Transition Process: Organising Communities Toward Agroecological Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libro EVERYTHING COUNTS Final

Everything Counts! Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America 1 Everything Counts! The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or IDRC Canada concerning that legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the elimination of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or IDRC Canada. The publication of this book was made possible through the financial support provided by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to the project: “Asumiendo el reto de la equidad de género en la gestión ambiental en América Latina”. Pubished by: IUCN-ORMA, The World Conservation Union Regional Office for Mesoamerica, in collaboration with: Rights Reserve: © 2004 The World Conservation Union Reproduction of this text is permitted for non-commercial and educational purposes only. All rights are reserved. Reproduction for sale or any other commercial purposes is strictly prohibited, without written permission from the authors. Quotation: 333.721.4 I -92e IUCN. ORMA. Social Thematic Area Everything Counts! Valuing environmental initiatives with a gender equity perspective in Latin America / Comp. por IUCN-ORMA. Social Thematic Area; Edit. por Linda Berrón Sañudo; Tr. por Ana Baldioceda Castro. – San José, C.R.: World Conservation Union, IUCN, 2004. 203 p.; 28 cm. ISBN 9968-743- 87 - 9 Título en español: ¡Todo Cuenta! El valor de las iniciativas de conservación con enfoque de género en Latinoamérica 1.Medioambiente. -

Key Concepts, Principles and Practices

AGROECOLOGY: KEY CONCEPTS, PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES Main Learning Points from Training Courses on Agroecology in Solo, Indonesia (5-9 June 2013) and Lusaka, Zambia (20-24 April 2015) TWN Third World Network i Agroecology: Key Concepts, Principles and Practices is published by Third World Network 131 Jalan Macalister 10400 Penang Malaysia and Sociedad Científica Latinoamericana de Agroecología (SOCLA) c/o CENSA 1442 A Walnut St # 405 Berkeley, California 94709 USA Copyright © Third World Network and SOCLA 2015 Cover design: Lim Jee Yuan Printed by Jutaprint 2 Solok Sungai Pinang 3 11600 Penang Malaysia ISBN: 978-967-0747-11-8 ii CONTENTS Background and Introduction v 1. The Crisis of Industrial Agriculture 1 2. Concepts and Principles of Agroecology 7 2.1 Principles 7 2.2 Agroecological practices and systems 9 2.3 Agroecology and traditional farmers knowledge 11 2.4 Agroecology and rural social movements 13 3. The Role of Biodiversity in Ecological Agriculture 15 4. Enhancing Plant Biodiversity for Ecological Pest Management in Agroecosystems 21 5. Agroecological Basis for the Conversion to Organic Management 27 5.1 Crop rotations 28 5.2 Enhancing soil health 30 5.3 Crop diversity 32 5.4 Indicators of sustainability 34 6. Agroecology and Food Sovereignty 37 7. Agroecology and the Design of Resilient Farming Systems for a Planet in Crisis 41 Useful Resources 46 iii iv BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION THE current challenges to agriculture posed by food insecurity and climate change are serious. There is a paradox of increased food production and growing hunger in the world. The global food production system is broken as we are destroying the very base of agricul- ture with unsustainable practices. -

Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS)

Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) PIMS 2050 Terminal Report Project Symbol: UNTS/GLO/002/GEF Project ID: 137561 February 2008 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy TABLE of CONTENTS I. Background of the Project 3 II. Introduction to the GIAHS Concept 3 II. The Project Goal 4 III. Achievements and Outputs of the PDF-B 4 IV. Expected Outcomes/outputs of the PDF-B 5 V. Delivered Outputs 5 VI. International and National Workshops Conducted to support delivery of the Expected Outcomes/Outputs 8 VII. Summary, Constraints, Findings and Recommendations 8 VIII. Administrative and Financial Aspects of the PDF-B 11 A. Detailed disbursement of the resources 11 B. Summary of Components/Activities completed on the Use of PDF-B grant 12 Annex 1. Brief information and agricultural biodiversity characteristics of the five systems selected for the full scale project implementation 14 Annex 2. List of Other GIAHS Systems identified and pre-evaluated systems 19 Annex 3. Summary of the Proposed Components/Expected Outcomes/Outputs of the Full Scale Project 27 Annex 4. Highlights of International Meetings and Workshops Conducted during PDF-B stages 30 2 Conservation and Adaptive Management of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) I. Background of the Project In 2002 a proposal to develop the concept of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) was submitted to the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The UNDP was the implementing agency while FAO served as the executing agency. During the PDF-B stages, preliminary assessment of globally important traditional agricultural systems of the world was prepared together with a baseline on candidate agricultural systems based on desk studies and call of proposals as well as from the outcome of a workshop on concept and identification criteria. -

Environmentally Sound and Socially Just Alter

AGROECOLOGY: ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND AND SOCIALLY JUST ALTER ... Page 1 of 16 Search Print this chapter Cite this chapter AGROECOLOGY: ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND AND SOCIALLY JUST ALTERNATIVES TO THE INDUSTRIAL FARMING MODEL Miguel A. Altieri University of California, Berkeley Keywords: agroecology, agroforestry systems, traditional agriculture, organic farming, sustainable development, biodiversity Contents 1. Introduction 2. Agroecology and Sustainable Agriculture for Small Farmers in the Developing World 3. Organic Agriculture in the Industrial World 4. Moving Ahead 5. Conclusions Related Chapters Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Two main forms of alternative agriculture which sustain yields without agrochemicals, increasing food security while conserving natural resources, agrobiodiversity, and ecological integrity prevail in the rural landscapes of the world: a more commercial form of organic agriculture and a peasant based more subsistence-oriented traditional agriculture. In this article, the agroecological features of organic agriculture as practiced in North America and Europe, and of traditional agriculture involving millions of small farmers and peasants in the developing world, are described with emphasis on their contribution to food security, conservation/ regeneration of biodiversity, and natural resources and economic viability. 1. Introduction In July 2003, the International Commission on the Future of Food and Agriculture published the Manifesto on the Future of Food. This report warns that corporately controlled, agrochemically based, monocultural, export-oriented agronomic systems are negatively impacting public health, ecosystem intensity, food quality, traditional rural livelihoods, and indigenous and local cultures, while accelerating indebtedness among millions of farmers and their separation from lands that have historically fed communities and families. The growing push toward http://greenplanet.eolss.net.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/EolssLogn/mss/C10/E5-15A.. -

Understanding Mountain Soils

2015 In every mountain region, soils constitute the foundation for agriculture, supporting essential ecosystem functions and food security. Mountain soils benefit not only the 900 million people living in the world’s mountainous areas but also billions more living downstream. Soil is a fragile resource that needs time to regenerate. Mountain soils are particularly susceptible to climate change, deforestation, unsustainable farming practices and resource extraction methods that affect their fertility and trigger land degradation, desertification and disasters such as floods and landslides. Mountain peoples often have a deep-rooted connection to the soils they live on; it is a part of their heritage. Over the centuries, they have developed solutions and techniques, indigenous practices, knowledge and sustain- able soil management approaches which have proved to be a key to resilience. This publication, produced by the Mountain Partnership as a contribution to the International Year of Soils 2015, presents the main features of mountain soil systems, their environmental, economic and social values, the threats they are facing and the cultural traditions concerning them. Case studies provided by Mountain Partnership members and partners around the world showcase challenges and opportunities as well as lessons learned in soil management. This publication presents a series of lessons learned and recommendations to inform moun- Understanding Mountain soils tain communities, policy-makers, development experts and academics who support sustainable -

Biodiverse Farming Produces More

GRAIN — BIODIVERSE FARMING PRODUCES MORE http://www.grain.org/es/article/entries/260-biodiverse-fa... Inicio › Archivo › Seedling › Publicaciones › Seedling - October 1997 › BIODIVERSE FA "ING PRODUCES MORE BIODIVERSE FARMING PRODUCES MORE GRAIN | () octubre 1997 | Seedling - October 1997 October 1997 BIODIVERSE FAR"ING PRODUCES MORE GRAIN Biodiversity-based farming systems have always proven their worth to the communities that developed them. But proponents of these systems have had difficulty convincing the formal agricultural research network and industrial agriculturists that such farming practices are more effective than industrial agriculture especially for local food security. In recent years, however, a wealth of documented evidence has been accumulated making the case for biodiverse farming. Such studies demonstrate that it can compete with industrial agriculture in terms of productivity and that biodiverse farming offers the important additional advantages of sustainability and risk reduction. GRAIN examines the evidence that the formal sector can no longer ignore. Even in the face of widespread criticism of the ecological havoc and health threats it poses, industrial agriculture is being thrust ever -ore *orcefully upon a sceptical global ,ublic. Industry and government officials alike are using scaremongering tactics about the population explosion to -anufacture acceptance of further intensified, chemical- dependent farming. 3his vision of agriculture depicts industrial production o* a *ew farm ,roducts produced largel/ by the world's biggest agricultural exporters, such as the %S and the EU. Many countries +ould depend on international -arkets for their food supplies, +hich would undermine local food security and cause social disintegration0 Meanwhile, advocates of sustainable. biodiverse farming systems argue that such systems are far more productive than is generally recognised and that they offer an alternative strateg/ for intensification with far greater long-term sustainability. -

Best Practices Using Indigenous Knowledge

Best Practices using Indigenous Knowledge Karin Boven (Nuffic) Jun Morohashi (UNESCO/MOST) (editors) Photographs on front cover: • Man manufacturing rattan handicrafts, China – Centre for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge (CBIK) • Women with adapted clay pots, Kenya – Robert E. Quick • Traditional healer teaching youngsters about medicinal plants, Suriname – Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) Keywords: • Indigenous knowledge • Best practices • Poverty alleviation • Sustainable development November 2002 A joint publication by: Nuffic, The Hague, The Netherlands, and UNESCO/MOST, Paris, France Contact: Nuffic-OS/IK Unit P.O. Box 29777 2502 LT The Hague The Netherlands Tel.: +31 70 4260321 Fax: +31 70 4260329 E-mail: [email protected], website www.nuffic.nl/ik-pages © 2002, Nuffic, The Hague, The Netherlands, and UNESCO/MOST, Paris, France. All rights reserved. ISBN: 90-5464-032-4 Materials from this publication may be reproduced and translated, provided the authors, publisher and source are acknowledged. The editors would appreciate receipt of a copy. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of Nuffic and/or UNESCO/MOST. Layout and printing: Nuffic–OS/IK Unit and PrintPartners Ipskamp B.V. Contents Note from the editors ...........................................................................6 1. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................10 1.1. Cooperation in the field of indigenous knowledge.......................10 1.1.1. Nuffic .........................................................................10 -

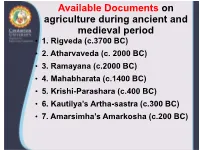

Available Documents on Agriculture During Ancient and Medieval Period • 1

Available Documents on agriculture during ancient and medieval period • 1. Rigveda (c.3700 BC) • 2. Atharvaveda (c. 2000 BC) • 3. Ramayana (c.2000 BC) • 4. Mahabharata (c.1400 BC) • 5. Krishi-Parashara (c.400 BC) • 6. Kautilya’s Artha-sastra (c.300 BC) • 7. Amarsimha’s Amarkosha (c.200 BC) Available Documents on agriculture during ancient and medieval period… • 8. Patanjali’s Mahabhasya (c.200 BC) • 9. Sangam literature (Tamils) (200 BC- 100 AD) • 10. Agnipurana (c.400 AD) • 11. Varahamihir’s Brihat Samhita (c. 500 AD) • 12. Kashyapiya’s Krishisukti (c.800Ad) • 13. Surapala’s Vriksh-Ayurveda (c.1000 AD) • 14. Chavun-daraya’s Lokopakaram (1025 AD) Available Documents on agriculture during ancient and medieval period… • 15. Someshwardeva’s Manasollasa (1131 AD) • 16. Saranghara’s Upavanavioda (c.1300 AD) • 17. Bhava Prakasha’s Nighantu (c.1500 AD) • 18. Chakrapani Mitra’s Viswavallbha (c.1580 AD) • 19. Dara Shikoh’s Nuskha Dar Fanni-Falahat (c.1650 Ad) • 20. Jati Jaichand’s dairy (1658-1714 AD) • 21. Anonymous Rajasthani Manuscript (1877 AD) • 22. Watt’s Dictionary of Economic Products of India (1889-1893 AD) GIAHS • Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS), as defined by the FAO are: "Remarkable land use systems and landscapes which are rich in globally significant biological diversity evolving from the co-adaptation of a community with its environment and its needs and aspirations for sustainable development". Examples of GIAHS 1. Mountain rice terrace agro-ecosystems • Mountain rice terrace systems with integrated forest use and/ or combined agro-forestry systems, such as: • agroforestry vanilla system in Pays Betsileo, Betafo and Mananara regions in Madagascar; • the Ifugao rice terraces in the Philippines; • These systems also include integrated rice-based systems (e.g. -

Clark L. Erickson

3-26-2021 Clark L. Erickson CURRICULUM VITAE CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Anthropology 3260 South Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6398 tel. (215) 898-2282 fax (215) 898-7462 email: [email protected] homepage: http://www.sas.upenn.edu/anthro/people/faculty/cerickso EDUCATION 1976 B.A. in Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. 1980 A.M. in Anthropology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. 1988 Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. RESEARCH INTERESTS My research focuses on indigenous knowledge, cultural landscape creation and management, biodiversity, sustainable lifeways, and environmental management. My Andean and Amazonian research applies the perspectives of landscape archaeology and historical ecology to understand the long, complex human history of the environment and cultural activities that have shaped the Earth. I also am involved in inter-school collaborative research and teaching with the Digital Media Design Program of the Department of Computer and Information Science in School of Engineering, the Historic Preservation Program and the Department of Landscape Architecture in School of Penn Design. CURRENT ACADEMIC POSITION 1988 – present University of Pennsylvania Professor of Anthropology (2011 – present); Associate Professor of Anthropology (1995– 2011); Assistant Professor (1988-1995). Affiliated faculty: Graduate Group Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World (2005 – present); Historic Preservation Faculty in Penn Design (2004 – present). 1988 – present University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Curator; Curator-In-Charge (2012-present), Associate Curator (1995-2012); Assistant Curator (1988-1995); American Section. BOOKS 2009 (with James E. Snead and J. Andrew Darling) Landscapes of Movement: The Anthropology of Trails, Paths, and Roads. -

INSIDE: LTA Update Led by Michael Woodhouse

Combatting climate change Funded by the Douglas Bomford Trust, Lisa Bunclark spent this summer in a small Himalayan village Importance of CPD INSIDE: LTA Update Led by Michael Woodhouse. IAgrE with feature articles on CVT Council debates whether CPD developments and ISO couplings events are fit for purpose IAgrE Professional Journal www.iagre.org Volume 64, Number 4 Winter 2009 Biosystems Engineering The Managing Editor of Biosystems Engineering, Dr Steve Parkin, Biosystems Engineering, owned by IAgrE, has kindly summarised some of the papers published in the last and the Official Scientific Journal of three issues which he thinks may be of interest to IAgrE members EurAgEng, is published monthly with Biosystems Engineering occasional special issues. Volume 103, Issue 4, August 2009, Pages 397-408 Modelling of material handling operations using controlled traffic D.D. Bochtis, C.G. Sørensen, R.N. Jørgensen, O. Green University of Aarhus, Department of Agricultural Engineering, Tjele, Denmark University of Southern Denmark, Biotechnology and Environmental Technology, Odense M, Denmark The development of a discrete-event model for the prediction of travelled dis- tances of a machine operating in material handling operations using the con- cept of CTF is presented. The model is based on the mathematical formulation of the discrete events regarding the motion of the machine when performing the fieldwork pattern. To evaluate the model two slurry application experiments were designed. The experiments involved registering the position and monitor- ing the application status of the slurry applicator. Validation showed that the model could adequately predict the motion pattern of machinery operating in CTF. Prediction errors of total distance travelled, were 0.24% and 1.41% for the 2 experimental setups. -

Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook

CLIMATESMART AGRICULTURE Sourcebook FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS 2013 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107720-7 (print) E-ISBN 978-92-5-107721-4 (PDF) © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

The Democratic and Sacred Nature of Agriculture

Environ Dev Sustain (2012) 14:335–346 DOI 10.1007/s10668-011-9327-3 The democratic and sacred nature of agriculture Evaggelos Vallianatos Received: 2 August 2011 / Accepted: 15 September 2011 / Published online: 27 September 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract ‘Sustainable’ agriculture is a relative recent invention. It is a salvage operation designed to undo some of the harm of agribusiness, which nearly wiped out farming as a way of life. Sustainable agriculture tries to restore methods of farming and values that satisfy present needs for food without compromising the food for future generations. Sustainable farming, however, remains experimental and on the fringes of society and science. It includes all kinds of farming practiced by peasants, small-scale family farmers, organic farmers as well as large farmers. In what follows, I am showing, first, farming is or becomes sustainable when two things prevail: First, it is democratic, spread throughout the land in the form of family farming while the difference in size among farms is modest at best. Second, farming is sustainable when it draws its inspiration and methods not merely from the most advanced ecological science but from ancient agrarian cultures. I briefly highlight the case of ancient Greek farming as having the virtues of sustainability: that of equity and democracy. In our times, however, agribusiness and animal farming fail the criteria of sustainability. Keywords Democracy Industrialization Agribusiness Large farms Sustainability Sacred agriculture OrganicÁ farming AnimalÁ farms NatureÁ Á Á Á Á Á 1 Introduction The dust bowl of the 1930s is symbolic of the violence unleashed in rural America and the rest of the world by industrialized farming, mechanizing what used to be a way of life on the land into a factory for the extraction of profits.