Foreigners Under Mao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

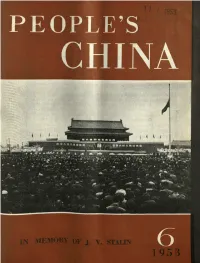

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

H-Diplo Article Roundtable Review, Vol. X, No. 24

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Article Roundtable Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Review Introduction by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Reviewers: Bruce Craig, Ronald Radosh, Katherine A.S. Volume X, No. 24 (2009) Sibley, G. Edward White 17 July 2009 Response by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr Journal of Cold War Studies 11.3 (Summer 2009) Special Issue: Soviet Espoinage in the United States during the Stalin Era (with articles by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr; Eduard Mark; Gregg Herken; Steven T. Usdin; Max Holland; and John F. Fox, Jr.) http://www.mitpressjournals.org/toc/jcws/11/3 Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-24.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by Bruce Craig, University of Prince Edward Island ..................................................... 8 Review by Ronald Radosh, Emeritus, City University of New York ........................................ 16 Review by Katherine A.S. Sibley, St. Josephs University ......................................................... 18 Review by G. Edward White, University of Virginia School of Law ........................................ 23 Author’s Response by John Earl Haynes, Library of Congress, and Harvey Klehr, Emory University ................................................................................................................................ 27 Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. -

Biographyelizabethbentley.Pdf

Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 1 of 284 QUEEN RED SPY Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 2 of 284 3 of 284 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet RED SPY QUEEN A Biography of ELIZABETH BENTLEY Kathryn S.Olmsted The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 4 of 284 © 2002 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Set in Charter, Champion, and Justlefthand types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red spy queen : a biography of Elizabeth Bentley / by Kathryn S. Olmsted. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2739-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bentley, Elizabeth. 2. Women communists—United States—Biography. 3. Communism—United States— 1917– 4. Intelligence service—Soviet Union. 5. Espionage—Soviet Union. 6. Informers—United States—Biography. I. Title. hx84.b384 o45 2002 327.1247073'092—dc21 2002002824 0605040302 54321 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 5 of 284 To 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet my mother, Joane, and the memory of my father, Alvin Olmsted Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 6 of 284 7 of 284 Contents Preface ix 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1. -

40Th Anniveisafv of Vistory of Anti-Japanese War Il8 ^!^Iin<I Lue

No. 32 August 12, 1985 A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS 40th Anniveisafv of Vistory of Anti-Japanese War il8 ^!^iin<i lUe PBBylaBfi SPOTLIQHT 0 'it •> An artisan passes his skills Tin incense burners. onto a young worker. Tin Handicraft Articles in Yunnan Province Gejiu tin handicraft has a history of more than 300 years. Through dissolution, modelling, scraping and assemble, the artisans create patterns with distinctive national features on pieces of tin. Besides the art for appreciation, Gejiu also produces many handicraft goods for daily use. The products sell well at home and abroad. Croftswoman polishes fin articles. Tin crane. Various kinds of tin wine vessels. ^^^^^^^^^ BEIJING REVIEW HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK Vol. 28, No. 32 August 12, 1985 Looking Back to World War 11 In China As part of a series commemorating the 40th anniversary of CONTENTS the worldwide victory against fascism, a Beijing Review article epitomizes the 8-year long history of China's anti-Japanese war (1937-45), highlighting the role the Communist-Kuomintang co• NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 operation played in the war (p. 13). Fostering Lofty Communist Ideals LEnERS 5 Army Aims to Cut Ranks by 1 Miliion EVENTS & TRENDS 6-9 The Chinese People's Liberation Army celebrated its 58th 'Star Wars' Must Be Avoided — Deng birthday August 1 on the operating table — by reducing 1 Army Aims to Cut Ranks by 1 million troops. This reduction is being carried out to remedy Million the problem Deng Xiaoping noted in 1975 when he said, "The China, Japan Sign Nuclear Agreement army should have an operation to cut its swelling" (p. -

READING REVOLUTION Thomas Fisher University Rare of Book Toronto Library, Art and Literacy During China’S Cultural Revolution

READING REVOLUTION READING REVOLUTION Art and Literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution HannoSilk 112pg spine= .32 Art and LiteracyCultural Revolution during China’s UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY, 2016 $20.00 Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto Reading Revolution: Art and Literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution Exhibition and catalogue by Jennifer Purtle and Elizabeth Ridolfo with the contribution of Stephen Qiao Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto 21 June – 30 September 2016 Catalogue and exhibition by Jennifer Purtle, Elizabeth Ridolfo, and Stephen Qiao General editors P.J. Carefoote and Philip Oldfield Exhibition installed by Linda Joy Digital photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Permission for the use of Toronto Star copyright photographs by Mark Gayn and Suzanne Gayn, held in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, courtesy Torstar Syndication Services. library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Purtle, Jennifer, 1966-, author, organizer Reading revolution : art and literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution / exhibition and catalogue by Jennifer Purtle, Stephen Qiao, and Elizabeth Ridolfo. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-7727-6119-4 (paperback) 1. Mao, Zedong, 1893-1976—Bibliography—Exhibitions. 2. Literacy— China—History—20th century—Exhibitions. 3. Chinese—Books and reading— History—20th century—Exhibitions. 4. Books and reading—China—History— 20th century—Exhibitions. 5. Propaganda, Communist—China—History— 20th century—Exhibitions. 6. Propaganda, Chinese—History—20th century— Exhibitions. 7. Political posters, Chinese—History—20th century—Exhibitions. 8. Art, Chinese—20th century—Exhibitions. 9. China—History—Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976—Art and the revolution—Exhibitions. 10. China— History—Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976—Propaganda—Exhibitions. -

Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with Specific Reference to the Activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts

Mother Russia and the Socialist Fatherland: Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with specific reference to the activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts by Nancy Butler A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November 2010 Copyright © Nancy Butler, 2010 ii Abstract This dissertation traces a shift in the Communist Party of Canada, from the 1929 to 1935 period of militant class struggle (generally known as the ‘Third Period’) to the 1935-1939 Popular Front Against Fascism, a period in which Communists argued for unity and cooperation with social democrats. The CPC’s appropriation and redeployment of bourgeois gender norms facilitated this shift by bolstering the CPC’s claims to political authority and legitimacy. ‘Woman’ and the gendered interests associated with women—such as peace and prices—became important in the CPC’s war against capitalism. What women represented symbolically, more than who and what women were themselves, became a key element of CPC politics in the Depression decade. Through a close examination of the cultural work of two prominent middle-class female members, Dorothy Livesay, poet, journalist and sometime organizer, and Eugenia (‘Jean’ or ‘Jim’) Watts, reporter, founder of the Theatre of Action, and patron of the Popular Front magazine New Frontier, this thesis utilizes the insights of queer theory, notably those of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Judith Butler, not only to reconstruct both the background and consequences of the CPC’s construction of ‘woman’ in the 1930s, but also to explore the significance of the CPC’s strategic deployment of heteronormative ideas and ideals for these two prominent members of the Party. -

On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis

Socialism and Democracy ISSN: 0885-4300 (Print) 1745-2635 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/csad20 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell To cite this article: Thomas Powell (2018) On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis, Socialism and Democracy, 32:1, 1-22, DOI: 10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 Published online: 17 Apr 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 200 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=csad20 Socialism and Democracy, 2018 Vol. 32, No. 1, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2018.1441118 On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis Thomas Powell I Milton Leitenberg’s biological warfare (BW) hoax theory is not believable. For the past three decades, Leitenberg has paraded the thesis that the allegations of BW use leveled against the US by North Korea and China during the Korean War has all been a nefarious hoax – a grand piece of political theater – deviously orchestrated by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and the swarthy Joseph Stalin. Leitenberg’s thesis epitomizes the deeply embedded racism of America’s Cold War politics. He has enjoyed bounteous support from right-wing academia and quasi-government think tanks. The BW hoax thesis has impacted scholarship and US foreign policy, and it is a major stumbling block to improving US relations with North Korea. In this article I will argue that Leitenberg’s thesis is a house of cards built on forged docu- ments, false claims and fake facts. -

Capitalism Unchallenged : a Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949

CAPITALISM UNCHALLENGED : A SKETCH OF CANADIAN COMMUNISM, 1939 - 1949 Donald William Muldoon B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ DONALD WILLIAM MULDOON 1977 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY February 1977 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Donald William Muldoon Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Capitalism Unchallenged : A Sketch of Canadian Communism, 1939 - 1949. Examining Committee8 ., Chair~ergan: .. * ,,. Mike Fellman I Dr. J. Martin Kitchen senid; Supervisor . - Dr.- --in Fisher - &r. Ivan Avakumovic Professor of History University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for mu1 tiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesi s/Di ssertation : Author : (signature) (name) (date) ABSTRACT The decade following the outbreak of war in September 1939 was a remarkable one for the Communist Party of Canada and its successor the Labor Progressive Party. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-Building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller a Thesis Submitt

'An Ancillary Weapon’: Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2015 Copyright ©Kailey Miller, 2015 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Canada’s cultural approaches toward the Communist world – particularly in the performing arts – and the ways in which the public and private sectors sought to develop Canada’s identity during the Cold War. The first chapter examines how the defection of Igor Gouzenko in 1945 framed the Canadian state’s approach to the security aspects of cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union. Chapters 2 to 4 analyse the socio-economic, political, and international context that shaped Canada's music, classical theatre, and ballet exchanges with communist countries. The final chapter explores Expo ’67’s World Festival of Arts and Entertainment as a significant moment in international and domestic cultural relations. I contend that although focused abroad, Canada’s cultural initiatives served a nation-building purpose at home. For practitioners of Canadian cultural diplomacy, domestic audiences were just as, if not more, important as foreign audiences. ii Acknowledgements My supervisor, Ian McKay, has been an unfailing source of guidance during this process. I could not have done this without him. Thank you, Ian, for teaching me how to be a better writer, editor, and researcher. I only hope I can be half the scholar you are one day. A big thank you to my committee, Karen Dubinsky, Jeffrey Brison, Lynda Jessup, and Robert Teigrob.