Arxiv:1810.00224V2 [Q-Bio.PE] 7 Dec 2020 Humanity Is Increasingly Influencing Global Environments [195]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Behavior: Applying Behavioral Ecology to Wildlife Conservation and Management Edited by Oded Berger-Tal and David Saltz Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04010-6 - Conservation Behavior: Applying Behavioral Ecology to Wildlife Conservation and Management Edited by Oded Berger-Tal and David Saltz Frontmatter More information Conservation Behavior Applying Behavioral Ecology to Wildlife Conservation and Management Conservation behavior assists the investigation of species endangerment associated with managing animals impacted by anthropogenic activities. It employs a theoretical framework that examines the mechanisms, development, function and phylogeny of behavior variation in order to develop practical tools for preventing biodiversity loss and extinction. Developed from a symposium held at the International Congress for Conservation Biology in 2011, this is the first book to offer an in-depth, logical framework that identifies three vital areas for understanding conservation behavior: anthropogenic threats to wildlife, conservation and management protocols, and indicators of anthropogenic threats. Bridging the gap between behavioral ecology and conservation biology, this volume ascertains key links between the fields, explores the theoretical foundations of these linkages, and connects them to practical wildlife management tools and concise applicable advice. Adopting a clear and structured approach throughout, this book is a vital resource for graduate students, academic researchers, and wildlife managers. ODED BERGER-TAL is a senior lecturer at the Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology of Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. His research centers upon the integration of behavioral ecology into wildlife conservation and management. DAVID SALTZ is a Professor of Conservation Biology at the Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology, and the director of the Swiss Institute for Desert Energy and Environmental ResearchofBenGurionUniversityoftheNegev, Israel. His research focuses on wildlife conservation and management. -

Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E. Hepner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hepner, Megan E., "Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Megan E. Hepner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Frank Muller-Karger, Ph.D. Christopher Stallings, Ph.D. Steve Gittings, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31st, 2017 Keywords: Species richness, biodiversity, functional diversity, species traits Copyright © 2017, Megan E. Hepner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to my major advisor, Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, who provided opportunities for me to strengthen my skills as a researcher on research cruises, dive surveys, and in the laboratory, and as a communicator through oral and presentations at conferences, and for encouraging my participation as a full team member in various meetings of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and other science meetings. -

Iplant Collaborative Taking Plant Biology Into Cyberspace by Janni Simner and Susan Mcginley Leslie Johnston

The iPlant Collaborative Taking plant biology into cyberspace By Janni Simner and Susan McGinley Leslie Johnston Richard Jorgensen, lead investigator and director of the iPlant Collaborative, surrounded by petunias used in gene expression studies. he National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded a environmental changes; how plants have evolved in the past and University of Arizona–led team $50 million to create a global their potential to evolve in the future; and how plants live together Tcenter and computer cyberinfrastructure to answer plant with other organisms in ecosystems. biology’s grand challenge questions, which no single research entity iPlant’s team of plant biologists, computer scientists, information in the world currently has the capacity to address. scientists, mathematicians and social scientists will set about The project will unite plant scientists, computer scientists and building a “Discovery Environment”—a cyberinfrastructure—to information scientists from around the world for the first time to answer those questions in partnership with the community’s grand provide answers to questions of global importance and to advance challenge teams. knowledge in all of these fields. The iPlant center will be located in and administered through Dubbed the iPlant Collaborative, the five-year project is the UA’s BIO5 Institute in Tucson. BIO5 was founded to encourage potentially renewable for a second five years for a total of $100 collaboration across scientific disciplines, accelerate the pace of million. scientific discovery and develop innovative solutions to society’s “This global center is going to change the way we do science,” most complex biological problems. The iPlant Collaborative will says UA plant sciences professor and BIO5 Institute member create both a physical center and a virtual computing space where Richard Jorgensen, who is the lead investigator and director of researchers can communicate and work together as they share, the iPlant Collaborative. -

