An Analysis of Selected Fiction, Non-Fiction, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A War Crime Against an Ally's Civilians: the No Gun Ri Massacre

A WAR CRIME AGAINST AN ALLY'S CIVILIANS: THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE TAE-UNG BAIK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................ 456 I. THE ANATOMY OF THE No GUN Ri CASE ............ 461 A. Summary of the Incident ......................... 461 1. The Korean War (1950-1953) .............. 461 2. Three Night and Four Day Massacre ....... 463 * Research Intern, Human Rights Watch, Asia Division; Notre Dame Law School, LL.M, 2000, cum laude, Notre Dame Law Fellow, 1999-2001; Seoul National University, LL.B., 1990; Columnist, HANGYORE DAILY NEWSPAPER, 1999; Editor, FIDES, Seoul National University College of Law, 1982-1984. Publi- cations: A Dfferent View on the Kwangju Democracy Movement in 1980, THE MONTHLY OF LABOR LIBERATION LrrERATuRE, Seoul, Korea, May 1990. Former prisonerof conscience adopted by Amnesty International in 1992; released in 1998, after six years of solitary confinement. This article is a revised version of my LL.M. thesis. I dedicate this article to the people who helped me to come out of the prison. I would like to thank my academic adviser, Professor Juan E. Mendez, Director of the Center for Civil and Human Rights, for his time and invaluable advice in the course of writing this thesis. I am also greatly indebted to Associate Director Garth Meintjes, for his assistance and emotional support during my study in the Program. I would like to thank Dr. Ada Verloren Themaat and her husband for supplying me with various reading materials and suggesting the title of this work; Professor Dinah Shelton for her lessons and class discussions, which created the theoreti- cal basis for this thesis; and Ms. -

Archival Documentation, Historical Perception, and the No Gun Ri Massacre in the Korean War

RECORDS AND THE UNDERSTANDING OF VIOLENT EVENTS: ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTATION, HISTORICAL PERCEPTION, AND THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE IN THE KOREAN WAR by Donghee Sinn B.A., Chung-Ang University, 1993 M.A., Chung-Ang University, 1996 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Department of Library and Information Science School of Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Donghee Sinn It was defended on July 9, 2007 and approved by Richard J. Cox, Ph.D., DLIS, Advisor Karen F. Gracy, Ph.D., DLIS Ellen G. Detlefsen, Ph.D., DLIS Jeannette A. Bastian, Ph.D., Simmons College Dissertation Director: Richard J. Cox, Ph.D., Advisor ii Copyright © by Donghee Sinn 2007 iii RECORDS AND THE UNDERSTANDING OF VIOLENT EVENTS: ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTATION, HISTORICAL PERCEPTION, AND THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE IN THE KOREAN WAR Donghee Sinn, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 The archival community has long shown an interest in documenting history, and it has been assumed that archival materials are one of the major sources of historical research. However, little is known about how much impact archival holdings actually have on historical research, what role they play in building public knowledge about a historical event and how they contribute to the process of recording history. The case of the No Gun Ri incident provides a good example of how archival materials play a role in historical discussions and a good opportunity to look at archival contributions. -

Korean War Timeline America's Forgotten War by Kallie Szczepanski, About.Com Guide

Korean War Timeline America's Forgotten War By Kallie Szczepanski, About.com Guide At the close of World War II, the victorious Allied Powers did not know what to do with the Korean Peninsula. Korea had been a Japanese colony since the late nineteenth century, so westerners thought the country incapable of self-rule. The Korean people, however, were eager to re-establish an independent nation of Korea. Background to the Korean War: July 1945 - June 1950 Library of Congress Potsdam Conference, Russians invade Manchuria and Korea, US accepts Japanese surrender, North Korean People's Army activated, U.S. withdraws from Korea, Republic of Korea founded, North Korea claims entire peninsula, Secretary of State Acheson puts Korea outside U.S. security cordon, North Korea fires on South, North Korea declares war July 24, 1945- President Truman asks for Russian aid against Japan, Potsdam Aug. 8, 1945- 120,000 Russian troops invade Manchuria and Korea Sept. 9, 1945- U.S. accept surrender of Japanese south of 38th Parallel Feb. 8, 1948- North Korean People's Army (NKA) activated April 8, 1948- U.S. troops withdraw from Korea Aug. 15, 1948- Republic of Korea founded. Syngman Rhee elected president. Sept. 9, 1948- Democratic People's Republic (N. Korea) claims entire peninsula Jan. 12, 1950- Sec. of State Acheson says Korea is outside US security cordon June 25, 1950- 4 am, North Korea opens fire on South Korea over 38th Parallel June 25, 1950- 11 am, North Korea declares war on South Korea North Korea's Ground Assault Begins: June - July 1950 Department of Defense / National Archives UN Security Council calls for ceasefire, South Korean President flees Seoul, UN Security Council pledges military help for South Korea, U.S. -

