Koje Unscreened

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

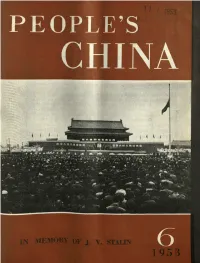

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis

Socialism and Democracy ISSN: 0885-4300 (Print) 1745-2635 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csad20 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell To cite this article: Thomas Powell (2018) On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis, Socialism and Democracy, 32:1, 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 Published online: 17 Apr 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 200 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=csad20 Socialism and Democracy, 2018 Vol. 32, No. 1, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell I Milton Leitenberg’s biological warfare (BW) hoax theory is not believable. For the past three decades, Leitenberg has paraded the thesis that the allegations of BW use leveled against the US by North Korea and China during the Korean War has all been a nefarious hoax – a grand piece of political theater – deviously orchestrated by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and the swarthy Joseph Stalin. Leitenberg’s thesis epitomizes the deeply embedded racism of America’s Cold War politics. He has enjoyed bounteous support from right-wing academia and quasi-government think tanks. The BW hoax thesis has impacted scholarship and US foreign policy, and it is a major stumbling block to improving US relations with North Korea. In this article I will argue that Leitenberg’s thesis is a house of cards built on forged docu- ments, false claims and fake facts. -

Xikang: Han Chinese in Sichuan's Western Frontier

XIKANG: HAN CHINESE IN SICHUAN’S WESTERN FRONTIER, 1905-1949. by Joe Lawson A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Victoria University of Wellington 2011 Abstract This thesis is about Han Chinese engagement with the ethnically diverse highlands west and south-west of the Sichuan basin in the first half of the twentieth century. This territory, which includes much of the Tibetan Kham region as well as the mostly Yi- and Han-settled Liangshan, constituted Xikang province between 1939 and 1955. The thesis begins with an analysis of the settlement policy of the late Qing governor Zhao Erfeng, as well as the key sources of influence on it. Han authority suffered setbacks in the late 1910s, but recovered from the mid-1920s under the leadership of General Liu Wenhui, and the thesis highlights areas of similarity and difference between the Zhao and Liu periods. Although contemporaries and later historians have often dismissed the attempts to build Han Chinese- dominated local governments in the highlands as failures, this endeavour was relatively successful in a limited number of places. Such success, however, did not entail the incorporation of territory into an undifferentiated Chinese whole. Throughout the highlands, pre-twentieth century local institutions, such as the wula corvée labour tax in Kham, continued to exercise a powerful influence on the development and nature of local and regional government. The thesis also considers the long-term life (and death) of ideas regarding social transformation as developed by leaders and historians of the highlands. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels Among Head- Hunters and Slave-Owners in South-West China by Alan Winnington Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw.Cited by: 4Author: Alan Winnington5/5(2)Publish Year: 1959The Slaves of the Cool Mountains by Alan Winnington (2008 ...https://www.ebay.com/p/69739877Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw. From that journey was born The Slaves of the Cool Mountains, which Neal Ascherson has called 'one of the classics of modern … Beijing, 1956: foreign correspondent Alan Winnington heard reports of slaves being freed in the mountains of south-west China. The following year he travelled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the head-hunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu … Nov 11, 2016 · Best Buy Deals The Slaves of the Cool Mountains: Travels Among Head-Hunters and Slave-Owners in Alan Winnington traveled to Yunnan province and spent several months with the headhunting Wa and the slave-owning Norsu and Jingpaw. The first European to enter and leave this area alive, Winnington reported on the struggle of recently released slaves as they came to terms with their newfound freedom.4.4/5(5)Format: PaperbackPrice Range: £7.25 - £18.98Alan Winnington - Wikipediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_WinningtonOverviewStudy of Chinese slavery and headhuntingEarly careerKorean War – "I Saw Truth in Korea"Life in GermanyWorksExternal linksIn 1954 Winnington's passport expired and was not renewed by the British government authorities making him virtually stateless (though it was eventually renewed in 1968). -

4. the Democracy Wall

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Minkan in China: 1949–89 SHAO Jiang School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2011. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] MINKAN IN CHINA: 1949–89 SHAO Jiang PhD 2011 MINKAN IN CHINA: 1949–89 SHAO Jiang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westmister for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 Abstract This paper presents the first panoramic study of minkan (citizen publications) in China from the 1950s until the 1980s. The purpose of doing so is to recover the thoughts and practice obliterated by state power by examining unofficial magazines as having social, political and historical functions. Moreover, it attempts to examine this recent history against the backdrop of the much older history of Chinese print culture and its renaissance. -

Burchett's Korean

Steven Casey Wilfred Burchett and the UN command's media relations during the Korean War, 1951-52 Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Casey, Steven (2010) Wilfred Burchett and the UN command's media relations during the Korean War, 1951-52. Journal of military history, 74 . ISSN 0899-3718 © 2010 Society for Military History This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27772/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2010 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. 1 WILFRED BURCHETT & THE UN COMMAND’S MEDIA RELATIONS DURING THE KOREAN WAR, 1951-1952 Few Cold War correspondents were more controversial than Wilfred Burchett. To the left he was a radical truth-hunter, roving around Asia and uncovering the big stories largely because he was unencumbered by the corporate, ideological, and governmental constraints that made so many Western reporters silent about the errors, even crimes, of their own side. -

The CIA's Anti-China Crusade

TIBET and the CIA’s anti-China crusade New Edition Articles from Workers World, including Sam Marcy’s 1959 “Class War in Tibet.” Updated to included reports from 2008. $5 WW PUBLISHERS 55 W. 17 th St., 5th Fl, NY, NY 10011 212-627-2994 TIBET SECTION 1 Anti-China protest made in USA, not Tibet 1 Gary Wilson April 24, 2008 Cultural genocide: In Tibet or New Orleans? 2 Larry Hales April 10, 2008 Nepal’s revolutionaries stand with China 3 David Hoskins April 10, 2008 Cuba, Venezuela gov’ts denounce China bashing 4 April 10, 2008 Behind the anti-China Olympics campaign 5 Gary Wilson April 3, 2008 Tibet and the March 10 commemoration of the CIA’s 1959 ‘uprising’ 6 Gary Wilson March 27, 2008 MUNDO OBRERO Tíbet y la conmemoración del ‘levantamiento’ de la CIA del 19 de marzo de 1959. 7 Gary WIlson 27 de Marzo SECTION 2 Bush greets the Dalai Lama Behind U.S. support for Tibetan feudalists 10 Deirdre Griswold June 2001 What’s CIA up to with the Dalai Lama? 12 Sara Flounders August 26, 1999 It was no Shangri-la: Hollywood hides Tibet’s true history 14 Gary Wilson December 4, 1997 That’s entertainment? It’s propaganda Tibet as it never was 18 Gary Wilson October 23, 1997 CIA ran Tibet contras since 1950s 22 Gary Wilson February 6, 1997 The Dalai Lama & the CIA 23 Editorial Class War in Tibet 24 Sam Marcy April 1059, Note: This booklet has been updated. A new Section Two has been added with articles written in 2008. -

The Shanghai News (1950-1952) : External Propaganda and New Democracy in Early 1950S Shanghai

This is a repository copy of The Shanghai News (1950-1952) : external propaganda and New Democracy in early 1950s Shanghai. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/155879/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Howlett, Jonathan James orcid.org/0000-0002-1373-0737 (2021) The Shanghai News (1950-1952) : external propaganda and New Democracy in early 1950s Shanghai. Journal of Chinese History. pp. 107-130. ISSN 2059-1632 https://doi.org/10.1017/jch.2020.5 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Jonathan J. Howlett The Shanghai News (1950-1952): New Democracy and external propaganda in early 1950s Shanghai Short title: The Shanghai News (1950-1952) and New Democracy NOTE: This article has been accepted for publication in a revised form in the January 2021 edition of the Journal of Chinese History, published by Cambridge University Press. Abstract: The Shanghai News was the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) first English-language newspaper. -

Italy's Communist Party and People's China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università degli Studi di... ROADS TOROADS RECONCILIATION e-ISSN 2610-9042 Sinica venetiana 5 ISSN 2610-9654 — Roads to Reconciliation People’s Republic of China, Western Europe and Italy GRAZIANI MENEGUZZI, SAMARANI, During the Cold War Period (1949-1971) edited by Guido Samarani Carla Meneguzzi Rostagni Sofia Graziani Edizioni Ca’Foscari Roads to Reconciliation Sinica venetiana Collana diretta da Tiziana Lippiello e Chen Xiaoming 5 Edizioni Ca’Foscari Sinica venetiana Direzione scientifica | Scientific editors Tiziana Lippiello (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Chen Yuehong (Peking University, China) Comitato scientifico | Scientific committee Chen Hongmin (Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China) Sean Golden (UAB Barcelona, España) Roger Greatrex (Lun- ds Universitet, Sverige) Jin Yongbing (Peking University, China) Olga Lomova (Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Cˇeská Republika) Burchard Mansvelt Beck (Universiteit Leiden, Nederland) Michael Puett (Harvard University, Cambridge, USA) Mario Sabattini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Tan Tian Yuan (SOAS, London, UK) Hans van Ess (LMU, München, Deutschland) Giuseppe Vignato (Peking University, China) Wang Keping (CASS, Beijing, China) Yamada Tatsuo (Keio University, Tokyo, Japan) Yang Zhu (Peking University, China) Comitato editoriale | Editorial board Magda Abbiati (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Attilio Andreini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, -

Vanderbilt University 4829948

PRISONERS, DIPLOMATS, AND SABOTEURS: AN INTERNATIONAL HISTORY OF THE DIPLOMACY OF CAPTIVITY DURING AND FOLLOWING THE KOREAN WAR By Lu Sun Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2017 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Thomas A. Schwartz, Ph.D. Paul A. Kramer, Ph.D. Ruth Rogaski, Ph.D. Brett V. Benson, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. iii Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... iv Chapter Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ....................................................................................................................... 3 Approaches and Significance of the Study ........................................................................... 7 II. “Segregating” by Race, Rank, and Nationality: China’s Failed Ideological Indoctrination During the Korean War .................................................................................... 12 Atrocity Charges and Leniency Policy ............................................................................... 18 Battle for Ideological Supremacy ....................................................................................... -

Anti-Communism and the Korean War (1950-195 3)

ANTI-COMMUNISM AND THE KOREAN WAR (1950-195 3) Jon Halliday I. Zntroduction On April 16, 1952 the (London) Daily Worker carried a small item about a press conference given in Mexico City by the great Mexican painter, Diego Rivera. His latest painting, Nightmare of War and Dream of Peace, commissioned by the government, had just been cut down. Its two themes were the collection of signatures (includidg by Frida Kahlo) for the Five- Power Peace Pact and the exposure of the atrocities of the Korean War. The painting has since disappeared (it is reportedly in Beijing). Even Picasso's Massacre in Korea (195 1) is rarely reproduced or mentioned. Rather, the Korean War is 'known', indeed un-known, to much of the Western world through M.A.S.H. This brilliantly resolves the problem of the nature of the Korean War by keeping almost all Koreans well out of sight, and isolating a few GIs in a tent, leaving them to ruminate about sickness, sex and golf. In its evasion, M.A.S.H. reveals a central truth about the Korean War- that it was not just anti-Communist but so anti-Korean that the US and its allies, including Britain, not only could not take in who the enemy really was, but even who their Korean allies were. All Koreans became 'gooks' and very soon US pilots were being given orders to strafe, napalm and bomb any grouping of ~oreans.' In Western history and mythology there has been a double elimination: of Korean Communism and of the Korean revolutionary movement, on the one hand, and of the whole history, culture and society of Korea as a nation.