Sources, History, Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

Mon-Khmer Studies VOLUME 42 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures Established 1964 Copyright for these papers vested in the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 42 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published in 2013 by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Papers (Peer reviewed) K. S. NAGARAJA, Paul SIDWELL, Simon GREENHILL A Lexicostatistical Study of the Khasian Languages: Khasi, Pnar, Lyngngam, and War 1-11 Michelle MILLER A Description of Kmhmu’ Lao Script-Based Orthography 12-25 Elizabeth HALL A phonological description of Muak Sa-aak 26-39 YANIN Sawanakunanon Segment timing in certain Austroasiatic languages: implications for typological classification 40-53 Narinthorn Sombatnan BEHR A comparison between the vowel systems and the acoustic characteristics of vowels in Thai Mon and BurmeseMon: a tendency towards different language types 54-80 P. K. CHOUDHARY Tense, Aspect and Modals in Ho 81-88 NGUYỄN Anh-Thư T. and John C. L. INGRAM Perception of prominence patterns in Vietnamese disyllabic words 89-101 Peter NORQUEST A revised inventory of Proto Austronesian consonants: Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic Evidence 102-126 Charles Thomas TEBOW II and Sigrid LEW A phonological description of Western Bru, Sakon Nakhorn variety, Thailand 127-139 Notes, Reviews, Data-Papers Jonathan SCHMUTZ The Ta’oi Language and People i-xiii Darren C. GORDON A selective Palaungic linguistic bibliography xiv-xxxiii Nathaniel CHEESEMAN, Jennifer -

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

DAI Hongwu, Assistant Professor of Foreign Languages (On Leave), Yunnan Normal University; Ph.D

Designing effective learning experiences for diverse and scattered ethnic minority groups across Yunnan Province, China DAI Hongwu, Assistant Professor of Foreign Languages (on leave), Yunnan Normal University; Ph.D. student, organizational leadership, Eastern University, [email protected] Dennis Cheek, Chief Learning Officer, Values Education Pte. Ltd., Singapore, [email protected]; Visiting Professor, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, IÉSEG School of Management, France, [email protected]; Consulting Professor, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam, [email protected] Abstract Five key interrelated areas are being mapped, analyzed, and synthesized to better understand the challenges and issues for quality multicultural educational materials and learning experiences for ethnic minority groups within a large province in southwest China. Rapid urbanization and intensive social exchanges have changed the cultural outlook of ethnic minority groups and society. The related educational issue is how to preserve the cultures and languages of ethnic minorities and their sociocultural identity in the process of government-encouraged social and cultural integration with Han culture, Mandarin, and modernity. Sociocultural Ethnic Minority Groups in Yunnan Province, PRC Yunnan Province in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is slightly smaller in size than the U.S. state of California. Its diverse geography and widespread rurality are home to approximately 48.3 million people (2018 estimate). While the majority are of Han ethnicity, 34% (16.4 million) of the population are members of ethnic minority groups. The 25 largest ethnic groups within the province have populations of 5,000 or more, including the Yi, Hani, Bai, Dai, Zhuang, Miao, Hui, and Lahu. A number of these ethnic groups also move freely back and forth between the borders of the PRC and neighboring countries leading to fluctuations in minority populations and quite active cross-border relations. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis

Socialism and Democracy ISSN: 0885-4300 (Print) 1745-2635 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csad20 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell To cite this article: Thomas Powell (2018) On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis, Socialism and Democracy, 32:1, 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 Published online: 17 Apr 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 200 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=csad20 Socialism and Democracy, 2018 Vol. 32, No. 1, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell I Milton Leitenberg’s biological warfare (BW) hoax theory is not believable. For the past three decades, Leitenberg has paraded the thesis that the allegations of BW use leveled against the US by North Korea and China during the Korean War has all been a nefarious hoax – a grand piece of political theater – deviously orchestrated by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and the swarthy Joseph Stalin. Leitenberg’s thesis epitomizes the deeply embedded racism of America’s Cold War politics. He has enjoyed bounteous support from right-wing academia and quasi-government think tanks. The BW hoax thesis has impacted scholarship and US foreign policy, and it is a major stumbling block to improving US relations with North Korea. In this article I will argue that Leitenberg’s thesis is a house of cards built on forged docu- ments, false claims and fake facts. -

