Vanderbilt University 4829948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Ted Geltner Journal of Magazine Media, Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2012, (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jmm.2012.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/773721/summary [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 07:15 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Literary War Journalism Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Jacksonville University [email protected] Ted Geltner, Valdosta State University [email protected] Abstract Relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the ways literary journalists construct meaning within their narratives. This article employed rhetorical framing analysis to discover embedded meaning within the text of John Sack’s Gulf War Esquire articles. Analysis revealed several dominant frames that in turn helped construct an overarching master narrative—the “takeaway,” to use a journalistic term. The study concludes that Sack’s literary approach to war reportage helped create meaning for readers and acted as a valuable supplement to conventional coverage of the war. Keywords: Desert Storm, Esquire, framing, John Sack, literary journalism, war reporting Introduction Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war. —Carl von Clausewitz Long before such present-day literary journalists as Rolling Stone’s Evan Wright penned Generation Kill (2004) and Chris Ayres of the London Times gave us 2005’s War Reporting for Cowards—their poignant, gritty, and sometimes hilarious tales of embedded life with U.S. -

On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis

Socialism and Democracy ISSN: 0885-4300 (Print) 1745-2635 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csad20 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell To cite this article: Thomas Powell (2018) On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis, Socialism and Democracy, 32:1, 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 Published online: 17 Apr 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 200 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=csad20 Socialism and Democracy, 2018 Vol. 32, No. 1, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell I Milton Leitenberg’s biological warfare (BW) hoax theory is not believable. For the past three decades, Leitenberg has paraded the thesis that the allegations of BW use leveled against the US by North Korea and China during the Korean War has all been a nefarious hoax – a grand piece of political theater – deviously orchestrated by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and the swarthy Joseph Stalin. Leitenberg’s thesis epitomizes the deeply embedded racism of America’s Cold War politics. He has enjoyed bounteous support from right-wing academia and quasi-government think tanks. The BW hoax thesis has impacted scholarship and US foreign policy, and it is a major stumbling block to improving US relations with North Korea. In this article I will argue that Leitenberg’s thesis is a house of cards built on forged docu- ments, false claims and fake facts. -

Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-Related Publications

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Finding Aids Special Collections Department 1-31-2020 Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-related publications Carolina Mercado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/finding_aid This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guide to MS 677 Vietnam War-related publications 1962 – 2010s Span Dates, 1966 – 1980s Bulk Dates 3 feet (linear) Inventory by Carolina Mercado July 30, 2019; January 31, 2020 Donated by Howard McCord and Dennis Bixler-Marquez. Citation: Vietnam War-related publications, MS677, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department. The University of Texas at El Paso Library. C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department University of Texas at El Paso Historical Sketch The Vietnam War (1954 – 1975) was a military conflict between the communist North Vietnamese (Viet Cong) and its allies and the government of South Vietnam and its allies (mainly the United States). The North Vietnamese sought to unify Vietnam under a communist regime, while South Vietnam wanted to retain its government, which was aligned with the West. The war was also a result of the ongoing Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. On July 2, 1976 the North Vietnamese united the country after the South Vietnamese government surrendered on April 30. Millions of soldiers and civilians were killed during the Vietnam War. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, “The Vietnam War,” accessed on January 31, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War] Series Description or Arrangement This collection was left in the order found by the archivist. -

LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A

LiteraryStudies Journalism Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 Return address: Literary Journalism Studies State University of New York at Cortland Department of Communication Studies P.O. Box 2000 LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A. Literary Journalism Studies Inaugural Issue The Problem and the Promise of Literary Journalism Studies by Norman Sims An exclusive excerpt from the soon-to-be-released narrative nonfiction account, published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath by Michael and Elizabeth Norman Writing Narrative Portraiture by Michael Norman South: Where Travel Meets Literary Journalism by Isabel Soares Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 2009 Spring 1, No. 1, Vol. “My Story Is Always Escaping into Oher People” by Robert Alexander Differently Drawn Boundaries of the Permissible by Beate Josephi and Christine Müller Recovering the Peculiar Life and Times of Tom Hedley and of Canadian New Journalism by Bill Reynolds Published at the Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University 1845 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, U.S.A. The Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies On the Cover he ghost image in the background of our cover is based on this iconic photo Tof American prisoners-of-war, hands bound behind their backs, who took part in the 1942 Bataan Death March. The Death March is the subject of Michael and Elizabeth M. Norman’s forthcoming Tears in the Darkness, pub- lished by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Excerpts begin on page 33, followed by an essay by Michael Norman on the challenges of writing the book, which required ten years of research, travel, and interviewing American and Filipino surivivors of the march, as well as Japanese participants. -

Xikang: Han Chinese in Sichuan's Western Frontier

XIKANG: HAN CHINESE IN SICHUAN’S WESTERN FRONTIER, 1905-1949. by Joe Lawson A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Abstract This thesis is about Han Chinese engagement with the ethnically diverse highlands west and south-west of the Sichuan basin in the first half of the twentieth century. This territory, which includes much of the Tibetan Kham region as well as the mostly Yi- and Han-settled Liangshan, constituted Xikang province between 1939 and 1955. The thesis begins with an analysis of the settlement policy of the late Qing governor Zhao Erfeng, as well as the key sources of influence on it. Han authority suffered setbacks in the late 1910s, but recovered from the mid-1920s under the leadership of General Liu Wenhui, and the thesis highlights areas of similarity and difference between the Zhao and Liu periods. Although contemporaries and later historians have often dismissed the attempts to build Han Chinese- dominated local governments in the highlands as failures, this endeavour was relatively successful in a limited number of places. Such success, however, did not entail the incorporation of territory into an undifferentiated Chinese whole. Throughout the highlands, pre-twentieth century local institutions, such as the wula corvée labour tax in Kham, continued to exercise a powerful influence on the development and nature of local and regional government. The thesis also considers the long-term life (and death) of ideas regarding social transformation as developed by leaders and historians of the highlands. -

Koje Unscreened

KOJE UNSCREENED by WILFRED BURCHETT and ALAN WINNINGTON Cover Illustration KOREAN AND CHINESE PRISONERS SEARCHED In compound 76 in June 1952, U.S. paratroopers rounded up prisoners in a bloody battle. They are now being stripped and searched while buildings still burn in the background. Their personal effects, including home-made gas masks, cover the ground. 31 prisoners were killed and over 80 wounded. 2 PRISONERS BURNED OUT IN COMPOUND 76 Dense smoke rises as U.S. Paratroopers move in on June 10, 1952 to force prisoners into small groups. Scores of prisoners were wounded and 31 killed 3 ON KOJE Bodies of wounded or dead prisoners in compound 76 lie in the wreckage. Others, some wounded, move towards the compound gate. In pitched battles following an order from Brig.- Gen. Boatner for prisoners to be moved to another compound, 31 were killed. 4 Compound 76 early May 1952. June 10th U.S. troops hurled tear gas bombs to force prisoners to newly-built stockades. At least 25 killed. 5 WHILE BRITISH PRISONERS Get suntanned on the hillside. Keith Clarke and Cecil McKee 6 Check mate with a laugh. Fred Moore wins the game from George Hobson, while another British prisoner, Sid Carr, looks on 7 Prisoners in Compound 96 hold a memorial service for five killed by guards. The casket is surrounded by paper flower wreaths. 8 Tear gas raid on compound 96 as troops move in to tear down flags. Soldiers and a heavy tank stand by. 9 British prisoners cheer their team on in the game 10 British prisoners give P.T. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

Bruce Cumings, the Korean

THE KOREAN WAR clan A9:4 A HISTORY ( toot ie let .•-,• ••% ale draa. • 0%1. • .„ \ •r• • • di 11111 1 41'• di• wrsn..."7 • -s. ve,„411p- • dm0 41N-Nitio6 u". •••• -- 411 • ose - r 011.,r•rw••••••• ate,tit 0it it& ado tem.........,111111111nrra° 1 40 Of ••••••—•S‘ 11••••••••••••••• 4,1••••••• o CUMINGS' •IP • AABOUTBOUT THE AAUTHORUTHOR BRUCE CCUMINGSUMINGS is the Gustavus F. and Ann M.M. Swift DistinguishedDistinguished Service ProfessorProfessor inin HistoryHistory atat the University ofof ChicagoChicago and specializesspecializes inin modernmodem KoreanKorean history,history, internationalinternational history,history, andand EastEast AsianAsian–American–American relations. 2010 Modern LibraryLibrary EditionEdition CopyrightCopyright CD© 2010 by Bruce Cumings Maps copyrightcopyright ©0 2010 by Mapping Specialists AllAll rights reserved. Published in the United States by Modern Library,Library, an imprintimprint ofof TheThe Random HouseHouse PublishingPublishing Group,Group, a division ofof RandomRandom House, Inc., New York.York. MODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER DesignDesign areare registeredregistered trademarkstrademarks ofof RandomRandom House,House, Inc.Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGINGCATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION-IN-PUBLICATION DATADATA Cumings,Cumings, Bruce TheThe KoreanKorean War/BruceWar/Bruce Cumings. p. cm.cm.—(A—(A modern librarylibrary chronicleschronicles book)book) eISBN:eISBN: 978-0-679-60378-8978-0-679-60378-8 1.1. Korean War, 1950-1953.1950–1953. 22. KoreanKorean War, 19501950-1953—United–1953—United States. 3. Korean War,War, 19501950-1953—Social–1953—Social aspectsaspects—United—United States. I. Title. DS918.C75D5918.C75 2010 951 951.904 .9042—dc22′2—dc22 2010005629 2010005629 www.modernlibrary.comwww.modemlibrary.com v3.0 CHRONOLOGY 2333 B.C.B.C. Mythical Mythical founding ofof thethe Korean nationnation byby Tangun and hishis bear wifewife. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels Among Head- Hunters and Slave-Owners in South-West China by Alan Winnington Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw.Cited by: 4Author: Alan Winnington5/5(2)Publish Year: 1959The Slaves of the Cool Mountains by Alan Winnington (2008 ...https://www.ebay.com/p/69739877Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw. From that journey was born The Slaves of the Cool Mountains, which Neal Ascherson has called 'one of the classics of modern … Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu … Nov 11, 2016 · Best Buy Deals The Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels Among Head-Hunters and Slave-Owners in Alan Winnington traveled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the headhunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw. The first European to enter and leave this area alive, Winnington reported on the struggle of recently released slaves as they came to terms with their newfound freedom.4.4/5(5)Format: PaperbackPrice Range: £7.25 - £18.98Alan Winnington - Wikipediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_WinningtonOverviewStudy of Chinese slavery and headhuntingEarly careerKorean War – "I Saw Truth in Korea"Life in GermanyWorksExternal linksIn 1954 Winnington's passport expired and was not renewed by the British government authorities making him virtually stateless (though it was eventually renewed in 1968). -

Neasialookinside.Pdf

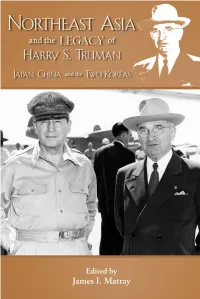

The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in Northeast Asia The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 8 Based on the Eighth Truman Legacy Symposium The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas May 2010 Key West, Florida Edited by James I. Matray Copyright © 2012 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman and General MacArthur at Wake Island, October 15, 1950 (HSTL 67-434). Cover design: Katie Best Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Truman Legacy Symposium (8th : 2010 : Key West, Fla.) Northeast Asia and the legacy of Harry S. Truman : Japan, China, and the two Koreas / edited by James I. Matray. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; volume 8) “Based on the eighth Truman Legacy Symposium, The legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the two Koreas, May, 2010, Key West, Florida.” Includes index. 1. East Asia—Relations—United States—Congresses. 2. United States—Relations— East Asia—Congresses. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1945–1953—Congresses. 4. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Congresses. I. Matray, James Irving, 1948–, editor of compilation. II. Title. DS518.8.T69 2010 327.507309'044—dc23 2012011870 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48– 1992. To Amanda Jane Matray A Master Teacher Contents Illustrations .........................................ix Preface ..............................................xi General Editor’s Preface .............................xiii Introduction .........................................1 Mild about Harry— President Harry S.