201429Pap.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

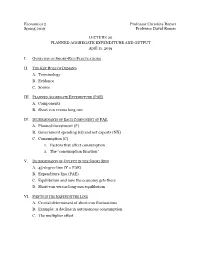

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics -

Economics 102 Fall 2015 Answers to Homework #5 Due December 14, 2015

Economics 102 Fall 2015 Answers to Homework #5 Due December 14, 2015 Directions: The homework will be collected in a box before the large lecture. Please place your name, TA name, and section number on the top of the homework (legibly). Make sure you write your name as it appears on your ID so that you can receive the correct grade. Late homework will not be accepted so make plans ahead of time. Please show your work. Good luck! Please realize that you are essentially creating “your brand” when you submit this homework. Do you want your homework to convey that you are competent, careful, professional? Or, do you want to convey the image that you are careless, sloppy, and less than professional. For the rest of your life you will be creating your brand: please think about what you are saying about yourself when you do any work for someone else! 1) Aggregate Consumption and Expenditure – The Keynesian Cross The following table gives some information regarding GDP, Consumption (C), Taxes (T), Transfers (TR), and Investment (I) in the autarkic (no imports or exports) nation of Haagland. Year GDP or Y C T TR G I 2014 $350 $200 $100 $50 $75 $200 2015 $450 $250 $100 $50 $75 $200 a) Given the above information, assuming that autonomous consumption and the marginal propensity to consume are constant, find an equation for consumption as a function of disposable income (Disposable Income = Yd = Y – (T – TR)). The fact that autonomous consumption and MPC are constant tells us that the consumption function is linear; thus, we need only identify two points that lie on the consumption function line to solve for the line. -

Production Networks and the Flattening of the Phillips Curve∗

Production Networks and the Flattening of the Phillips Curve∗ Christian H¨oynck y Click here for latest version February 13, 2020 Abstract This paper analyzes the role of changes in the structure of production networks on the flattening of the Phillips curve over the last decades. I build a multi-sector model with production networks, and heterogeneity in input-output linkages and in degree of nominal rigidities. In the production network model, inflation sensitivity to the output gap depends on the topology of the network of the economy. In particular, I show that two characteristics of the network matter for inflation dynamics: (i) the network multiplier and (ii) output shares. Analyzing the U.S. Input-Output structure from 1963 to 2017, I document structural changes in the production network. Calibrating the model to these sectoral changes can account for a decrease in the slope of up to 15 percent. Decomposing the aggregate effect shows that the flattening is primarily due to an increase in the centrality of sectors with more rigid prices that is incompletely reflected by compositional changes in value-added. JEL codes: C67, E23, E31, E32, E52, E58 Key words: Production Networks, Inflation Dynamics, Phillips Curve, Sectoral Hetero- geneity, Nominal Rigidities, New-Keynesian Model ∗I am extremely grateful to my advisors Jordi Gal´ı,and, Barbara Rossi for invaluable guidance and support, and to Davide Debortoli and Edouard Schaal for comments that substantially improved this paper. I would also like to thank Regis Barnichon, Isaac Baley, Saki Bigio, Roberto Billi, Manuel Garc´ıa-Santana, Geert Mesters, Michael Weber, Lutz Weinke and seminar and conference participants at Vigo Workshop on Dynamic Macroeconomics, and CREi macro lunch for helpful comments on this and earlier drafts of the paper. -

Effective Demand Failures and the Limits of Monetary Stabilization Policy

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES EFFECTIVE DEMAND FAILURES AND THE LIMITS OF MONETARY STABILIZATION POLICY Michael Woodford Working Paper 27768 http://www.nber.org/papers/w27768 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2020, Revised September 2021 An earlier version was presented at the 2020 NBER Summer Institute under the title “Pandemic Shocks, Effective Demand, and Stabilization Policy.” I would like to thank Aloísio Araújo, Gauti Eggertsson, Guido Lorenzoni, Argia Sbordone, Ludwig Straub, Harald Uhlig, and Iván Werning for helpful comments, and Yeji Sung for research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2020 by Michael Woodford. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Effective Demand Failures and the Limits of Monetary Stabilization Policy Michael Woodford NBER Working Paper No. 27768 September 2020, Revised September 2021 JEL No. E12,E52,E63 ABSTRACT The challenge for stabilization policy presented by the COVID-19 pandemic stems above all from disruption of the circular flow of payments, resulting in a failure of what Keynes (1936) calls “effective demand.” As a consequence, economic activity in many sectors can be inefficiently low, and interest-rate policy cannot eliminate the distortions — not because of a limit on the extent to which interest rates can be reduced, but because interest-rate reductions fail to stimulate demand of the right sorts. -

Keynesian Cross Diagram (This Lecture Is Compiled from Internet)

Keynesian cross diagram (This lecture is compiled from internet) The fundamental ideas of Keynesian economics were developed before the AD/AS model was popularized. From the 1930s until the 1970s, Keynesian economics was usually explained with a different model, known as the expenditure-output approach. This approach is strongly rooted in the fundamental assumptions of Keynesian economics.It focuses on the total amount of spending in the economy, with no explicit mention of aggregate supply or of the price level . The Axes of the Expenditure-Output Diagram The expenditure-output model, sometimes also called the Keynesian cross diagram, determines the equilibrium level of real GDP by the point where the total or aggregate expenditures in the economy are equal to the amount of output produced. The axes of the Keynesian cross diagram presented in Figure below .It shows real GDP on the horizontal axis as a measure of output and aggregate expenditures on the vertical axis as a measure of spending. Figure = The Expenditure-Output Diagram The aggregate expenditure-output model shows aggregate expenditures on the vertical axis and real GDP on the horizontal axis. A vertical line shows potential GDP where full employment occurs. The 45-degree line shows all points where aggregate expenditures and output are equal. The aggregate expenditure schedule shows how total spending or aggregate expenditure increases as output or real GDP rises. The intersection of the aggregate expenditure schedule and the 45-degree line will be the equilibrium. Equilibrium occurs at E0, where aggregate expenditure AE0 is equal to the output level Y0. GDP can be thought of in several equivalent ways: it measures both the value of spending on final goods and also the value of the production of final goods. -

Lecture 21 4-12 Outline and Slides.Pdf

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2016 Professor David Romer LECTURE 21 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 12, 2016 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Evidence B. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) V. DETERMINANTS OF SHORT-RUN OUTPUT A. Equilibrium condition (Y=PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. Multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2016 David Romer LECTURE 21 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 12, 2016 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Tuesday, April 19th. • Problem set work session this Friday, April 15th, 4:30–6:30 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis Economic of Bureau Source: Real GDP (in logarithms) 10.0 7.5 8.0 8.5 9.0 9.5 Real GDP in the U.S. GDP since 1955 in the U.S. Real 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). -

The Keynesian Cross

✦ The Keynesian Cross Some instructors like to develop a more detailed macroeconomic model than is presented in the textbook. This supplemental material provides a concise description of the “Keynesian-cross model,” which underlies the aggregate-demand curve presented in the textbook. The Keynesian cross is based on the condition that the components of aggregate demand (consumption, invest- ment, government purchases, and net exports) must equal total output. In addition to developing the Keynesian cross in this section, we will also look at the behavior of the major sectors of the economy and develop a multiplier that will relate changes in any autonomous (independent of any changes in income) variable, including government spending and taxes, to changes in output. A Fixed Price Level In most of his supplement we will assume that the price level is fixed. If the price level is fixed, then changes in nominal income will be equivalent to changes in real income. That is, when assume the price level is fixed, we do not have to distinguish real variable changes from nominal variable changes. In the very short run, prices are fixed and sellers adjust output to meet the demand for goods and services. That is, the demand for output at a given price is determining how much each firm is producing and selling. The fixed price level assumption has an important implication: if demand determines the quantity of output that each firm sells, then it is aggregate demand that determines the level of real gross domestic product (RGDP) or the aggregate quantities of goods and services sold. -

Unemployment Insurance As an Economic Stabilizer: Evidence of Effectiveness Over Three Decades

