Report from Practically Somewhere: Liberland, Sovereignty, and Norm Contestation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regime Crises, Political Exclusion and Indiscriminate Violence in Africa

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: RISKING WAR: REGIME CRISES, POLITICAL EXCLUSION AND INDISCRIMINATE VIOLENCE IN AFRICA Philip Gregory Roessler, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Directed By: Professor Mark I. Lichbach Department of Government and Politics Between 1956 and 1999 one-third of the civil wars in the world occurred in sub- Saharan Africa. The prevailing explanation given to account for this fact is the economic weakness of African states. While low income is a robust determinant of civil war onset in global models, it is not as precise a predictor within sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, I argue that civil war is often a consequence of how African rulers respond to threats to regime survival, such as failed coups d’etat and other regime crises. In the wake of regime crises, rulers, concerned by their tenuous hold on power, seek to reduce the risk of future coups by eliminating disloyal agents from within the government and increasing spoils for more trusted clients to try to guarantee their support should another coup or threat materialize. The problem for the ruler is distinguishing loyal agents from traitors. To overcome this information problem rulers often use ethnicity as a cue to restructure their ruling networks, excluding perceived ‘ethnic enemies’ from spoils. The consequence of such ethnic exclusion is that, due to the weakness of formal state structures, the ruler forfeits his leverage over and information about such societal groups, undermining the government’s ability to effectively prevent and contain violent mobilization and increasing the risk of civil war. To test this hypothesis, I employ a nested research design. -

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Ted Geltner Journal of Magazine Media, Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2012, (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jmm.2012.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/773721/summary [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 07:15 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Literary War Journalism Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Jacksonville University [email protected] Ted Geltner, Valdosta State University [email protected] Abstract Relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the ways literary journalists construct meaning within their narratives. This article employed rhetorical framing analysis to discover embedded meaning within the text of John Sack’s Gulf War Esquire articles. Analysis revealed several dominant frames that in turn helped construct an overarching master narrative—the “takeaway,” to use a journalistic term. The study concludes that Sack’s literary approach to war reportage helped create meaning for readers and acted as a valuable supplement to conventional coverage of the war. Keywords: Desert Storm, Esquire, framing, John Sack, literary journalism, war reporting Introduction Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war. —Carl von Clausewitz Long before such present-day literary journalists as Rolling Stone’s Evan Wright penned Generation Kill (2004) and Chris Ayres of the London Times gave us 2005’s War Reporting for Cowards—their poignant, gritty, and sometimes hilarious tales of embedded life with U.S. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

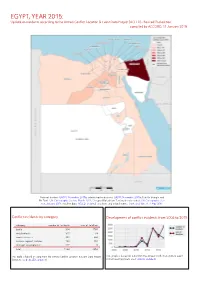

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Micronational Club Starter Packet

2019 Blount County Micronational Club Calendar Have you ever dreamed of ruling over your own country? Here’s your chance! What will the laws, customs, and history be? You decide. What will the flag, coins, and postage stamps look like? You will create them. With a different project each week, you’ll build an empire! On December 21, you can present your creations at the Micronational Fair. Recommended for ages 8 to 18. Thursday Topic Project Brainstorm at Home 09-05 @ 4:00 (in What is a country? / Real Micronations / Brainstorming Name / Vexillology (your flag) Sept.) What makes a good flag? Sheet 09-12 Name / Vexillology Flag Geography (your map) 09-19 Geography Map Theme / Declaration of Independence / Symbols / Motto 09-26 Theme / Declaration of Independence / Seal Constitution / Laws Symbols / Motto 10-03 @ 4:30 Constitution / Laws Coins Economics (Oct-Dec) 10-10 Economics Currency Fashion 10-17 Fashion Sash Crowns / Sports / Awards 10-24 Sports Crown / Trophy / Folklore Medals 10-31 Folklore Monster Stamps / Customs 11-07 Infrastructure Stamps / Passports Language 11-14 Language Language Monument 11-21 Monuments Model Music ThanksGive no no no 12-05 Music Song Holidays 12-12 Holidays Calendar Multinational Fair 12-19 no no no Sat. 12-21 / @ Multinational Fair Multinational Fair Diplomacy 1:00 Other ideas: Micronational Olympics? Some of the projects and themes may change. This is your club. I want to hear your ideas! Contact: Clay Kriese Youth Services Specialist 865-273-1414 [email protected] Make Your Own Micronation Worksheet 2019 Blount County Micronational Club Use this sheet (and a pencil) to help you brainstorm ideas for your new country. -

Small States & Territories, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2019, Pp. 183-194 Oecusse And

Small States & Territories, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2019, pp. 183-194 Oecusse and the Sultanate of Occussi-Ambeno: Pranksterism, misrepresentation and micronationality Philip Hayward School of Communications University of Technology Sydney Australia [email protected] Abstract: Occussi-Ambeno, a fictional sultanate initially conceived by Aotearoan/New Zealander anarchist artist Bruce Grenville in 1968 and represented and developed by him and others over the last fifty years, is notable as both an early example of a virtual micronation (i.e. a type that does not attempt to enact itself within the physical territory it claims) and as an entity affixed to an entire pre-existent territory (in the case of the Sultanate of Occussi- Ambeno, that of Oecusse on the north-west coast of the island of Timor). The latter aspect is pertinent in that however imaginary the micronation is, its association with a region of a small state raises questions concerning the ethics of (mis)representation. This is particularly pertinent in the case of Oecusse, which was occupied by Indonesian forces in 1975 and had its distinct identity subsumed within the Indonesian state until Timor-Leste (and Oecusse as its exclave) successfully gained independence in 2002. Discussions in the article compare the anarcho- pranksterist impulse behind the creation of the Sultanate of Occussi-Ambeno and its manifestation in visual media – primarily through the design and production of ‘artistamps’ (faux postage stamps) – to related economic and socio-political contexts. Keywords: artistamps, Indonesia, micronation, misrepresentation, Occussi-Ambeno, Oecusse, Portugal, Timor, Timor Leste © 2019 – Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta, Malta. -

Small States & Territories, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2019, Pp. 183-194 Oecusse and the Sultanate of Occussi-Ambeno

Small States & Territories, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2019, pp. 183-194 Oecusse and the Sultanate of Occussi-Ambeno: Pranksterism, Misrepresentation and Micronationality Philip Hayward School of Communications University of Technology Sydney Australia [email protected] Abstract: Occussi-Ambeno, a fictional sultanate initially conceived by Aotearoan/New Zealander anarchist artist Bruce Grenville in 1968 and represented and developed by him and others over the last fifty years, is notable as both an early example of a virtual micronation (i.e. a type that does not attempt to enact itself within the physical territory it claims) and as an entity affixed to an entire pre-existent territory (in the case of the Sultanate of Occussi- Ambeno, that of Oecusse on the north-west coast of the island of Timor). The latter aspect is pertinent in that however imaginary the micronation is, its association with a region of a small state raises questions concerning the ethics of (mis)representation. This is particularly pertinent in the case of Oecusse, which was occupied by Indonesian forces in 1975 and had its distinct identity subsumed within the Indonesian state until Timor-Leste (and Oecusse as its exclave) successfully gained independence in 2002. Discussions in the article compare the anarcho- pranksterist impulse behind the creation of the Sultanate of Occussi-Ambeno and its manifestation in visual media – primarily through the design and production of ‘artistamps’ (faux postage stamps) – to related economic and socio-political contexts. Keywords: artistamps, Indonesia, micronation, misrepresentation, Occussi-Ambeno, Oecusse, Portugal, Timor, Timor Leste © 2019 – Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta, Malta. -

Ádány Tamás Vince MIKRONEMZETI TÖREKVÉSEK a NEMZETKÖZI

Pázmány Law Working Papers 2015/11 Ádány Tamás Vince MIKRONEMZETI TÖREKVÉSEK A NEMZETKÖZI JOGI ÁLLAMFOGALOM TÜKRÉBEN Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Pázmány Péter Catholic University Budapest http://www.plwp.jak.ppke.hu/ 1 Mikronemzeti törekvések a nemzetközi jogi államfogalom tükrében „Ebben az intézményben mindenki nyugodtan élhetett rögeszméje szerint, ha ezt csendben tette, és a többi beteget nem bántotta.”1 Néhány kilométernyire a magyar határtól Horvátország és Szerbia között a két ország közötti határ megállapításra vonatkozó elvek határozatlansága, illetve a Duna medrének változása egy látszólagos „senki földjét” hozott létre a környékbeliek által Sziga néven ismert területen, ahol e sorok írásának idején egy cseh állampolgár kezdeményezésére néhány lelkes magánszemély Liberland néven új állam létrehozására törekszik.2 Ez a kísérlet a magyar közvélemény figyelmét is a nemzetközi jognak egyes, a nagyközönség előtt ritkán tárgyalt kérdéseire irányította. A Vít Jedlička úr által létrehozni kívánt állam nem példa nélküli törekvés: a jelenséget, amikor néhány fő – jellemzően egy család vagy baráti kör – egy vitatható jogállású területen saját szuverenitását deklarálja, törekvése szerint új államot hozva ezzel létre, mikronemzetként szokták leírni különböző népszerűsítő fórumokon. A jelenség leírására használt modern fogalom megalkotójaként többen (ha nem is tévesen, de legalábbis erősen túlozva)3 egy bizonyos Robert Ben Medisont jelölnek meg, aki (a közvélekedés szerint egyébként Milwaukee-ban található) hálószobáját tekintette önálló -

Paolo Barberi, Graziano Graziani Script

CATEGORY: DOCUMENTARY SERIES DIRECTION: PAOLO BARBERI, GRAZIANO GRAZIANI SCRIPT: GRAZIANO GRAZIANI LENGTH: 52’ X 8 EPISODES FORMAT: 4K PRODUCTION: ESPLORARE LA METROPOLI LANGUAGE: ENGLISH BUDGET: IN DEVELOPMENT STATUS: IN DEVELOPMENT www.nacne.it www.esplorarelametropoli.it Phone: 0039 328 59.95.253 Phone: 0039 347 42.30.644 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] SUBJECT There are many reasons for founding a nation: idealism, goliardery, politics, even tax evasion. Here are the most strange and evocative cases of a much wider practice than one can imagine: to declare the indepen- dence of a microscopic part of a territory and to proclaim oneself a king or a president, even if only in your own home. Few people know, for example, that in addition to San Marino and the Vatican, there are in Italy a country and an island that have absolute sovereignty over their territories, based on rights acquired before the unification of Italy; or that a nation has been founded in Australia to protect the rights of homosexuals, while in Africa and South America some “non-existent states” have declared independence for the sole purpose of issuing counterfeit treasury bonds. This series of documentaries wants to be an atlas of stories and characters, a geography of places halfway between reality and imagination. Places that often dissolve themselves with the disappearance of their founder. Small epics that, for better or for worse, lead to paroxysm the irreducible desire for independence and autonomy of human beings. ATLAS OF MICRONATION is articulated as a series of 8 self-conclusive episodes, each dedicated to the story of a single micronation. -

Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-Related Publications

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Finding Aids Special Collections Department 1-31-2020 Guide to MS677 Vietnam War-related publications Carolina Mercado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/finding_aid This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guide to MS 677 Vietnam War-related publications 1962 – 2010s Span Dates, 1966 – 1980s Bulk Dates 3 feet (linear) Inventory by Carolina Mercado July 30, 2019; January 31, 2020 Donated by Howard McCord and Dennis Bixler-Marquez. Citation: Vietnam War-related publications, MS677, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department. The University of Texas at El Paso Library. C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department University of Texas at El Paso Historical Sketch The Vietnam War (1954 – 1975) was a military conflict between the communist North Vietnamese (Viet Cong) and its allies and the government of South Vietnam and its allies (mainly the United States). The North Vietnamese sought to unify Vietnam under a communist regime, while South Vietnam wanted to retain its government, which was aligned with the West. The war was also a result of the ongoing Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. On July 2, 1976 the North Vietnamese united the country after the South Vietnamese government surrendered on April 30. Millions of soldiers and civilians were killed during the Vietnam War. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, “The Vietnam War,” accessed on January 31, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War] Series Description or Arrangement This collection was left in the order found by the archivist. -

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (But Still So Far): Assessing Liberlandâ•Žs Claim of Statehood

Chicago Journal of International Law Volume 17 Number 1 Article 10 7-1-2016 Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (But Still So Far): Assessing Liberland’s Claim of Statehood Gabriel Rossman Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil Recommended Citation Rossman, Gabriel (2016) "Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (But Still So Far): Assessing Liberland’s Claim of Statehood," Chicago Journal of International Law: Vol. 17: No. 1, Article 10. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol17/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (But Still So Far): Assessing Liberland’s Claim of Statehood Gabriel Rossman Abstract This Comment analyzes the statehood aspirations of Liberland, a self-proclaimed microstate nestled on a tract of disputed territory between Serbia and Croatia. Customary international law, the Montevideo Criteria, and alternative modalities of recognition are discussed as potential avenues for Liberland to gain recognition. The theoretical and practical merits of these theories are explored. Ultimately, Liberland has two potential avenues for obtaining recognition. First, Liberland could convince the international community that the land it claims is terra nullius and satisfies the Montevideo Criteria. Second, Liberland could obtain constitutive recognition by the international community. It is unlikely that Liberland will be able to obtain recognition through either of these avenues. Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 308 II. A Brief History of Liberland .............................................................................. -

LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A

LiteraryStudies Journalism Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 Return address: Literary Journalism Studies State University of New York at Cortland Department of Communication Studies P.O. Box 2000 LJS Cortland, New York 13045-0900 U.S.A. Literary Journalism Studies Inaugural Issue The Problem and the Promise of Literary Journalism Studies by Norman Sims An exclusive excerpt from the soon-to-be-released narrative nonfiction account, published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath by Michael and Elizabeth Norman Writing Narrative Portraiture by Michael Norman South: Where Travel Meets Literary Journalism by Isabel Soares Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2009 2009 Spring 1, No. 1, Vol. “My Story Is Always Escaping into Oher People” by Robert Alexander Differently Drawn Boundaries of the Permissible by Beate Josephi and Christine Müller Recovering the Peculiar Life and Times of Tom Hedley and of Canadian New Journalism by Bill Reynolds Published at the Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University 1845 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, U.S.A. The Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies On the Cover he ghost image in the background of our cover is based on this iconic photo Tof American prisoners-of-war, hands bound behind their backs, who took part in the 1942 Bataan Death March. The Death March is the subject of Michael and Elizabeth M. Norman’s forthcoming Tears in the Darkness, pub- lished by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Excerpts begin on page 33, followed by an essay by Michael Norman on the challenges of writing the book, which required ten years of research, travel, and interviewing American and Filipino surivivors of the march, as well as Japanese participants. -

Ifbb Elite Professional Qualifier 2021 Ifbb World

IFBB ELITE PROFESSIONAL QUALIFIER 2021 IFBB WORLD RANKING EVENT WELCOME Dear Brothers, Friends & Colleagues, The Egyptian Federation of Bodybuilding & Fitness (E.F.B.F) is proudly inviting all athletes from IFBB-affiliated National Federations from Europe, Africa and Asia to participate in the Muscle Tech Egypt IFBB Diamond Cup that will be held in the wonderful city of Cairo, Egypt during the period from the 18th till the 20th of February, 2021. Special Thanks to Dr. Rafael Santonja, the President of the International Federation of Bodybuilding and Fitness (IFBB) for his continuous support for our beloved sport and his special care of these championships. We are all proud of our great leader whom we learned from him a lot, and experienced from his great talented character. I would also like to convey my sincere thanks & gratitude to Mr. Abdelazeem Hegazy, the Chairman of the Muscletech Egypt for sponsoring such an important sports event, confirming his vision to support bodybuilding sport as a healthy lifestyle. The event will include Junior Men’s Bodybuilding, Men’s Bodybuilding, Men’s Classic Physique, Men’s Physique & Masters Men’s Bodybuilding. Once again welcome to the marvelous Cairo; one of the most attractive cities all over the world; and I hope that your stay in our country will be a memory of joy and pleasure. Dr. Eng. Adel Fahim Executive Assistant & Vice-President, IFBB President Egyptian, Arab & African Federations ABOUT EGYPT: Egypt, country located in the northeastern corner of Africa. Egypt’s heartland, the Nile River valley and delta, was the home of one of the principal civilizations of the ancient Middle East and, like Mesopotamia farther east, was the site of one of the world’s earliest urban and literate societies.