Depictions of the Korean War: Picasso to North Korean Propaganda

Depictions of the Korean War: Picasso to North Korean Propaganda Spanning from the early to mid-twentieth century, Korea was subject to the colonial rule of Japan. Following the defeat of the Axis powers in the Second World War, Korea was liberated from the colonial era that racked its people for thirty-five-years (“Massacre at Nogun-ri"). In Japan’s place, the United States and the Soviet Union moved in and occupied, respectively, the South and North Korean territories, which were divided along an arbitrary boundary at the 38th parallel (Williams). The world’s superpowers similarly divided defeated Germany and the United States would go on to promote a two-state solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The divisions of Korea and Germany, results of the ideological clash between the democratic United States and the communist Soviet Union, set the stage for the ensuing Cold War. On the 25th of June in 1950, North Korean forces, with support from the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea, initiating the Korean, or “Forgotten,” War. Warfare continued until 1953, when an armistice was signed between Chinese and North Korean military commanders and the U.S.-led United Nations Command (Williams). Notably, South Korea was not a signatory of the armistice; South Korea’s exclusion highlights the unusual circumstance that the people of Korea, a people with a shared history, were divided by the United States and the Soviet Union and incited by the super powers to fight amongst themselves in a proxy war between democracy and communism (Young-na Kim). Though depictions of the Korean War are inextricably tied to the political and social ideologies that launched the peninsula into conflict, no matter an artist’s background, his work imparts upon the viewer the indiscriminate ruination the war brought to the people of Korea. -

No Gun Ri Massacre and the Battle of Changjin Reservoir: the Korean War in Lark and Termite and the Coldest Night

【연구논문】 No Gun Ri Massacre and The Battle of Changjin Reservoir: The Korean War in Lark and Termite and The Coldest Night Jae Eun Yoo (Hanyang University) A few days after the 9/11 terrorist attack, scholars of history noted, with much concern, a fierce revival of the Cold War rhetoric. This was first observed in President Bush’s speeches and then quickly spread to official government discourses, media, and popular culture. In various studies of the post-9/11 America, historians such as Mary Dudziak, Marilyn Young, Amy Kaplan, Elaine Tyler May, and Bruce Cumings argue that the striking similarity between the rhetoric employed by the Bush administration and the cold war propaganda of the 1950s testify to the strength of the Cold War legacies. In other words, official and popular responses to 9/11 in the U.S. closely followed the protocols and beliefs formed and practiced in the earlier era of crisis. For instance, May points out that it was “during the cold war” that “the apparatus of wartime” became “a permanent feature of American life” 162 Jae Eun Yoo not only as rhetorical, but as a societal structuring principle” (9/11 220). If, as Jodi Kim argues, the Cold War has produceda hermeneutics peculiar to its social and international conditions, the same paradigm continues to shape the U.S. and its international relations today. The return of the Cold War’s political and cultural paradigm in the days following 9/11 manifests the often unnoticed fact that the legacies of the Cold War continues to exert their power at present; the recognition of such lasting influences of the Cold War era appears to have triggered a renewed interest in re-interpreting the historical period that has been popularly considered as terminated in triumph. -

