Bruce Cumings, the Korean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Korean History SEM 1 AY 2017-2018

HH3020: Introduction to Korean History SEM 1 AY 2017-2018 Asst Prof Park Hyung Wook Contact: Phone: 6592 3565 / Office: HSS 05-14 / Email: [email protected] I. Course Description: This is a seminar course in the history of Korea, focusing on its modern part. Students will be able to study the major issues in the creation of the Korean nation, the national identity, the growth of its unique social and political structure, and the technological and industrial growth in the modern period. The primary subjects in the seminar include premodern development of the Korean nation and culture, the Japanese colonial era, the liberation after World War II, the Korean War, and the period after the mid-twentieth century when Koreans experienced the shock of their rapid industrialization and urbanization. Students will learn the dynamics of the Korean history which placed the country in the changing global landscape in the contemporary world. II. Course Design: There will be a three-hour seminar each week. For the first 40 minutes, the professor will introduce the day’s main subjects with certain points for further thinking. Then, some students will present their analysis of newspapers relevant to the week’s theme. The following hours will be used for group discussion based on the selected pre-class questions. Each group, before the end of the seminar, will present their discussion in front of other students. The result of the discussion should be uploaded in NTULearn. III. Course Schedule and Readings: The Course Readings: There are two kinds of readings, the required and the optional. -

Brothers at War Korean War Available

RESOURCES BOOK REVIEWS Brothers at War Korean War available. Where Jager departs from other histories of the The Unending Conflict in Korea Korean War are the next three shorter sections that bring the postarmi- stice conflict up to the present. Together, they account for two-fifths By Sheila Miyoshi Jager. of the main text. The first of these post-1953 sections covers what she considers to be the “Cold War era” in which rivalry and tensions be- New York: W.W. Norton, 2013 tween the two Koreas took place within the larger context of the Cold 608 pages, ISBN: 978-0393068498 , Hardback War, a period that ended in the late 1960s. With US-Soviet détente, the improvements in US-PRC relations, and the American withdrawal Reviewed by Michael J. Seth from Việt Nam, Washington’s focus on Korea shifted to stability rather than containment. At this point, the conflict became more of what the author calls a “local war,” a period of intense competition between Seoul lmost every author writing on and P’yŏngyang marked by violent incidents that had relatively little the Korean War states that it is global impact. A final part of the book deals with the period since the often, and aptly for Americans, early 1990s, when South Korea became a democratic society and North Acalled the “forgotten war.” Sheila Miy- Korea had lost the contest for legitimacy. The conflict then entered a oshi Jager in her book Brothers at War: phase in which the main concerns of Seoul, Washington, and the in- The Unending Conflict in Korea provides ternational community were over P’yŏngyang’s nuclear weapons and one of the most persuasive cases for its the repercussions of what was assumed to be the inevitable collapse of importance, not only because it had a the North Korean regime. -

Nationalism and the Politics of Anti-Americanism in South Korea

Volume 3 | Issue 7 | Article ID 1772 | Jul 06, 2005 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Re-writing the Past/ Re-Claiming the Future: Nationalism and the Politics of Anti-Americanism in South Korea Sheila Miyoshi Jager Re-writing the Past/ Re-Claiming the thousands of suspected leftists and political Future: Nationalism and the Politics of prisoners just before fleeing southward in July Anti-Americanism in South Korea ahead of the advancing NKPA troops. The earlier July massacre appears simply to have By Sheila Miyoshi Jager been erased from the annals of official U.S. and South Korean histories of the war. Today’s new South Korean intellectual elite, The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 coming of age during the nation’s transition to led to one of history’s worst atrocities. Known democracy in the 1990s, are actively re-writing as the Taejon massacre, an estimated 5000 to Korea’s wartime history. The Taejon massacre, 7500 civilian deaths have been attributed to a once a symbol of communist barbarity, has single incident committed by the North Korean come to mean something very different from People’s Army (NKPA) in late September 1950. past interpretations of the event. Since not one- The incident, described as “worthy of being -but two-- mass killings were committed, the recorded in the annals of history along with the September massacre is now being reconsidered Rape of Nanking, the Warsaw Ghetto, and in light of the preceding July massacre. As one other similar mass exterminations” in the journalist of the liberal Han’gyore shinmun put official United States Army report issued at the it, “the September massacre by the NKPA was end of the war, received extensive coverage in an act of retaliation for the previous killings of the international press which touted it as leftist prisoners by the Republic of Korea evidence of North Korean barbarity. -

Michael J. Allen Northwestern University Department of History 1881 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60208 [email protected]