G2 Phase Cell Cycle Regulation by E2F4 Following Genotoxic Stress

G2 Phase Cell Cycle Regulation by E2F4 Following Genotoxic Stress by MEREDITH ELLEN CROSBY Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis Advisor: Dr. Alex Almasan Department of Environmental Health Sciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2006 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of ______________________________________________________ candidate for the Ph.D. degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………….1 LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………….5 LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………...7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………….8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………10 ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...15 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. CELL CYCLE REGULATION: HISTORICAL OVERVIEW………………...17 1.2. THE E2F FAMILY OF TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS……………………….22 1.3. E2F AND CELL CYCLE CONTROL 1.3.1. G0/G1 Phase Transition………………………………………………….28 1.3.2. S Phase…………………………………………………………………...28 1.3.3. G2/M Phase Transition…………………………………………………..30 1.4. -

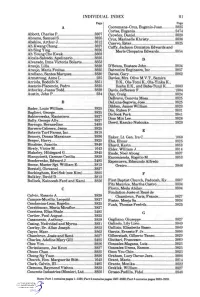

Individual Index

INDIVIDUAL INDEX Bl Page Page A Cooremans-Cruz, Eugenio Juan 3825 Cortes, Eugenia 2474 Abbott, Charles P 3807 Crowley, Daniel 3820 Abrams, Samuel S 3825 Cruz, Marinelle Khristy 3836 Abshire, Arthur J 3812 Cuervo, Ester 3825 Ah Kwang Chang 3827 Cuffy, Jackson Ormiston Edwards and Ah Sing Ying 3826 Merle Cleopatra Edwards 38J54 Ah Young Cho Kwak 3803 Alcala-Salcedo, Apolinario 3825 D Alvarado, Irma Victoria Bolarte 3853 Araujo,Lilia 3828 D'Souza, Eustace John 3824 Araujo, Maria Freitas 3825 Datronics Engineers, Inc 3857 Arellano, Santos Marquez 3830 Daves, Gary 3862 Armstrong, Anne L 235 Davies, Mrs. Olive M.V.T., Samira Arriola, Rodolfo N 3851 D.K., Ola-Tomi K., Ola-Yinka K., Asencio-Placencio, Pedro 3825 Ilesha E.K., and Baba-Tunji K 3803 Atherley, Juana Todd 3829 Davis, Jefferson F 1304 Austin, John P 234 Day, Craig 3824 DeBravo, Cenovia Mesa 3825 B DeLuna-Segovia, Jose 3825 Dibben, James William 3823 Bader, Louis William 3825 Din, Ruben P 3831 Baglieri, George 3825 Do Sook Park 3841 Bakierowska, Kazimiera 3827 Dom Min Lee 3826 Bally, George Ally 3827 Dowd, Kazuko Nishioka 3820 Barengo, Bernardino 2485 Barrera-Cabrera, Jesus 3825 Batavia Turf Farms, Inc 3818 • ^- • E Benney, Donna Marainne 3836 Eaker, Lt. Gen. IraC 1060 Berger, Harry 3825 Eha,Elmar 3825 Binabise, Juanita 3840 Ehard,Karin 3858 Birely, Victor M 1643 Elder, William J 3814 Blakeley, Hildegard G 3845 Emde, Noel Abueg 3837 Blanquicett, Carmen Cecilia 3859 Encomienda, Rogelio M 3853 Bonderenko, Edward J 2485 Espenueva, Edmundo Alfredo Boone, Master Sgt. William E 3813 Oreiro -

Size Composition, Growth, Mortality and Yield of Alectis Alexandrinus (Geoffory Saint-Hilaire) in Bonny River, Niger Delta, Nigeria

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 8 (23), pp. 6721-6723, 1 December, 2009 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB ISSN 1684–5315 © 2009 Academic Journals Short Communication Size composition, growth, mortality and yield of Alectis alexandrinus (Geoffory Saint-Hilaire) in Bonny River, Niger Delta, Nigeria S. N. Deekae1, K. O. Chukwu1 and A. J. Gbulubo2 1Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Environment, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port-Harcourt Rivers State, Nigeria. 2African Regional Aquaculture Centre, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, P.M.B.5122, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Accepted 3 November, 2008 A twelve month study on the size composition, growth, mortality and yield of Alectis alexandrinus revealed a length range of 11.5 - 33.8 cm (standard length). Employing the length frequency method in the FISAT II package gave the following results for the Von Bertanlanffy growth parameters: L = 35.23, K = 0.680, to = 0.3214 and = 2.926. The total mortality (Z) was 2.47, natural mortality (M) 1.39 and fishing mortality (F) 1.08.The relative biomass per recruit (knife edge selection) was Lc/ L = 0.05, E10 = 0.355 and E50 = 0.278. Although the exploitation rate (E) was 0.44 the Emax was 0.421 indicating moderate exploitation of the fish in Bonny River. There is room for increased effort in the fisheries. Key word: Size, growth, mortality, yield, Alectis alexandrinus. INTRODUCTION Alectics alexandrinus is one of the commercially valuable tions or species into categories of high, medium low and fishes in the gulf of Guinea, which could be relevant in very low resilience or productivity have been suggested sport fishing as obtainable in places like Hawaii (Pamela et al., 2001; Musick, 1999). -

Female Fellows of the Royal Society

Female Fellows of the Royal Society Professor Jan Anderson FRS [1996] Professor Ruth Lynden-Bell FRS [2006] Professor Judith Armitage FRS [2013] Dr Mary Lyon FRS [1973] Professor Frances Ashcroft FMedSci FRS [1999] Professor Georgina Mace CBE FRS [2002] Professor Gillian Bates FMedSci FRS [2007] Professor Trudy Mackay FRS [2006] Professor Jean Beggs CBE FRS [1998] Professor Enid MacRobbie FRS [1991] Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell DBE FRS [2003] Dr Philippa Marrack FMedSci FRS [1997] Dame Valerie Beral DBE FMedSci FRS [2006] Professor Dusa McDuff FRS [1994] Dr Mariann Bienz FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Angela McLean FRS [2009] Professor Elizabeth Blackburn AC FRS [1992] Professor Anne Mills FMedSci FRS [2013] Professor Andrea Brand FMedSci FRS [2010] Professor Brenda Milner CC FRS [1979] Professor Eleanor Burbidge FRS [1964] Dr Anne O'Garra FMedSci FRS [2008] Professor Eleanor Campbell FRS [2010] Dame Bridget Ogilvie AC DBE FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Doreen Cantrell FMedSci FRS [2011] Baroness Onora O'Neill * CBE FBA FMedSci FRS [2007] Professor Lorna Casselton CBE FRS [1999] Dame Linda Partridge DBE FMedSci FRS [1996] Professor Deborah Charlesworth FRS [2005] Dr Barbara Pearse FRS [1988] Professor Jennifer Clack FRS [2009] Professor Fiona Powrie FRS [2011] Professor Nicola Clayton FRS [2010] Professor Susan Rees FRS [2002] Professor Suzanne Cory AC FRS [1992] Professor Daniela Rhodes FRS [2007] Dame Kay Davies DBE FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Elizabeth Robertson FRS [2003] Professor Caroline Dean OBE FRS [2004] Dame Carol Robinson DBE FMedSci -

Can You Make Morphometrics Work When You Know the Right Answer? Pick and Mix Approaches for Apple Identification

RESEARCH ARTICLE Can you make morphometrics work when you know the right answer? Pick and mix approaches for apple identification 1¤ 2 1 Maria D. ChristodoulouID , Nicholas Hugh Battey , Alastair CulhamID * 1 University of Reading Herbarium, Harborne Building, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, United Kingdom, 2 School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Whiteknights Reading, United Kingdom a1111111111 ¤ Current address: Department of Statistics, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Morphological classification of living things has challenged science for several centuries and has led to a wide range of objective morphometric approaches in data gathering and analy- sis. In this paper we explore those methods using apple cultivars, a model biological system OPEN ACCESS in which discrete groups are pre-defined but in which there is a high level of overall morpho- Citation: Christodoulou MD, Battey NH, Culham A logical similarity. The effectiveness of morphometric techniques in discovering the groups is (2018) Can you make morphometrics work when you know the right answer? Pick and mix evaluated using statistical learning tools. No one technique proved optimal in classification approaches for apple identification. PLoS ONE on every occasion, linear morphometric techniques slightly out-performing geometric 13(10): e0205357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. (72.6% accuracy on test set versus 66.7%). -

Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science 2013

News PPWSPlant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science www.ppws.vt.edu 2013 Greetings to our alumni, colleagues, and friends! We have had a busy year in the Department of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science. We are pleased to share an update of our accomplishments with you. In the fall we welcomed new faculty member Dr. Xiaofeng Wang whose research interests include plant virology. We would like to congratulate the graduate students who successfully completed their degrees. We had a total of 12 graduations in the past academic year. In Fall 2012 we debuted a new student-organized mini symposium that now includes a poster competition and travel awards for outstanding graduate students. Our popular Agricultural Research and Extension Center and Ag Industry tour visited the Alson H. Smith, Jr. center in Winchester, the Southern Piedmont AREC in Blackstone, and the Eastern Virginia AREC in Warsaw last fall to provide students a first- Elizabeth Grabau, hand view of our applied research programs. We were pleased to be able to honor department head Scott Hagood as an emeritus professor of weed science during this past year. At the annual college alumni awards celebration in March we also recognized two outstanding PPWS alumni, Anne Dorrance and David McCall. As we look ahead to the coming year, we hope to visit with many of you at meetings and conferences. Please keep us informed of your news and accomplishments. We also invite you stop by the department whenever your travel finds you in the Blacksburg area. Elizabeth Grabau, department head CALS Alumni Awards Anne Dorrance (Ph.D. -

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Iii. Administración Local

BOCM BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID Pág. 468 LUNES 21 DE MARZO DE 2011 B.O.C.M. Núm. 67 III. ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL AYUNTAMIENTO DE 17 MADRID RÉGIMEN ECONÓMICO Agencia Tributaria Madrid Subdirección General de Recaudación En los expedientes que se tramitan en esta Subdirección General de Recaudación con- forme al procedimiento de apremio, se ha intentado la notificación cuya clave se indica en la columna “TN”, sin que haya podido practicarse por causas no imputables a esta Administra- ción. Al amparo de lo dispuesto en el artículo 112 de la Ley 58/2003, de 17 de diciembre, Ge- neral Tributaria (“Boletín Oficial del Estado” número 302, de 18 de diciembre), por el presen- te anuncio se emplaza a los interesados que se consignan en el anexo adjunto, a fin de que comparezcan ante el Órgano y Oficina Municipal que se especifica en el mismo, con el obje- to de serles entregada la respectiva notificación. A tal efecto, se les señala que deberán comparecer en cualquiera de las Oficinas de Atención Integral al Contribuyente, dentro del plazo de los quince días naturales al de la pu- blicación del presente anuncio en el BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID, de lunes a jueves, entre las nueve y las diecisiete horas, y los viernes y el mes de agosto, entre las nueve y las catorce horas. Quedan advertidos de que, transcurrido dicho plazo sin que tuviere lugar su compare- cencia, se entenderá producida la notificación a todos los efectos legales desde el día si- guiente al del vencimiento del plazo señalado. -

IPBES Global Assessment Chapter 4 - Supplementary Materials

IPBES Global assessment Chapter 4 - Supplementary materials Contents Appendix 4.1 – Supporting materials to section 1 .................................................................................. 2 A4.1.1 Methodology for Literature Search, Review and Analysis ...................................................... 2 General ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Literature Search and Supplementation ......................................................................................... 2 Literature metadata analysis .......................................................................................................... 4 A4.1.2 – Extended figures and tables to section 1............................................................................ 13 Appendix 4.2 - Supporting materials to section 2................................................................................. 15 A4.2.1 The main interrelations and feedbacks between hierarchical levels that are important for biodiversity future (extended materials, Box 4.2.1) ......................................................................... 15 INTRAPOPULATION and INTRASPECIFIC DIVERSITY ...................................................................... 15 INDIVIDUAL SPECIES...................................................................................................................... 17 SPECIES DIVERSITY .......................................................................................................................