Harrriman Was Appointed to the Position of Ambassador at Large In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project THEODORE J. C. HEAVNER Interviewed By: Char

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project THEODORE J. C. HEAVNER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 28, 1997 Copyright 2 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Canton, O io Nort western University and (Case) Western Reserve University of Iowa Harvard University U.S. Army - ,orean War Entered Foreign Service - .900 UNESCO .900-.901 Duties State Department - Foreign Service Institute - .902 3ietnamese 4anguage Training Cornell University - Sout east Asia Program .902-.908 Nort versus Sout 3ietnam Saigon, 3ietnam - Political Officer .908-.909 Diem and private armies Relations wit government officials Cinnamon production Ambassador Durbrow 3iet Cong t reat Consular district Duties Ngo Din Can Reporting Cat olic C urc role Diplomatic colleagues Environment 7ontagnards Pleiku 3ietnamese military 1 Tran 3an Don Saigon, 3ietnam - Political Officer .910-.91. 4yndon B. 9o nson visit Ambassador Ale:is 9o nson and Diem ,ennedy;s 3ietnam policy State Department - 3ietnam Working Group .91.-.913 Averell Harriman Counterinsurgency U.S. policy re Nort 3ietnam Strategy options Ot er agency programs Diem regime 3ietnamese loyalties T ieu ,y regime President ,ennedy interest Defoliants Roger Hilsman C ina role State Department - Foreign Service Institute (FSI) .913-.914 Indonesian 4anguage Training 7edan, Indonesia - Consul and Principal Officer .914-.911 Ambassador Howard 9ones Ambassador 7ars all Green Sukarno and communists Anti-U.S. demonstrations Sumatra groups -

Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010

Description of document: Index to the US Department of State Documents Collection, 2010 Requested date: 13-May-2010 Released date: 03-December-2010 Posted date: 09-May-2011 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Officer Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL US Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Notes: This index lists documents the State Department has released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) The number in the right-most column on the released pages indicates the number of microfiche sheets available for each topic/request The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

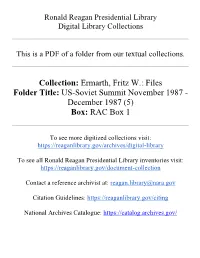

US-Soviet Summit November-December 1987

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Ermarth, Fritz W.: Files Folder Title: US-Soviet Summit November 1987 - December 1987 (5) Box: RAC Box 1 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name ERMATH, FRITZ: FILES Withdrawer MID 4/19/2013 File Folder US - SOVIET SUMMIT: NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1987 (5) FOIA F02-073/5 Box Number RAC BOX 1 COLLINS 85 ID Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions Pages 157588 MEMO ROBERT RISCASSI TO GRANT GREEN 2 11/20/1987 Bl RE SUMMIT 157589 MEMO FRANK CARLUCCI TO THE PRESIDENT 5 11/20/1987 B 1 RE SCOPE PAPER 157590 SCOPE PAPER RE KEY ISSUES FOR THE SUMMIT 7 ND Bl 157591 MEMO FRITZ ERMARTH TO FRANK CARLUCCI 1 11/19/1987 Bl RE SCOPE PAPER 157592 MEMO WILLIAM MATZ TO GRANT GREEN RE 3 11/23/1987 B 1 SUMMIT (W/ATTACHMENTS) The above documents were not referred for declassification review at time of processing Freedom of Information Act• (5 U.S.C. 552(b)J B-1 Natlonal aecurlty claaalfled Information [(b)(1) of the FOIAJ B-2 Releaae would dlacloae Internal personnel rulea and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIAJ B-3 Releaae would -

Download PDF Van Tekst

Memoires 1979-A Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Memoires 1979-A. Papieren Tijger, Breda 2010 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003memo26_01/colofon.php © 2013 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 7 Inleiding Recently I was invited by the television company Het Gesprek to join the host Frits Barend on the programme Dossier BVD. The programme is designed to take a retrospective look at guests who had appeared on the now legendary show, Barend en van Dorp and Willem Oltmans had been a frequent guest. Clips were shown, discussed, and questions followed. Once again the re-occurring theme reared its head. ‘Would Willem be remembered as a great journalist or as a charlatan?’ Without presumption I say that I probably knew Willem better than anyone else, and the word ‘charlatan’ does not enter my vocabulary. I saw Willem as a man who hated lies, hypocrisy and cover-ups. His diaries, meticulously notated, and which he himself referred to as ‘my brain’, speak for themselves. Willem was also capable of being Spartan with detail when the noted facts were painful to him. 19th of May 1979, thirteen years exactly to the day that we first met, he writes of a painful incident and refers to it simply as ‘a sort of rape’. I was the subject of that rape and the same uninvited, explosive sexual attack was forced on me again two weeks later in the home of his mother. We never spoke of it, and so I find it a revealing characteristic of the complex Oltmans brain that he chose to acknowledge his darker sides and demons, albeit without any emotion. -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included. -

Interview with Roger Hilsman

Library of Congress Interview with Roger Hilsman Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ROGER HILSMAN Interviewed by: Paige E. Mulhollan Initial interview date: May 15, 1969 Q: Let's begin by identifying you, Sir. You're Roger Hilsman, and your last official position with the government was as assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern Affairs which you held until of 1964. Is that correct? HILSMAN: No, March 15th. I actually resigned earlier than that, but the President asked me to stay till March 15th while he got a replacement. Q: And you had been director of the INR [Intelligence and Research]from the beginning of the Kennedy Administration until 1963? HILSMAN: Right. Q: So you served about a year in the Far East post. HILSMAN: Just a little over. Q: Did you know Mr. Johnson at all prior to the time you came intthe Kennedy Administration? Had you ever had any contact? Interview with Roger Hilsman http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000512 Library of Congress HILSMAN: I had had some indirect contact with him when he was on Capitol Hill. I was chief of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Legislative Reference Service, and then I was deputy director of the Service. And though I didn't know him personally, I had done some things with some of his staff. It was funny about this, because William S. White, you know, Bill White, was a great friend of the President's. And he's a great friend of mine. -

Interview with Ted Sorensen, President Kennedy's Speechwriter by Sherry and Jenny Thompson, February 2010

Sorensen interview with Jenny and Sherry February 2010 Q. Your relationship to Thompson and his to Kennedy When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, one of the reasons he ran was because at the height of the Cold War he was fearful that the Eisenhower/Dulles foreign policy of massive retaliation might only lead to nuclear war. Your father, Llewellyn Thompson, who had been US ambassador in Moscow during those late 50’s years was I’m quite certain a career a foreign service officer who was appointed I’m not sure what his title was counselor or maybe Ambassador at Large in the State Department. When CMC broke, (and more details in my new book called Councilor: Life at the Edge of History) on Oct. 16 the first of 13 memorable days of 1962. Historians still call them the 13 most dangerous days in the history of mankind. Because a misstep a wrong move could have started a war which would have turned very quickly into a nuclear exchange. And if the first step were Soviets firing tactical nuclear weapons, The United States, would have responded at least with tactical nuclear weapons and once both sides were on that nuclear escalator, they would have moved up to strategic weapons and then to all-out warfare, and the scientists say that the explosion of so many large nuclear weapons in both eastern Europe and in North America would have produced, in addition to the bombardment of 100s of thousands and millions of people in both countries, would have resulted in radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere and in time of every dimension of our planet and would be speed via wind and water and even soil to the far reaches of the planet until that planet was uninhabitable: no plant life, no animal life, no human life, and we you and I would not be talking right now. -

An Nbc News White Paper Vietnam Hindsight Part Ii

AN NBC NEWS WHITE PAPER VIETNAM HINDSIGHT PART II: THE DEATH OF DIEM BROADCAST: WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1971 10:00 - 11:00 CREDITS Opening Title: NBC NEWS WHITE PAPER VIETNAM HINDSIGHT PART II: DEATH OF DIEM Credits: NBC NEWS WHITE PAPER VIETNAM HINDSIGHT Copyright c The National Broadcasting Co., Inc. 1971 All Rights Reserved Produced and Written By FRED FREED Directed by PAMELA HILL Associate Producers ALVIN DAVIS PAMELA HILL Researcher HELEN WHITNEY Production Assistant BARBARA SPENCE Film Researcher JACK GOELMAN Unit Manager KLAUS HEYS Supervising Film Editor DARROLD MURRAY Film Editors MARY ANN MARTIN STUART M. ROSENBERG DAVID J. SAUL JEAN BAGLEY Cameramen STEVE PETROPOULOS WILLIAM RICHARDS Sound JAMES ZOLTOWSKI JOSE VALLE JOHN SINGLETON JEROME GOLD HENRY ROSSEAU IRVING GANS SHELLY FIELMAN Still Pictures by JACQUES LOWE BLACK STAR MAGNUM GEORGES TAMES - THE NEW YORK TIMES THE JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY YOICHI CKOMOTO HORST ?HAAS PEOPLE WHO WERE INTERVIEWED FOR VIETNAM HINDSIGHT IN ORDER OF THEIR APPEARANCE AND POSITION HELD AT THE TIME GEORGE BALL Under-Secretary of State 1961-1966 MAXWELL TAYLOR- Military Adviser to JFK 1961 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs 1962- 64 JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH Ambassador to India 1961-63 DAVID HALBERSTAM Correspondent - New York Times - Vietnam 1962-63 WALT M. ROSTOW Deputy Special Assistant to the President for National Security 1961-64 MME. NHU Wife of Ngo Dinh Nhu, sister-in-law of Ngo Dinh Diem ARTHUR SCHLESINGER Special Assistant to the President 1961-64 PAUL HARKINS US Military Commander - Vietnam 1962-64 • JOHN VANN American Military Adviser in Vietnam MICHAEL FORRESTAL Senior Member - White House National Security Staff 1962-66 ROGER HILSMAN Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs 1963-64 ■ RUFUS PHILLIPS American AID Mission - Vietnam -2- FREDERICK NOLTING U.S. -

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 Finding the HRight Key:" Kennedy and the New Pacific Community 1. William J. Lederer and Eugene Burdick, The Ugly American (New York, 1960), pp. 163, 233. 2. "The United States and Our Future in Asia," Excerpts from the Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy (Hawaii, 1958), JFK Library, Senate Files. 3. Ibid. Championing America's virtue and image abroad, as weil as Amer ican self-interest, always remained a difficult task for Kennedy. See Ronald Nurse, "America Must Not Sleep: The Development of John F. Kennedy's Foreign Policy Attitudes, 1947-1960" (Ph.D. dissertation: Michigan State University, 1971), James Dorsey, "Vietnam 'a can of snakes,' Galbraith told JFK," Boston Globe (28 January 1974), Stephen Pelz, "John F. Kennedy's 1961 Vietnam War Decisions," lournal of Strategie Studies (December 1981), lan McDonald, "Kennedy Files Show President's Dismay at CIA Power," The Times (London, 2 August 1971), JFK Library, Excerpts from Biographical Files. 4. Secretary of State Dean Rusk to Kennedy, 2 February 1961, and "The New Pacific" (Speech in Hawaii, August 1960), JFK Library, POFlBox 111 and Senate Files. 5. John F. Kennedy, Public Papers of the President, 1961) (Washington, D.C., 1961), pp. 174-5. These comments were made during the Presi dent's push to create the "Alliance for Progress" program for the Latin AmericaniCaribbean states. 6. Kennedy, Public Papers ofthe President, 1961, p. 399. 7. Ibid., 1963, p. 652. 8. Kennedy's early cabinet meetings on foreign affairs topics often became energetic discussions on how to win the Cold War. A winning strategy, wh ether in allied favor or not, was acceptable. -

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Association for Diplomatic Studies and Train