Michael J. Allen Northwestern University Department of History 1881 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60208 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, Evanston, IL Associate Professor of 20th-century US history, 2011- Assistant Professor of 20th-century US history, 2008-11 NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY, Raleigh, NC Assistant Professor of 20th-century US history, 2003-08 EDUCATION NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, Evanston, IL Degrees: Ph.D., 2003; M.A., 1998 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Chicago, IL Degree: B.A. in History with honors, 1996 PUBLICATIONS RESEARCH MONOGRAPHS New Politics: The Imperial Presidency, The Pragmatic Left, and the Paradox of Democratic Power, 1933-1981, book manuscript in progress. Until the Last Man Comes Home: POWs, MIAs, and the Unending Vietnam War, University of North Carolina Press, 2009, paperback July 2012. RESEARCH ARTICLES "'Sacrilege of a Strange, Contemporary Kind': The Unknown Soldier and the Imagined Community After the Vietnam War," History & Memory, Vol. 23, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2011): 90-131. "'Help Us Tell the Truth About Vietnam': POW/MIA Politics and the End of the American War," in Making Sense of the Vietnam Wars: Local, National, and Transnational Perspectives, edited by Mark Philip Bradley and Marilyn B. Young, 251-75, Oxford University Press, 2008. REVIEW ARTICLES "The Pain Was Unbelievably Deep," Diplomatic History, Vol. 42, no. 2 (June 2018): 423-27 (2200 words). Allen curriculum vitae, 2020 "From Humiliation to Human Rights," Reviews in American History, Vol. 45, no. 1 (March 2017): 159- 66 (3500 words). "The Disposition of the War Dead," Encyclopedia of Military Science, Sage Publications, 2013, 1589-93 (2000 words). Review of Foreign Relations of the United States: 1969-1976, Volume VII: Vietnam, July 1970-January 1972, in Passport, Vol. -

Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: a Collection of Research Notes

235 Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: A Collection of Research Notes Rudiger Frank Abstract Starting with the public introduction of Kim Jong-un to the public in autumn of 2010 and ending with observations of consumerism in February 2017, this collection of 16 short research notes that were originally published at 38North discusses some of the most crucial issues, aside from the nuclear problem, that dominated the field of North Korean Studies in the past decade. Left in their original form, these short articles show the consistency of major North Korean policies as much as the development of our understanding of the new leader and his approach. Topics covered include the question of succession, economic statistics, new ideological trends such as pyŏngjin, techno- logical developments including a review of the North Korean tablet computer Samjiyŏn, the Korean unification issue, special economic zones, foreign trade, parliamentary elections and the first ever Party congress since 1980. Keywords: North Korea, DPRK, 38North Frank, Rudiger. “Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: A Collection of Research Notes” In Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies, Volume 9, eds. Rudiger Frank, Ina Hein, Lukas Pokorny, and Agnes Schick-Chen. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, 2017, pp. 235–350. https://doi.org/10.2478/vjeas-2017-0008 236 Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies Hu Jintao, Deng Xiaoping or another Mao Zedong? Power Restruc- turing in North Korea Date of original publication: 5 October 2010 URL: http://38north.org/2010/10/1451 “Finally,” one is tempted to say. The years of speculation and half-baked news from dubious sources are over. -

