Chinese-Australian Fiction: a Hybrid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Answers to Questions on Notice: Supplementary Budget Estimates 2014-15

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGET ESTIMATES 2014-15 Finance Portfolio Department/Agency: All Outcome/Program: General Topic: Staffing profile Senator: Ludwig Question reference number: F101 Type of question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: Wednesday, 31 December 2014 Number of pages: 9 Question: Since Budget Estimates in May 2014: 1. Has there been any change to the staffing profile of the department/agency? 2. Provide a list of changes to staffing numbers, broken down by classification level, division, home base location (including town/city and state). Answer: Department/ Response Agency Finance Yes, refer to Attachment A. Australian Yes, refer to Attachment B. Electoral Commission ComSuper 1. – 2. For the period 28 May to 31 October 2014, the changes to the staffing profile are shown in the two tables below. Note that all ComSuper staff are located in the ACT. Change Branch May 14 Oct 14 (May - Oct 14) Business and Information Services 105 96 -9 Business Reform 13 15 2 Corporate Overheads 3 2 -1 Corporate Strategy and Coordination 24 22 -2 Executive & Exec Support 3 3 0 Financial Management 43 40 -3 Member Benefits and Account Management 126 124 -2 Member and Employer Access and 132 114 -18 Page 1 of 9 Department/ Response Agency Support People and Governance 49 45 -4 Total 498 461 -37 Change Branch May 14 Oct 14 (May - Oct 14) APS Level 1 2 1 -1 APS Level 2 5 4 -1 APS Level 3 39 31 -8 APS Level 4 101 96 -5 APS Level 5 101 98 -3 APS Level 6 105 98 -7 Executive Level 1 103 94 -9 Executive Level 2 34 31 -3 SES 1 7 7 0 CEO 1 1 0 Total 498 461 -37 Commonwealth 1. -

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism

The Rise and Fall of Australian Maoism By Xiaoxiao Xie Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Studies School of Social Science Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide October 2016 Table of Contents Declaration II Abstract III Acknowledgments V Glossary XV Chapter One Introduction 01 Chapter Two Powell’s Flowing ‘Rivers of Blood’ and the Rise of the ‘Dark Nations’ 22 Chapter Three The ‘Wind from the East’ and the Birth of the ‘First’ Australian Maoists 66 Chapter Four ‘Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party’ 130 Chapter Five ‘Things Are Beginning to Change’: Struggles Against the turning Tide in Australia 178 Chapter Six ‘Continuous Revolution’ in the name of ‘Mango Mao’ and the ‘death’ of the last Australian Maoist 220 Conclusion 260 Bibliography 265 I Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

Victorian and ACT Electoral Boundary Redistribution

Barton Deakin Brief: Victorian and ACT Electoral Boundary Redistribution 9 April 2018 Last week, the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’) announced substantial redistributions for the Electorate Divisions in Victoria and the ACT. The redistribution creates a third Federal seat in the ACT and an additional seat in Victoria. These new seats are accompanied by substantial boundary changes in Victoria and the ACT. ABC electoral analyst Antony Green has predicted that the redistribution would notionally give the Australian Labor Party an additional three seats in the next election – the Divisions of Dunkley, Fraser, and Bean – while the seat of Corangamite would become one of the most marginal seats in the country. The proposed changes will now be subject to a consultation period where objections to the changes may be submitted to the AEC. The objection period closes at 6pm May 4 in both the ACT and Victoria. A proposed redistribution for South Australia will be announced on April 13. This Barton Deakin Brief will summarize the key electoral boundary changes in the ACT and Victoria. New Seats The Redistribution Committee has proposed that four of Victoria’s electoral divisions be renamed. Additionally, two new seats are to be created in Victoria and the ACT New Seats Proposed for Victoria and ACT DIVISION OF BEAN (ACT) New seat encompassing much of the former Division of Canberra. The seat will be named after World War I war correspondent Charles Edwin Woodrow Green (1879-1968) DIVISION OF FRASER (VIC) New seat named after former Liberal Party Prime Minister John Malcolm Fraser AC CH GCL (1930-2015), to be located in Melbourne’s western suburbs. -