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training oreign Affairs Oral History Pro$ect RUFUS PHILLIPS Interviewed by: Ted Gittinger Initial interview date: March 4, 1982 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background University of Virginia Law School Served briefly with CIA US Army, Korean ,ar, Vietnam ,ar Vietnam ,ar 1.5011.52 Saigon 3ilitary 3ission North Vietnamese Catholics Colonel Lansdale Use of rench language Joe Ban4on Soc Trang Province Hanh Diem 3agsaysay Ambassador 5eneral Lawton Collins 6retired7 Liaison Officer Ca 3au operation Operation Brotherhood ilipinos Reoccupation of 8one 5 rench Operation Atlante 5eneral 3ike O9Daniel Colonel Kim Training Relations Instruction 3ission 6TRI37 Viet 3inh evacuation rench1Diem relations Resentment of Viet 3inh 3AA5 Binh :uyen Central Intelligence Agency 6CIA7 1 Vietnamese psywar school Setting up 515 staff Kieu Cong Cung Civil Action Pro$ect AID 3ission Re1organi4ation of Vietnamese army Viet 3inh preparations for resurgence in South Pre1Ho Chi 3inh Trail Civil 5uard Colonel Lansdale Tran Trung Dung 3ontagnards Destabili4ing Viet 3inh regime Almanac incidents Bui An Tuan Vietnam ;uoc Dan Dang 6VN;DD7 Truong Chinh Political Program for Vietnam 5eneral O1Daniel Ambassador Collins/CIA relations Land Reform ,olf Lade$isky Saigon racketeering operations rench anti1US operations Saigon bombing US facilities Howie Simpson Bay Vien rench 5eneral Ely Trinh 3inh Thé Vietnamese/ rench relations Romaine De osse rench deal with Ho Chi -

1961–1963 First Supplement

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES USSRUSSR ANDAND EASTERNEASTERN EUROPE:EUROPE: NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961–1963 FIRST SUPPLEMENT A UPA Collection from National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 USSR and Eastern Europe First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. USSR and Eastern Europe. First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. — (National security files) “Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Nicholas P. Cunningham. ISBN 1-55655-876-7 1. United States—Foreign relations—Soviet Union—Sources. 2. Soviet Union—Foreign relations—United States—Sources. 3. United States—Foreign relations—1961–1963— Sources. 4. National security—United States—History—Sources. 5. Soviet Union— Foreign relations—1953–1975—Sources. 6. Europe, Eastern—Foreign relations—1945– 1989. I. Lester, Robert. II. Cunningham, Nicholas P. III. University Publications of America (Firm) IV. Title. V. Series. E183.8.S65 327.73047'0'09'046—dc22 2005044440 CIP Copyright © 2006 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-876-7. -

John F. Kennedy and the Advisory Effort for Regime Change in South

Imperial Camelot: John F. Kennedy and the Advisory Effort for Regime Change in South Vietnam, 1962-1963 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Millersville University of Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Shane M. Marino © 2018 Shane M. Marino May 2018 This Thesis for the Master of Arts Degree by Shane Michael Marino has been approved on behalf of the Graduate School by Thesis Committee: Dr. John M, McLarnon III (Signature on file) Research Advisor Dr. Tracey Weis (Signature on file) Committee Member Dr. Abam B. Lawrence (Signature on file) Committee Member May 10, 2018 Date ii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS IMPERIAL CAMELOT: JOHN F. KENNEDY AND THE ADIVSORY EFFORT FOR REGIME CHANGE IN SOUTH VIETNAM, 1962-1963 By Shane M. Marino Millersville University, 2018 Millersville, Pennsylvania Directed by Dr. John McLarnon This thesis uses government documents, oral histories, and secondary sources to explore changes in the Kennedy administration’s Vietnam policy to determine the factors that contributed to the decision to support a coup d’état in 1963 that overthrew the President of the Republic of Vietnam and subsequently led to his assassination. The thesis specifically looks to connect administrative changes in organization and personnel to changes in policy that ultimately determined the fate of the Ngo Dinh Diem regime. In general, this thesis reveals that rejection of military intervention led to the adoption of a kind of political aggression that envisioned covert regime change as an acceptable alternative to the use of combat troops.