. charts and additional material incl. newspaper cuttings, a photographic nega- tive of the author and manuscript fragments (such as those relating to the examination and prosecution of Jao Domingos, who committed fraud when in the service of the Luebo District). -

Premiers of Western Australia?

www.elections.wa.gov.au Information sheet State government Premiers of Western Australia? Rt. Hon. Sir John Forrest (afterwards Lord) PC, GCMG 20 Dec 1890 – 14 Feb 1901 Hon. George Throssel CMG 14 Feb 1901 – 27 May 1901 Hon. George Leake KC, CMG 27 May 1901 – 21 Nov 1901 Hon Alfred E Morgans 21 Nov 1901 – 23 Dec 1901 Hon. George Leake KC, CMG 23 Dec 1901 – 24 June 1902 Hon. Walter H James KC, KCMG 1 July 1902 – 10 Aug 1904 Hon. Henry Daglish 10 Aug 1904 – 25 Aug 1905 Hon. Sir Cornthwaite H Rason 25 Aug 1905 – 1 May 1906 Hon. Sir Newton J Moore KCMG 7 May 1906 – 16 Sept 1910 Hon. Frank Wilson CMG 16 Sept 1910 – 7 Oct 1911 Hon. John Scaddan CMG 7 Oct 1911 – 27 July 1916 Hon. Frank Wilson CMG 27 July 1916 – 28 June 1917 Hon. Sir Henry B. Lefroy KCMG 28 June 1917 – 17 Apr 1919 Hon. Sir Hal P Colebatch CMG 17 Apr 1919 – 17 May 1919 Hon. Sir James Mitchell GCMG 17 May 1919 – 16 Apr 1924 Hon. Phillip Collier 17 Apr 1924 – 23 Apr 1930 Hon. Sir James Mitchell GCMG 24 Apr 1930 – 24 Apr 1933 Hon. Phillip Collier 24 Apr1933 – 19 Aug 1936 Hon. John Collings Wilcock 20 Aug 1936 – 31 July 1945 Hon. Frank JS Wise AO 31 July 1945 – 1 Apr 1947 Hon. Sir Ross McLarty KBE, MM 1 Apr 1947 – 23 Feb 1953 Hon. Albert RG Hawke 23 Feb 1953 – 2 Apr 1959 Hon. Sir David Brand KCMG 2 Apr 1959 – 3 Mar 1971 Hon. -

Ports Handbook Western Australia 2016 CONTENTS

Department of Transport Ports Handbook Western Australia 2016 CONTENTS FOREWORD FROM THE MINISTER 3 INTRODUCTION 4 Western Australian port authorities 2015/16 trade volumes 5 Western Australian port authorities 2015/16 marine boundaries and 6 State resources FREMANTLE PORT AUTHORITY 8 Port of Fremantle 8 KIMBERLEY PORTS AUTHORITY 12 Port of Broome 12 MID WEST PORTS AUTHORITY 15 Port of Geraldton 15 PILBARA PORTS AUTHORITY 18 Port of Dampier 19 Port of Port Hedland 21 Port of Ashburton 23 SOUTHERN PORTS AUTHORITY 24 Port of Albany 26 Port of Bunbury 27 Port of Esperance 28 OTHER PORTS 30 Port of Wyndham 32 CONTACTS 34 The Ports Handbook is updated annually, and is available on the Department of Transport website: www.transport.wa.gov.au Cover: Port of Port Hedland Harbour Port of Esperance 22 FOREWORD FROM THE MINISTER Western Australia’s ports are crucial to the The State Government continues to pursue State’s connection with global markets. initiatives to support Western Australia’s ports, This connection provides our State with including the implementation of the WA Ports limitless trade opportunities, and is built on Governance Review, which is progressing well. the State’s reputation as a safe and reliable The benefits from the first tranche of legislative trading partner. reforms are being realised, with new arrangements As one of the most isolated places in the world, that were introduced in 2014 having strengthened Western Australia relies heavily on shipping port governance, expanding port authority for imports and exports. Shipping remains the planning perspectives across their regions and most cost effective mode of transport, and is strengthening the involvement of the State’s ports especially important for our bulk exports to remain in the planning of future transport corridors. -

Street Name Origins in the Town of Bassendean

Street Name Origins in the Town Of Bassendean. P622- Railway Avenue looking towards Lord Street, 2 June 1923 Image in the Local Studies Collection, Bassendean Memorial Library. Disclaimer All effort has been made to ensure the information is accurate at the time of publication, but in many cases, there are no records uncovered as to why a particular road or locality was given its name. In some instances a reasonably likely explanation can be determined, particularly where the name commemorates a known local identity or family. The Local Studies Librarian would be very grateful for any further information about these road names so please be in contact if details should be added or amended. Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Local street names ................................................................................................................................. 7 Alice Street ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Anstey Road ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Anzac Terrace ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Ashfield Parade ................................................................................................................................. -

106/2020 Klimress – Impacts of Climate Change on Mining, Related Environmental Risks and Raw Material Supply

TEXTE 106 /2020 KlimRess – Impacts of climate change on mining, related environmental risks and raw material supply Case studies on bauxite, coking coal and iron ore mining in Australia TEXTE 106/2020 Environmental Research of the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety Project No. (FKZ) 3716 48 324 0 Report No. FB000279/ANH,2,ENG KlimRess – Impacts of climate change on mining, related environmental risks and raw material supply Case studies on bauxite, coking coal and iron ore mining in Australia by Lukas Rüttinger, Christine Scholl, Pia van Ackern adelphi research gGmbh, Berlin and Glen Corder, Artem Golev, Thomas Baumgartl The University of Queensland, Sustainable Minerals Institute, Australia On behalf of the German Environment Agency Imprint Publisher: Umweltbundesamt Wörlitzer Platz 1 06844 Dessau-Roßlau Tel: +49 340-2103-0 Fax: +49 340-2103-2285 [email protected] Internet: www.umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt Study performed by: adelphi research gGmbh Alt-Moabit 91, 10559 Berlin Study completed in: August 2017 Edited by: Section III 2.2 Resource Conservation, Material Cycles, Minerals and Metals Industry Jan Kosmol Publication as pdf: http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen ISSN 1862-4804 Dessau-Roßlau, June 2020 The responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the author(s). UBA Texte header: Please enter name of the project/report (abbreviated, if necessary) Abstract The following case study is one of five country case studies carried out as part of the project ‘Impacts of climate change on the environmental criticality of Germany’s raw material demand‘ (KlimRess), commissioned by the German Federal Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt, UBA). -

Item Report Template

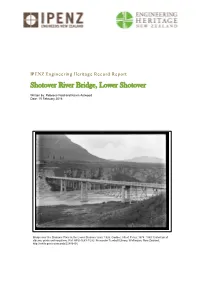

IPENZ Engineering Heritage Record Report Shotover River Bridge, Lower Shotover Written by: Rebecca Ford and Karen Astwood Date: 15 February 2016 Bridge over the Shotover River in the Lower Shotover area, 1926. Godber, Albert Percy, 1875–1949: Collection of albums, prints and negatives. Ref: APG-1683-1/2-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22806436 1 Contents A. General information ....................................................................................................... 3 B. Description .................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................ 5 Historical narrative ................................................................................................................ 5 Social narrative .................................................................................................................. 11 Physical narrative ............................................................................................................... 14 C. Assessment of significance .......................................................................................... 17 D. Supporting information .................................................................................................. 18 List of supporting documents...............................................................................................