Bruce Cumings, the Korean

THE KOREAN WAR clan A9:4 A HISTORY ( toot ie let .•-,• ••% ale draa. • 0%1. • .„ \ •r• • • di 11111 1 41'• di• wrsn..."7 • -s. ve,„411p- • dm0 41N-Nitio6 u". •••• -- 411 • ose - r 011.,r•rw••••••• ate,tit 0it it& ado tem.........,111111111nrra° 1 40 Of ••••••—•S‘ 11••••••••••••••• 4,1••••••• o CUMINGS' •IP • AABOUTBOUT THE AAUTHORUTHOR BRUCE CCUMINGSUMINGS is the Gustavus F. and Ann M.M. Swift DistinguishedDistinguished Service ProfessorProfessor inin HistoryHistory atat the University ofof ChicagoChicago and specializesspecializes inin modernmodem KoreanKorean history,history, internationalinternational history,history, andand EastEast AsianAsian–American–American relations. 2010 Modern LibraryLibrary EditionEdition CopyrightCopyright CD© 2010 by Bruce Cumings Maps copyrightcopyright ©0 2010 by Mapping Specialists AllAll rights reserved. Published in the United States by Modern Library,Library, an imprintimprint ofof TheThe Random HouseHouse PublishingPublishing Group,Group, a division ofof RandomRandom House, Inc., New York.York. MODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER DesignDesign areare registeredregistered trademarkstrademarks ofof RandomRandom House,House, Inc.Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGINGCATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION-IN-PUBLICATION DATADATA Cumings,Cumings, Bruce TheThe KoreanKorean War/BruceWar/Bruce Cumings. p. cm.cm.—(A—(A modern librarylibrary chronicleschronicles book)book) eISBN:eISBN: 978-0-679-60378-8978-0-679-60378-8 1.1. Korean War, 1950-1953.1950–1953. 22. KoreanKorean War, 19501950-1953—United–1953—United States. 3. Korean War,War, 19501950-1953—Social–1953—Social aspectsaspects—United—United States. I. Title. DS918.C75D5918.C75 2010 951 951.904 .9042—dc22′2—dc22 2010005629 2010005629 www.modernlibrary.comwww.modemlibrary.com v3.0 CHRONOLOGY 2333 B.C.B.C. Mythical Mythical founding ofof thethe Korean nationnation byby Tangun and hishis bear wifewife. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

The Bible and Empire in the Divided Korean Peninsula in Search for a Theological Imagination for Just Peace

University of Dublin Trinity College The Bible and Empire in the Divided Korean Peninsula In Search for a Theological Imagination for Just Peace A Dissertation Submitted For the Degree of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY By Youngseop Lim Irish School of Ecumenics February 2021 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Signed: _____________________________________ Date: _______________________________________ iii Summary The major objective of this thesis is to examine the relationship between biblical interpretation and imperialism in the context of the Korean conflict. This study takes its starting point in the questions of what caused the Korean conflict, and what role the Bible has played in the divided Korean church and society. In order to find answers to these questions, this study is carried out in several steps. The first step is to explore just peace and imperial peace in the Bible as a conceptual framework. The second step seeks to reconstruct the history of Korean Christianity, the relationship between church and state, and the impact of American church and politics from postcolonial perspective. As the third step, this study focuses on the homiletical discourses of Korean megachurches in terms of their relation to the dominant ideologies, such as anticommunism, national security, pro-Americanism, and economic prosperity. -

Looking Back While Moving Forward: the Evolution of Truth Commissions in Korea

Looking Back While Moving Forward: The Evolution of Truth Commissions in Korea Andrew Wolman* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 27 II. HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS ................................................................ 30 A. 1945-1987: Authoritarianism and Failed Commissions ............. 33 B. 1987-2003: Democratic Transition and the First Truth Commissions .............................................................................. 35 C. 2003-2008: Roh Moo Hyun and a Full Embrace of Truth Commissions .............................................................................. 38 1. Commissions Dealing with the Japanese Colonial Era and Earlier .................................................................................. 39 2. Commissions dealing with the Authoritarian Era ............... 41 III. TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION OF KOREA ...................... 43 A. Mandate ...................................................................................... 44 B. Composition ............................................................................... 45 C. Functions and Powers ................................................................. 46 D. Findings ...................................................................................... 47 E. Recommendations ...................................................................... 48 IV. TRUTH COMMISSIONS UNDER LEE MYUNG BAK (2008-2011) ............ 49 V. CHARACTERISTICS OF KOREAN TRUTH COMMISSIONS -