ITRI High-Level Assessment on OECD Annex II Risks in Wa Territory In

| High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 ITRI High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar May 2015 v1.0 | High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 Synergy Global Consulting Ltd United Kingdom office: South Africa office: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1865 558811 Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 3077 www.synergy-global.net 1a Walton Crescent, Forum II, 4th Floor, Braampark Registered in England and Wales 3755559 Oxford OX1 2JG 33 Hoofd Street Registered in South Africa 2008/017622/07 United Kingdom Braamfontein, 2001, Johannesburg, South Africa Client: ITRI Ltd Report Title: High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar Version: Version 1.0 Date Issued: 11 May 2015 Prepared by: Quentin Sirven Benjamin Nénot Approved by: Ed O’Keefe Front Cover: Panorama of Tachileik, Shan State, Myanmar. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ITRI Ltd. The report should be reproduced only in full, with no part taken out of context without prior permission. The authors believe the information provided is accurate and reliable, but it is furnished without warranty of any kind. ITRI gives no condition, warranty or representation, express or implied, as to the conclusions and recommendations contained in the report, and potential users shall be responsible for determining the suitability of the information to their own circumstances. -

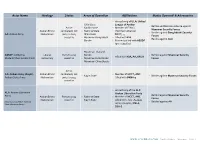

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau UNESCO PUBLISHING MEMORY OF PEOPLES 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 1 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 3 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by YVES GOUDINEAU Memory of Peoples | UNESCO Publishing 34_Laos_GB_INT 7/07/03 11:12 Page 4 The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNESCO wishes to express its gratitude to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for its support to this publication through the UNESCO/Japan Funds-in-Trust for the Safeguarding and Promotion of Intangible Heritage. Published in 2003 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy F-75352 Paris 07 SP Plate section: Marion Dejean Cartography and drawings: Marina Taurus Composed by La Mise en page Printed by Imprimerie Leclerc, Abbeville, France ISBN 92-3-103891-5 © UNESCO 2003 Printed in France 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 5 5 Foreword YVES GOUDINEAU It is quite clear to every observer that Laos owes part of its cultural wealth to the unique diversity which resides in the bosom of the different populations that have settled on its present territory down the ages, bringing with them a mix of languages, beliefs and aesthetic traditions. -

Myanmar's 2020 Election: the COMPETING INTERESTS of CHINA and INDIA

Myanmar's 2020 Election: THE COMPETING INTERESTS OF CHINA AND INDIA By Yan Myo Thein |Independent Analyst| October 2020 About the Report This report evaluates the competing interests of China and India in Myanmar’s 2020 General Election based on the current and historical documents, media reportages and online interviews, relevant to the multiparty general elections in Myanmar (Burma). The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) provided financial support to the research. About the Author Yan Myo Thein, a former political prisoner, is a political commentator cum analyst as well as an independent researcher, based in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar (Burma), who has covered Myanmar (Burma)’s making of a democratic federal union, peacebuilding and foreign relations, especially its ties with China and India for more than twenty years. He now writes for the local daily newspapers, the Daily Eleven and the 7th Day Daily in Myanmar and makes the political insights on Myanmar (Burma) for the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), VOA, RFA and BBC. 1 Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Myanmar Election and China ...................................................................................................................... 6 Overview of History ............................................................................................................................... -

Ethnic Politics and the 2015 Elections in Myanmar

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 16 | September 2015 Ethnic Politics and the 2015 Elections in Myanmar KEY POINTS • The 2015 general election presents an important opportunity to give political voice to Myanmar’s diverse ethnic nationality communities and empower them to pursue their aspirations, provided that it is genuinely free and fair. • If successfully held, the general election is likely to mark another key step in the process of national transition from decades of military rule. However the achievement of nationwide peace and further constitutional reform are still needed to guarantee the democratic rights, representation and participation of all peoples in determining the country’s future. • Although nationality parties are likely to win many seats in the polls, the impact of identity politics and vote-splitting along ethnic and party lines may see electoral success falling short of expectations. This can be addressed through political cooperation and reform. It is essential for peace and stability that the democratic process offers real hope to nationality communities that they can have greater control over their destiny. • Inequitable distribution of political and economic rights has long driven mistrust and conflict in Myanmar. The 2015 general election must mark a new era of political inclusion, not division, in national politics. After the elections, it is vital that an inclusive political dialogue moves forward at the national level to unite parliamentary processes and ethnic ceasefire talks as a political roadmap for all citizens. ideas into movement Introduction Myanmar/Burma1 is heading to the polls in November 2015, in what will be a closely watched election. Provided that they are free and fair, the polls are likely to have a major influence over the future political direction of the country, with an expected shift in power from the old elite to the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD).