Cultural Reviews Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Cumings, the Korean

THE KOREAN WAR clan A9:4 A HISTORY ( toot ie let .•-,• ••% ale draa. • 0%1. • .„ \ •r• • • di 11111 1 41'• di• wrsn..."7 • -s. ve,„411p- • dm0 41N-Nitio6 u". •••• -- 411 • ose - r 011.,r•rw••••••• ate,tit 0it it& ado tem.........,111111111nrra° 1 40 Of ••••••—•S‘ 11••••••••••••••• 4,1••••••• o CUMINGS' •IP • AABOUTBOUT THE AAUTHORUTHOR BRUCE CCUMINGSUMINGS is the Gustavus F. and Ann M.M. Swift DistinguishedDistinguished Service ProfessorProfessor inin HistoryHistory atat the University ofof ChicagoChicago and specializesspecializes inin modernmodem KoreanKorean history,history, internationalinternational history,history, andand EastEast AsianAsian–American–American relations. 2010 Modern LibraryLibrary EditionEdition CopyrightCopyright CD© 2010 by Bruce Cumings Maps copyrightcopyright ©0 2010 by Mapping Specialists AllAll rights reserved. Published in the United States by Modern Library,Library, an imprintimprint ofof TheThe Random HouseHouse PublishingPublishing Group,Group, a division ofof RandomRandom House, Inc., New York.York. MODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER DesignDesign areare registeredregistered trademarkstrademarks ofof RandomRandom House,House, Inc.Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGINGCATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION-IN-PUBLICATION DATADATA Cumings,Cumings, Bruce TheThe KoreanKorean War/BruceWar/Bruce Cumings. p. cm.cm.—(A—(A modern librarylibrary chronicleschronicles book)book) eISBN:eISBN: 978-0-679-60378-8978-0-679-60378-8 1.1. Korean War, 1950-1953.1950–1953. 22. KoreanKorean War, 19501950-1953—United–1953—United States. 3. Korean War,War, 19501950-1953—Social–1953—Social aspectsaspects—United—United States. I. Title. DS918.C75D5918.C75 2010 951 951.904 .9042—dc22′2—dc22 2010005629 2010005629 www.modernlibrary.comwww.modemlibrary.com v3.0 CHRONOLOGY 2333 B.C.B.C. Mythical Mythical founding ofof thethe Korean nationnation byby Tangun and hishis bear wifewife. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

Neasialookinside.Pdf

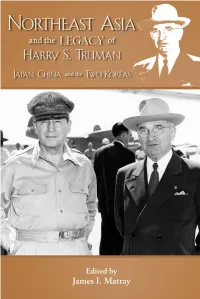

The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in Northeast Asia The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 8 Based on the Eighth Truman Legacy Symposium The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas May 2010 Key West, Florida Edited by James I. Matray Copyright © 2012 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman and General MacArthur at Wake Island, October 15, 1950 (HSTL 67-434). Cover design: Katie Best Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Truman Legacy Symposium (8th : 2010 : Key West, Fla.) Northeast Asia and the legacy of Harry S. Truman : Japan, China, and the two Koreas / edited by James I. Matray. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; volume 8) “Based on the eighth Truman Legacy Symposium, The legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the two Koreas, May, 2010, Key West, Florida.” Includes index. 1. East Asia—Relations—United States—Congresses. 2. United States—Relations— East Asia—Congresses. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1945–1953—Congresses. 4. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Congresses. I. Matray, James Irving, 1948–, editor of compilation. II. Title. DS518.8.T69 2010 327.507309'044—dc23 2012011870 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48– 1992. To Amanda Jane Matray A Master Teacher Contents Illustrations .........................................ix Preface ..............................................xi General Editor’s Preface .............................xiii Introduction .........................................1 Mild about Harry— President Harry S. -

An Analysis of Selected Fiction, Non-Fiction, And

"PLUNGED BACK WITH REDOUBLED FORCE": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FICTION, NON-FICTION, AND POETRY OF THE KOREAN WAR A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts John Tierney May, 2014 "PLUNGED BACK WITH REDOUBLED FORCE": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FICTION, NON-FICTION, AND POETRY OF THE KOREAN WAR John Tierney Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Faculty Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Patrick Chura Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Department Coordinator Date Dr. Joseph F. Ceccio _______________________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii DEDICATION To Jonas and his grand empathy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Ji Young for her support and patience these three years. Veronica and Patrick for the diversions. Thanks also to Dr. Mary Biddinger for her advice and encouragement with the writing process, to Dr. Patrick Chura for his time and vote of confidence, to Dr. Joseph Ceccio for his time and advice, and to Dr. Hillary Nunn for her seminar in literary criticism and for her help with editing. A million thanks to Craig Blais, Colleen Tierney, and everyone else who listened to my ideas at the conception of this project. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………………..1 II. IMPERIAL AMERICA AND THE PREDOMINANCE IN MILITARY POWER IN THE KOREAN WAR……………………………………………………………………..........8 Background…………………………………………………………………………........10 Military Readiness…………………………………………………………………….15 Demeanor and Performance………………..…………………………….............18 Brutal Methods…...……………………………………………………………………..20 III. CHAOS IN THE FATHERLAND……………………………………………………………….30 Background.………………………………………………………………………………31 IV. -

Chinese Experience of the Korean War

> Review Chinese experience of the Korean War Ha Jin. 2004. War Trash. New York: Pantheon Books, 352 pages, ISBN 0 375 42276 5 oner learns to read, which in the muted armed only with bamboo spears and tones of the novel, brings satisfaction to shouts of ‘Mansei!’ (p.187). This epi- the narrator. Rarely, however, are emo- sode, like other repudiations of proletar- tions overplayed. While homesickness ian Korean nationalism, demonstrated among the troops receives sympathetic a deep need among the prisoners for treatment, this text seldom wallows in images of a dominant North Korea, as sentimentality. seen in the accompanying drawing. In the midst of prison camp struggles, Ha Like the 2,000,000 mainland Chinese Jin credits the Americans their share of who were thrust into Korea as ‘volun- brutality, but does not spare the prison- teers’, the narrator encounters an array ers for their own folly. Preparing for an of nationalities, testifying to Korea’s all-out rumble with the guards, Chinese inundation by foreign soldiers. Ameri- prisoners create signs reading ‘Respect cans appear as solicitous doctors, embat- the Geneva Convention!’ even as they tled black soldiers sympathetic to com- sharpen their shanks. munist doctrine, and angry sergeants capable of torture. No one communi- The Chinese-North Korean camara- cates particularly well, and language derie that pervades War Trash exists barriers appear frequently, reminding today only in propaganda artefacts and the reader that, for the Chinese troops wartime kitsch hawked by vendors who trudged across the Yalu River and along the northern bank of the Yalu into the pockmarked netherworld of the River. -

War Trash Free

FREE WAR TRASH PDF Ha Jin | 352 pages | 01 Aug 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9781400075799 | English | New York, United States War Trash by Ha Jin: | : Books A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality study guides that feature detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, quotes, and essay topics. War Trash Ha Jin. Transform this Plot Summary into a Study Guide. War Trash is a historical novel by Ha Jin. The book received widespread critical acclaim upon publication and received a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Ha Jin is the pen name War Trash Jin Xuefei. He is a short story writer, English professor, poet, and novelist. He typically writes about China in English for political reasons. He is best known for his historically accurate world building and his imaginative writing. War Trash begins in during the Korean War. He does not like Communism, but he is forced to accept it as a political reality. As a teenager, he trained as a cadet at the Huangpu Military Academy. Before the Communists seized control of China, the Nationalists controlled the academy; Yuan enjoyed serving under them. Thanks to political pressure, he must now support North Korea in the war effort against South Korea. North Korea has Chinese backing. The academy sends him to Korea where he must serve in the th Division because, unlike most Chinese officers, he speaks and reads enough English to act as a translator. Yuan wants to go home and follow his own political beliefs. He does not expect Tao to wait for him because he has no idea when he will be home again. -

Chinese Soldiers As Prisoners in Korea: Ideological Enigma

Chinese Soldiers as Prisoners in Korea: Ideological Enigma Chinese Soldiers as Prisoners in Korea: Ideological Enigma Bruce Jacobs The handling and dispositions of enemy prisoners of war, as a national responsibility, established itself on the front-burner of America’s attention span, as a crucial sidebar to the war in Iraq. Controversy has, rightly or wrongly, also characterized American views of the military prison facility at Guantanamo Navy Base in Cuba as a detention center. The widely-publicized events at the U.S.-run Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad focused worldwide attention on how we appeared to be carrying out the responsibility which evolves upon a country with prisoners in its custody. During 2005 the Army Combat Studies Institute took a hard look at the subject of “detainee doctrine and experience” noting in the introduction that, “the perception of just treatment held by citizens of our nation and, to a great extent the world at large, have been and are being shaped by the actions of the US Army, both in the commission of detainee treatment but also, and more importantly, in the way the Army addresses its institutional shortcomings.” In tracing the history of this sometimes seriously misunderstood subject the author of The Road to Abu Ghraib1 revisits the U.S. experience in the prisoner-of-war issues of the Korean War. Mismanagement of prisoners taken by United Nations Command troops in the war should be looked at in the light of the reminder by the author of the study that, “the surprise and rapidity of the North Korean invasion of South Korea forestalled any effort to plan for the care of EPWs2 on the scale necessary.”3 In this essay we will explore some of the unusual circumstances, particularly those of the Chinese prisoners of war, which would lead to subsequent and perhaps inevitable allegations of prisoner abuse in the UNC prison compounds. -

Settler Modernity¬タルs Spatial Exceptions: the US POW Camp

Settler Modernity’s Spatial Exceptions: The US POW Camp, Metapolitical Authority, and Ha Jin’s War Trash Jodi Kim American Quarterly, Volume 69, Number 3, September 2017, pp. 569-587 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/670058 Access provided by University of Hawaii @ Manoa (19 Sep 2017 21:28 GMT) Settler Modernity’s Spatial Exceptions | 569 Settler Modernity’s Spatial Exceptions: The US POW Camp, Metapolitical Authority, and Ha Jin’s War Trash Jodi Kim n October 2011 Secretary of State Hillary Clinton revealed in a policy plan titled “America’s Pacific Century” that the United States would “pivot” Ifrom the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific. In this plan, the Asia-Pacific is identified as the most crucial sphere of US influence in the twenty-first century and the region where US military resources will be concentrated. Yet even in the previous century, “The American Century,” even in the absence of such an explicit pivot, we witnessed a brutal concentration of military resources and violence. US imperial violence in Asia, previously rationalized under the sign of the Cold War, gets reanimated under the sign of “new global realities.” “America’s Pacific Century” posits that “in the last decade, our foreign policy has transitioned from dealing with the post–Cold War peace dividend to de- manding commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan. As those wars wind down, we will need to accelerate efforts to pivot to new global realities.” An “emerging China” is named as a new global reality, and the Asia-Pacific is identified as the United States’ “real 21st century opportunity,” an investment that will yield the greatest returns. -

On the Korean War POW in Ha Jin's War Trash Draft

Lee 1 Detention, Repatriation, Humanitarianism: On the Korean War POW in Ha Jin’s War Trash Draft – do not cite or circulate DCC Graduate Workshop April 17, 2013 Yumi Lee, [email protected] Ph.D Candidate, Dept. of English University of Pennsylvania Introduction Early in Ha Jin’s 2004 novel War Trash, the narrator Yu Yuan sits in an overcrowded prison compound on Koje Island, a small island off the southern coast of Korea. It is April 1951, and he and his fellow prisoners, soldiers of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, have been captured by UN forces during the Korean War. While Yu is determined to return home to China to take care of his aging mother and marry his sweetheart after the war is over, many of his erstwhile comrades have decided to refuse to return to China and instead throw in their lot with the Nationalist government-in-exile in Taiwan. When the prisoners are informed of the UN’s plan to proceed with individual screenings to determine whether each prisoner will return home or “forcibly” refuse repatriation, they are pressed to make their final decisions. Representatives of the Nationalist leadership in Yu’s compound urge their fellow prisoners in no uncertain terms to refuse repatriation, warning that they will surely be punished as traitors and failures should they choose to return home. “I don’t want to be tortured and butchered like a worthless animal,” one leader in the compound proclaims, “so I’ve decided to leave for the Free World, to wander Lee 2 as a homeless man for the rest of my life. -

Vanderbilt University 4829948

PRISONERS, DIPLOMATS, AND SABOTEURS: AN INTERNATIONAL HISTORY OF THE DIPLOMACY OF CAPTIVITY DURING AND FOLLOWING THE KOREAN WAR By Lu Sun Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2017 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Thomas A. Schwartz, Ph.D. Paul A. Kramer, Ph.D. Ruth Rogaski, Ph.D. Brett V. Benson, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. iii Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... iv Chapter Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ....................................................................................................................... 3 Approaches and Significance of the Study ........................................................................... 7 II. “Segregating” by Race, Rank, and Nationality: China’s Failed Ideological Indoctrination During the Korean War .................................................................................... 12 Atrocity Charges and Leniency Policy ............................................................................... 18 Battle for Ideological Supremacy ....................................................................................... -

Ha Jin's War Trash:1 Novel As Historical Evidence Historians Of

2005.04.01 Ha Jin’s War Trash:1 Novel as Historical Evidence John Shy, The University of Michigan ([email protected]) Historians of war and their readers invariably, some more than others, seek to know the reality of what it was like to be directly involved in war. John Keegan has discussed this urge and the difficulties of satisfying it in the long introduction to Face of Battle. Just as in- variably, they are frustrated by the evidence of that reality. Anyone who has ever been in- volved in the creation and maintenance of official records, so voluminous for war, is aware of how these records misrepresent the human reality. Accidentally, incidentally, deliber- ately, blatantly, subtly, record keepers omit, distort, and simply lie about what they might have set down in the record. After all, their concern at the moment is with simply keeping the record, not with its historical value. A smaller body of evidence is personal, written by people—usually men—who were themselves directly involved. But personal records, memoirs of war, also have their prob- lems. The writers are a peculiar, unrepresentative group. For whatever reason, they are a small minority of survivors who felt the urge to write about their experience after the event. Not too long ago, professors in graduate seminars advised their students to discount the values of memoir evidence. It was “fool’s gold,” the professors argued, full of tempting revelations not readily found in archival records, but riddled with the flaws of human memory, and weakened to an extent difficult for any reader to know by the natural human desire to tell the story that the writer wishes were true. -

War Trash and the Vagrants

Intercultural Communication Studies XXVII: 1 (2018) ZHU The Weightless of History: War Trash and The Vagrants ZHU Ying Macao Polytechnic Institute, Macao S.A.R., China Abstract: Departing from textual readings and focusing on the representations of activism, this essay attempts to present War Trash and The Vagrants as Ha Jin’s and Yiyun Li’s literary endeavors to give presence to the “weightless” mass whose voices in modern Chinese history have been intentionally dismissed or silenced. More importantly, Ha Jin and Yiyun Li, both writing in an adopted language —English— have engaged actively through their historical fiction in a “war” against any socio- political and ideological machinery of oppression and violence which, in turn, crashes one emotionally, mentally, and psychologically. The essay is divided into four sections: the first section introduces the two most renowned Chinese American writers in contemporary American literature — Ha Jin and Yiyun Li. The second section searches through War Trash for Ha Jin’s meaningful sleight-of-hand in fictionalizing and modernizing the “prison narrative”. The third section follows The Vagrants to unveil Yiyun Li’s carefully woven intertextuality and numerology. The last section looks back at Ha Jin’s and Li’s activism in their literary journey of, about, and beyond China. Keywords: Historical fiction, representation, activism 1. Introduction What’s madness but nobility of soul At odds with circumstance? — Theodore Roethke, “In a Dark Time” Having both learned English as a foreign language and published only in English, Ha Jin and Yiyun Li, two acclaimed contemporary Chinese American writers, have inarguably stretched our imaginative landscape to embrace seemingly alien/ Chinese yet universal experience.