Unemployment Insurance as an Economic Stabilizer: Evidence of Effectiveness Over Three Decades Unemployment Insurance Occasional Paper 99-8 U.S. Department of Labor Alexis M. Herman, Secretary Employment and Training Administration Raymond L. Bramucci, Assistant Secretary Unemployment Insurance Service Grace A. Kilbane, Director Division of Research and Policy Esther R. Johnson, Chief 1999 This report was prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Unemployment Insurance Service by Coffey Communications, LLC under contract number G-5914-6-00-87-30 (5). Its authors are Lawrence Chimerine, Theodore S. Black, and Lester Coffey. Since contractors conducting research and evaluation projects under government sponsorship are encouraged to express their own judgement freely, this report does not necessarily represent the official opinion or policy of the 4U.S. Department of Labor. The UIOP Series presents research findings and analyses dealing with unemployment insurance issues. Papers are prepared by research contractors, staff members of the unemployment insurance system, or individual researchers. Manuscripts and comments from interested individuals are welcome. All correspondence should be sent to: UI Occasional Papers Unemployment Insurance Service Frances Perkins Building, Room S-4231 200 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20210 email: [email protected] Unemployment Insurance as an Automatic Stabilizer: Evidence of Effectiveness Over Three Decades Lawrence Chimerine, Theodore S. Black, and Lester Coffey Coffey Communications, LLC Martha K. Matzke, Editor July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 10 I THE UI PROGRAM AND ECONOMIC STABILIZATION 11 II UI AS AN AUTOMATIC STABILIZER: DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS 16 III REVIEW OF RECENT LITERATURE 27 IV IS THE BUSINESS CYCLE OBSOLETE? 37 V EVIDENCE OF THE ABSOLUTE EFFECTIVENESS OF UI AS AN AUTOMATIC STABILIZER: A SIMULATION ANALYSIS 60 VI EVIDENCE OF THE RELATIVE EFFECTIVENESS OF UI AS AN AUTOMATIC STABILIZER FOR THE U.S. -

The Keynesian Theory of Determination of National Income

UNIT II: THE KEYNESIAN THEORY OF DETERMINATION OF NATIONAL INCOME LEARNING OUTCOMES At the end of this unit, you will be able to: Define Keynes’ concept of equilibrium aggregate income Describe the components of aggregate expenditure in two, three and four sector economy models Explain national income determination in two, three and four sector economy models Illustrate the functioning of multiplier, and Outline the changes in equilibrium aggregate income on account of changes in its determinants Determination of National Income The Keynesian Theory of Determination of National Income Determination of The Two-Sector Model The Determination of Equilibrium for National Income Investment Equilibrium Income : Income : Four Determination Multiplier Three Sector Model Sector Model © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India 1.36 ECONOMICS FOR FINANCE 2.1 INTRODUCTION In the last unit on measurement of national income, we have developed theoretical insights into the different concepts of national income and methods of measurement. In this unit, we shall focus on two issues namely, the factors that determine the level of national income and the determination of equilibrium aggregate income and output in an economy. A comprehensive theory to explain these phenomena was first put forward by the British economist John Maynard Keynes in his masterpiece ‘The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money’ published in 1936. The Keynesian theory of income determination is presented in three models: (i) The two-sector model consisting of the household and the business sectors, (ii) The three-sector model consisting of household, business and government sectors, and (iii) The four-sector model consisting of household, business, government and foreign sectors Before we attempt to explain the determination of income in each of the above models, it is pertinent that we understand the concept of circular flow in an economy which explains the functioning of an economy. -

Economic Fluctuations and Macroeconomic Theory

Chapter 9 ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS AND MACROECONOMIC THEORY Essentials of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 1st Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Understand economists’ notions of frictional, structural, and cyclical unemployment. 3. Describe the consequences of inflation and deflation. 4. Identify and distinguish the major historical traditions of economic thought. 5. Describe the key assumptions of classical theory and explain the classical theory of equilibrium in the goods and labor market. 6. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 7. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model. 8. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 9. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms aggregate demand structural unemployment recession technological unemployment Okun’s “law” full-employment cyclical unemployment deflation frictional unemployment full-employment output Chapter 9 – Economic Fluctuations and Macroeconomic Theory 1 classical economics marginal propensity to consume division of labor marginal propensity to save specialization Keynesian economics labor productivity paradox of thrift laissez-faire economy monetarism Say’s law Active Review Fill in the Blank 1.