Neasialookinside.Pdf

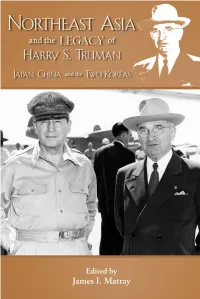

The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in Northeast Asia The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 8 Based on the Eighth Truman Legacy Symposium The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas May 2010 Key West, Florida Edited by James I. Matray Copyright © 2012 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman and General MacArthur at Wake Island, October 15, 1950 (HSTL 67-434). Cover design: Katie Best Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Truman Legacy Symposium (8th : 2010 : Key West, Fla.) Northeast Asia and the legacy of Harry S. Truman : Japan, China, and the two Koreas / edited by James I. Matray. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; volume 8) “Based on the eighth Truman Legacy Symposium, The legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the two Koreas, May, 2010, Key West, Florida.” Includes index. 1. East Asia—Relations—United States—Congresses. 2. United States—Relations— East Asia—Congresses. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1945–1953—Congresses. 4. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Congresses. I. Matray, James Irving, 1948–, editor of compilation. II. Title. DS518.8.T69 2010 327.507309'044—dc23 2012011870 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48– 1992. To Amanda Jane Matray A Master Teacher Contents Illustrations .........................................ix Preface ..............................................xi General Editor’s Preface .............................xiii Introduction .........................................1 Mild about Harry— President Harry S. -

Chinese Experience of the Korean War

> Review Chinese experience of the Korean War Ha Jin. 2004. War Trash. New York: Pantheon Books, 352 pages, ISBN 0 375 42276 5 oner learns to read, which in the muted armed only with bamboo spears and tones of the novel, brings satisfaction to shouts of ‘Mansei!’ (p.187). This epi- the narrator. Rarely, however, are emo- sode, like other repudiations of proletar- tions overplayed. While homesickness ian Korean nationalism, demonstrated among the troops receives sympathetic a deep need among the prisoners for treatment, this text seldom wallows in images of a dominant North Korea, as sentimentality. seen in the accompanying drawing. In the midst of prison camp struggles, Ha Like the 2,000,000 mainland Chinese Jin credits the Americans their share of who were thrust into Korea as ‘volun- brutality, but does not spare the prison- teers’, the narrator encounters an array ers for their own folly. Preparing for an of nationalities, testifying to Korea’s all-out rumble with the guards, Chinese inundation by foreign soldiers. Ameri- prisoners create signs reading ‘Respect cans appear as solicitous doctors, embat- the Geneva Convention!’ even as they tled black soldiers sympathetic to com- sharpen their shanks. munist doctrine, and angry sergeants capable of torture. No one communi- The Chinese-North Korean camara- cates particularly well, and language derie that pervades War Trash exists barriers appear frequently, reminding today only in propaganda artefacts and the reader that, for the Chinese troops wartime kitsch hawked by vendors who trudged across the Yalu River and along the northern bank of the Yalu into the pockmarked netherworld of the River. -

War Trash Free

FREE WAR TRASH PDF Ha Jin | 352 pages | 01 Aug 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9781400075799 | English | New York, United States War Trash by Ha Jin: | : Books A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality study guides that feature detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, quotes, and essay topics. War Trash Ha Jin. Transform this Plot Summary into a Study Guide. War Trash is a historical novel by Ha Jin. The book received widespread critical acclaim upon publication and received a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Ha Jin is the pen name War Trash Jin Xuefei. He is a short story writer, English professor, poet, and novelist. He typically writes about China in English for political reasons. He is best known for his historically accurate world building and his imaginative writing. War Trash begins in during the Korean War. He does not like Communism, but he is forced to accept it as a political reality. As a teenager, he trained as a cadet at the Huangpu Military Academy. Before the Communists seized control of China, the Nationalists controlled the academy; Yuan enjoyed serving under them. Thanks to political pressure, he must now support North Korea in the war effort against South Korea. North Korea has Chinese backing. The academy sends him to Korea where he must serve in the th Division because, unlike most Chinese officers, he speaks and reads enough English to act as a translator. Yuan wants to go home and follow his own political beliefs. He does not expect Tao to wait for him because he has no idea when he will be home again.