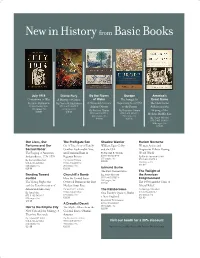

New in History from Basic Books

New in History from Basic Books July 1914 Divine Fury By the Rivers Europe America's Countdown to War A History of Genius of Water e Struggle for Great Game By Sean McMeekin By Darrin M. McMahon A Nineteenth-Century Supremacy, from 1453 e CIA’s Secret 978-0-465-03145-0 9 78-0-465-00325-9 Atlantic Odyssey to the Present Arabists and the 480 pages / hc 360 pages / hc By Erskine Clarke By Brendan Simms $29.99 $29.99 Shaping of the 978-0-465-00272-6 978-0-465-01333-3 Modern Middle East 488 pages / hc 720 pages / hc $29.99 $35.00 By Hugh Wilford 978-0-465-01965-6 384 pages / hc $29.99 Our Lives, Our The Profl igate Son Shadow Warrior Harlem Nocturne Fortunes and Our Or, A True Story of Family William Egan Colby Women Artists and Sacred Honor Con ict, Fashionable Vice, and the CIA Progressive Politics During e Forging of American and Financial Ruin in By Randall B. Woods World War II Independence, 1774-1776 Regency Britain 978-0-465-02194-9 By Farah Jasmine Griffi n 576 pages / hc By Nicola Phillips 978-0-465-01875-8 By Richard Beeman $29.99 978-0-465-02629-6 978-0-465-00892-6 264 pages / hc 528 pages / hc 360 pages / hc $26.99 $29.99 $28.99 Edmund Burke e First Conservative The Twilight of Bending Toward Churchill’s Bomb By Jesse Norman the American How the United States 978-0-465-05897-6 Justice 336 pages / hc Enlightenment e Voting Rights Act Overtook Britain in the First $27.99 e 1950s and the Crisis of and the Transformation of Nuclear Arms Race Liberal Belief American Democracy By Graham Farmelo The Rainborowes By George Marsden By Gary May 978-0-465-02195-6 One Family’s Quest to Build 978-0-465-03010-1 576 pages / hc 240 pages / hc 978-0-465-01846-8 a New England 336 pages / hc $29.99 $26.99 $28.99 By Adrian Tinniswood 978-0-465-02300-4 A Dreadful Deceit 384 pages / hc Heir to the Empire City e Myth of Race from the $28.99 New York and the Making of Colonial Era to Obama’s eodore Roosevelt America By Edward P. -

Department of History National University of Singapore Block AS 01-05-44, 11 Arts Link Singapore 117570 Email: [email protected]

September 2017 MASUDA Hajimu Department of History National University of Singapore Block AS 01-05-44, 11 Arts Link Singapore 117570 Email: [email protected] Employment 2017-2018 Wilson Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars, Washington DC, US 2012- Assistant Professor, Department of History, National University of Singapore 2001-2002 Instructor, Juniperro Serra High School, San Juan Capistrano, California, US 1998-2001 Journalist, Mainichi Shinbun [The Mainichi Newspaper], Japan Education 2012 Ph.D. Department of History, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 2008 MA Department of History, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 2005 BA Department of History, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 2003 AA Department of History, Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming 1998 BA Department of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan List of Publications: Books Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015) Reviewed by (Listed Chronologically): 1. Rana Mitter, Diplomatic History, Vol. 39 No. 5 (2015), 967-9. 2. Michael R. Dolski, Michigan War Studies Review, 2015-096 (2015). 3. Nicholas Sambaluk, H-War , H-Net Review (2015) 4. Christos G. Frentzos, Choice Review (2015) 5. John Delury, Global Asia 10:3 (2015) 6. Kazushi Minami, Not Even Past, Department of History, UT Austin (2015) 7. James Matray, New Global Studies 9:3 (2015), 351-3. 8. Allan R. Millett, Journal of Cold War Studies 17:4 (2015), 215-7. 9. Robert Hoppens, Journal of American-Eeast Asian Relations 22 (2015) 378-80 10. Kyung Deok Roh, The Journal of Northeast Asian History 12:2 (2015), 192-201 11. -

West Sea Crisis in Korea 概況報告−−朝鮮における西 海危機

Volume 8 | Issue 49 | Number 1 | Article ID 3452 | Dec 06, 2010 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Factsheet: West Sea Crisis in Korea 概況報告−−朝鮮における西 海危機 John McGlynn, Nan Kim Factsheet: WEST SEA CRISIS IN maritime dividing line between the two Koreas, KOREA which was unilaterally established by United Nations forces at the time of armistice in the Nan Kim Korean War in 1953, and has been contested by the North ever since, hugs its western Introduction coastline. John McGlynn Echoing the views of Siegried Hecker, who recently toured North Korea's nuclear facilities The factsheet that follows, prepared by Nan (see "Stanford University Professor's Report on Kim in conjunction with members of the the Implications of North Korea's Uranium National Campaign to End the Korean War, Enrichment Program" at our website's What's provides an informative overview of theHot for the week of November 21,link ), and dangerous military standoff that has been others who advocate peaceful diplomacy to end unfolding on the Korean Peninsula ever since the (potentially nuclear) armed standoff on the South Korea conducted a 4-hour artillery Korean Peninsula in the short run, a prelude to exercise on November 23. The exercise was achieving a permanent peace in Northeast Asia conducted on Yeonpyeong Island, populated at in the long-run, the Campaign's factsheet the time by 1,000 South Korean soldiers and makes this statement: 1,300 civilians, about 12 kilometers from North Korea's coastline. The North -- which had "Direct negotiations, as a first step toward a demanded that the South cancel the exercise peace treaty or agreement [with the U.S. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/88w5d6zj Author Stock, Thomas Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Thomas Stock 2018 © Copyright by Thomas Stock 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION From Soviet Origins to Chuch’e: Marxism-Leninism in the History of North Korean Ideology, 1945-1989 by Thomas Stock Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Namhee Lee, Chair Where lie the origins of North Korean ideology? When, why, and to what extent did North Korea eventually pursue a path of ideological independence from Soviet Marxism- Leninism? Scholars typically answer these interrelated questions by referencing Korea’s historical legacies, such as Chosŏn period Confucianism, colonial subjugation, and Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla experience. The result is a rather localized understanding of North Korean ideology and its development, according to which North Korean ideology was rooted in native soil and, on the basis of this indigenousness, inevitably developed in contradistinction to Marxism-Leninism. Drawing on Eastern European archival materials and North Korean theoretical journals, the present study challenges our conventional views about North Korean ideology. -

The United States Information Agency in South Vietnam, 1954-1960

Selling America, Ignoring Vietnam: The United States Information Agency in South Vietnam, 1954-1960 by Brendan D‟Arcy Wright A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARITIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2009 © Brendan D‟Arcy Wright, 2009 Abstract Once a neglected institution, the United States Information Agency (USIA) has recently received attention from scholars who wish to study American public relations, propaganda, and cultural diplomacy during the Cold War. Here, I present a case study of the USIA‟s activities in South Vietnam in 1954-1960 as a way to further investigate these issues. This thesis explores both the overt and covert aspects of the USIA‟s operations within Vietnam, and attempts to gauge the Agency‟s effectiveness. My study contends that forces internal to early American Cold War culture—racism and class—set the parameters of the USIA‟s mission, defined the nature of its propaganda, and ultimately contributed to its ineffectiveness. Saddled to their own set of racist and self-referential belief systems, USIA officials remained remarkably ignorant of Vietnamese culture to the detriment of their mission‟s success. As such, the central goals of the USIA‟s mission—to inculcate the Vietnamese with American liberal democratic values, to market the Diem regime as the legitimate manifestation of these principles, and to taint Ho Chi Minh‟s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DVN) as a puppet state of the Soviet Union—never took hold. Following the pioneering work of Kenneth Osgood, this study also sheds light on the USIA‟s preference for “gray” propaganda: USIA-produced propaganda which appeared to emit from an independent or indigenous source. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

Kim Il Sung Reminiscences with the Century Vol. V

Kim Il Sung Reminiscences With the Century Vol. V A Aan-ri, (V) 438 Advance Association, (V) 255 Africa, (V) 272 Amnok River, (V) 52, 83, 84, 88, 92, 131, 135, 144, 151, 163, 185, 190, 196, 197, 202, 210, 259, 260, 310, 311, 312, 314, 315, 319, 323, 336, 438, 441, 447 Riverine Road, (V) 102 Amur River, (V) 72, 445 An Chang Ho, (V) 252 An Chung Gun, (V) 349, 366 An Jong Suk, (V) 216, 216 An Kwang Chon, (V) 249, 252 An Tok Hun, (V) 191, 320, 321, 322 An Yong Ae, (V) 79 Anti-Communism, (V) 105, 272, 355 Anti-Factionalism (poem), (V) 237 Anti-Feudalism, (V) 375, 380 Anti-Imperialist Youth League, (V) 221, 267, 430 Anti-Japanese, (V) 3, 3, 7, 8, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 47, 51, 52, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 64, 65, 70, 75, 79, 82, 83,85, 92, 96, 103, 105, 108, 111, 114, 115, 122, 124, 126, 132, 133, 134, 135, 137, 139, 140, 142, 143, 144, 147, 148, 156, 157, 163, 165, 170, 174, 181, 182, 183, 185, 186, 187, 192, 193, 200, 204, 205, 207, 208, 221, 227, 231, 232, 233, 234, 239, 240, 241, 245, 250, 251, 255, 261, 263, 264, 265, 270, 271, 275, 279, 281, 282, 285, 294, 295, 298, 301, 304, 305, 309, 310, 312, 313, 322, 328, 334, 346, 348, 349, 350, 351, 353, 363, 377, 382, 384, 387, 388, 390, 392, 396, 405, 407, 421, 436, 445 Allied Army, (V) 202, 263 Association, (V) 26, 30, 209, 255, 305 Guerrilla Army of Northern Korea, (V) 306, 307 Youth Daily, (V) 228 Youth League, (V) 189, 244, 434 Anti-Manchukuo, (V) 148, 315 Anti-Soviet, (V) 274 Antu, (V) 4, 42, 47, 48, 76, 133, 138, 210, 216, 216, 325 Appeal