Bruce Cumings, the Korean

THE KOREAN WAR clan A9:4 A HISTORY ( toot ie let .•-,• ••% ale draa. • 0%1. • .„ \ •r• • • di 11111 1 41'• di• wrsn..."7 • -s. ve,„411p- • dm0 41N-Nitio6 u". •••• -- 411 • ose - r 011.,r•rw••••••• ate,tit 0it it& ado tem.........,111111111nrra° 1 40 Of ••••••—•S‘ 11••••••••••••••• 4,1••••••• o CUMINGS' •IP • AABOUTBOUT THE AAUTHORUTHOR BRUCE CCUMINGSUMINGS is the Gustavus F. and Ann M.M. Swift DistinguishedDistinguished Service ProfessorProfessor inin HistoryHistory atat the University ofof ChicagoChicago and specializesspecializes inin modernmodem KoreanKorean history,history, internationalinternational history,history, andand EastEast AsianAsian–American–American relations. 2010 Modern LibraryLibrary EditionEdition CopyrightCopyright CD© 2010 by Bruce Cumings Maps copyrightcopyright ©0 2010 by Mapping Specialists AllAll rights reserved. Published in the United States by Modern Library,Library, an imprintimprint ofof TheThe Random HouseHouse PublishingPublishing Group,Group, a division ofof RandomRandom House, Inc., New York.York. MODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER DesignDesign areare registeredregistered trademarkstrademarks ofof RandomRandom House,House, Inc.Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGINGCATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION-IN-PUBLICATION DATADATA Cumings,Cumings, Bruce TheThe KoreanKorean War/BruceWar/Bruce Cumings. p. cm.cm.—(A—(A modern librarylibrary chronicleschronicles book)book) eISBN:eISBN: 978-0-679-60378-8978-0-679-60378-8 1.1. Korean War, 1950-1953.1950–1953. 22. KoreanKorean War, 19501950-1953—United–1953—United States. 3. Korean War,War, 19501950-1953—Social–1953—Social aspectsaspects—United—United States. I. Title. DS918.C75D5918.C75 2010 951 951.904 .9042—dc22′2—dc22 2010005629 2010005629 www.modernlibrary.comwww.modemlibrary.com v3.0 CHRONOLOGY 2333 B.C.B.C. Mythical Mythical founding ofof thethe Korean nationnation byby Tangun and hishis bear wifewife. -

Four Decades On, Cultural Revolution Leaves Indelible Imprint on China by Peter Harmsen Tuous Period, They Were Suddenly Told to Posterity

8 Tuesday 16th May, 2006 Special Report Responding to Terrorism their call to demonstrate. TTN is now instigating communal disharmony and more surgical and effective in nature. broadcasting free without subscription, portraying itself as the “saviours of the Sri Lanka needs to balance world per- because Tamils subscribing to the LTTE Tamils” a strategy which has now been ception created by the terrorist attack on television station has hit an all time low. exposed even within Tamil society. It the army commander with that of the Even in Sri Lanka as a whole, the attempts to impose its will on the Tamil perception created by the air force of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), a proxy population by claiming to be the sole rep- republic carrying out air strikes and of the LTTE, has failed to secure even resentative of Tamils. causing several thousand civilian dis- 50% of the Sri Lankan Tamil vote in Sri Copying the concept of the placement albeit unintentionally. Lanka and that’s after ballot box stuffing Palestinian Authority, the LTTE and Britain would not have dreamt of car- as declared by the EU election monitors. their propaganda regularly refers to the rying out air strikes against the IRA in The LTTE are clearly annoyed by the LTTE administered region of Sri Lanka. response to the terrorist assassination of lack of support from Tamils, and their Reality is the LTTE does not administer Lord Mountbatten. It responded by using latest ‘land laws’ aimed at confiscating any region of Sri Lanka. The LTTE phys- other but more deadly surgical methods. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi

AFTERLIVES OF CHINESE COMMUNISM AFTERLIVES OF CHINESE COMMUNISM POLITICAL CONCEPTS FROM MAO TO XI Edited by Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere First published 2019 by ANU Press and Verso Books The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (hardback): 9781788734790 ISBN (paperback): 9781788734769 ISBN (online): 9781760462499 WorldCat (print): 1085370489 WorldCat (online): 1085370850 DOI: 10.22459/ACC.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Note on Visual Material All images in this publication have been fully accredited. As this is a non-commercial publication, certain images have been used under a Creative Commons licence. These images have been sourced from Flickr, Wikipedia Commons and the copyright owner of each original picture is acknowledged and indicated in the source information. Design concept and typesetting by Tommaso Facchin; Illustrations by Marc Verdugo Lopez. Cover design by No Ideas. Cover artwork by Marc Verdugo Lopez. Proofreading by Sharon Strange and Evyn Chesneau Papworth. This edition © 2019 ANU Press and Verso Books Table of Contents Introduction - Christian SORACE, Ivan FRANCESCHINI, and Nicholas LOUBERE 1 1. Aesthetics - Christian SORACE 11 2. Blood Lineage - YI Xiaocuo 17 3. Class Feeling - Haiyan LEE 23 4. Class Struggle - Alessandro RUSSO 29 5. Collectivism - GAO Mobo 37 6. Contradiction - Carlos ROJAS 43 7. Culture - DAI Jinhua 49 8. Cultural Revolution - Patricia M. -

Neasialookinside.Pdf

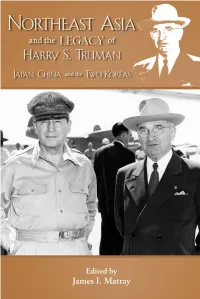

The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in Northeast Asia The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 8 Based on the Eighth Truman Legacy Symposium The Legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas May 2010 Key West, Florida Edited by James I. Matray Copyright © 2012 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman and General MacArthur at Wake Island, October 15, 1950 (HSTL 67-434). Cover design: Katie Best Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Truman Legacy Symposium (8th : 2010 : Key West, Fla.) Northeast Asia and the legacy of Harry S. Truman : Japan, China, and the two Koreas / edited by James I. Matray. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; volume 8) “Based on the eighth Truman Legacy Symposium, The legacy of Harry S. Truman in East Asia: Japan, China, and the two Koreas, May, 2010, Key West, Florida.” Includes index. 1. East Asia—Relations—United States—Congresses. 2. United States—Relations— East Asia—Congresses. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1945–1953—Congresses. 4. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Congresses. I. Matray, James Irving, 1948–, editor of compilation. II. Title. DS518.8.T69 2010 327.507309'044—dc23 2012011870 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48– 1992. To Amanda Jane Matray A Master Teacher Contents Illustrations .........................................ix Preface ..............................................xi General Editor’s Preface .............................xiii Introduction .........................................1 Mild about Harry— President Harry S. -

An Analysis of Selected Fiction, Non-Fiction, And

"PLUNGED BACK WITH REDOUBLED FORCE": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FICTION, NON-FICTION, AND POETRY OF THE KOREAN WAR A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts John Tierney May, 2014 "PLUNGED BACK WITH REDOUBLED FORCE": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FICTION, NON-FICTION, AND POETRY OF THE KOREAN WAR John Tierney Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Faculty Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Patrick Chura Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________________ _____________________________________ Department Coordinator Date Dr. Joseph F. Ceccio _______________________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii DEDICATION To Jonas and his grand empathy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Ji Young for her support and patience these three years. Veronica and Patrick for the diversions. Thanks also to Dr. Mary Biddinger for her advice and encouragement with the writing process, to Dr. Patrick Chura for his time and vote of confidence, to Dr. Joseph Ceccio for his time and advice, and to Dr. Hillary Nunn for her seminar in literary criticism and for her help with editing. A million thanks to Craig Blais, Colleen Tierney, and everyone else who listened to my ideas at the conception of this project. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………………..1 II. IMPERIAL AMERICA AND THE PREDOMINANCE IN MILITARY POWER IN THE KOREAN WAR……………………………………………………………………..........8 Background…………………………………………………………………………........10 Military Readiness…………………………………………………………………….15 Demeanor and Performance………………..…………………………….............18 Brutal Methods…...……………………………………………………………………..20 III. CHAOS IN THE FATHERLAND……………………………………………………………….30 Background.………………………………………………………………………………31 IV.