Macroeconomics Exam Review Chapters 5 Through 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 17: Consumption 1

11/6/2013 Keynes’s conjectures Chapter 17: Consumption 1. 0 < MPC < 1 2. Average propensity to consume (APC) falls as income rises. (APC = C/Y ) 3. Income is the main determinant of consumption. CHAPTER 17 Consumption 0 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 1 The Keynesian consumption function The Keynesian consumption function As income rises, consumers save a bigger C C fraction of their income, so APC falls. CCcY CCcY c c = MPC = slope of the 1 CC consumption APC c C function YY slope = APC Y Y CHAPTER 17 Consumption 2 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 3 Early empirical successes: Problems for the Results from early studies Keynesian consumption function . Households with higher incomes: . Based on the Keynesian consumption function, . consume more, MPC > 0 economists predicted that C would grow more . save more, MPC < 1 slowly than Y over time. save a larger fraction of their income, . This prediction did not come true: APC as Y . As incomes grew, APC did not fall, . Very strong correlation between income and and C grew at the same rate as income. consumption: . Simon Kuznets showed that C/Y was income seemed to be the main very stable in long time series data. determinant of consumption CHAPTER 17 Consumption 4 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 5 1 11/6/2013 The Consumption Puzzle Irving Fisher and Intertemporal Choice . The basis for much subsequent work on Consumption function consumption. C from long time series data (constant APC ) . Assumes consumer is forward-looking and chooses consumption for the present and future to maximize lifetime satisfaction. Consumption function . Consumer’s choices are subject to an from cross-sectional intertemporal budget constraint, household data a measure of the total resources available for (falling APC ) present and future consumption. -

Shopping Enjoyment and Obsessive-Compulsive Buying

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/EJBM Vol.11, No.3, 2019 Young Buyers: Shopping Enjoyment and Obsessive-Compulsive Buying Ayaz Samo 1 Hamid Shaikh 2 Maqsood Bhutto 3 Fiza Rani 3 Fayaz Samo 2* Tahseen Bhutto 2 1.School of Business Administration, Shah Abdul Latif University, Khairpur, Sindh, Pakistan 2.School of Business Administration, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian, China 3.Sukkur Institute of Business Administration, Sindh, Pakistan Abstract The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the relationship between hedonic shopping motivations and obsessive- compulsive shopping behavior from youngsters’ perspective. The study is based on the survey of 615 young Chinese buyers (mean age=24) and analyzed through Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The findings show that adventure seeking, gratification seeking, and idea shopping have a positive effect on obsessive-compulsive buying, whereas role shopping and value shopping have a negative effect on obsessive-compulsive buying. However, social shopping is found to be insignificant to obsessive-compulsive buying. The study has a number of implications. Marketers should display more information about latest trends and fashions, as young buyers are found to shop for ideas and information. Managers should design the layouts with more exciting and impressive features, as these buyers are found to shop for adventure and gratification. Salesmen should take greater care into consideration while offering them to buy products such as gifts, souvenir etc. for their dear ones, as these buyers are less likely to enjoy buying for others. Moreover, business managers should less rely on discount promotions, as this consumer segment is found to be less likely to shop for discounts and bargains. -

What Role Does Consumer Sentiment Play in the U.S. Economy?

The economy is mired in recession. Consumer spending is weak, investment in plant and equipment is lethargic, and firms are hesitant to hire unemployed workers, given bleak forecasts of demand for final products. Monetary policy has lowered short-term interest rates and long rates have followed suit, but consumers and businesses resist borrowing. The condi- tions seem ripe for a recovery, but still the economy has not taken off as expected. What is the missing ingredient? Consumer confidence. Once the mood of consumers shifts toward the optimistic, shoppers will buy, firms will hire, and the engine of growth will rev up again. All eyes are on the widely publicized measures of consumer confidence (or consumer sentiment), waiting for the telltale uptick that will propel us into the longed-for expansion. Just as we appear to be headed for a "double-dipper," the mood swing occurs: the indexes of consumer confi- dence register 20-point increases, and the nation surges into a prolonged period of healthy growth. oes the U.S. economy really behave as this fictional account describes? Can a shift in sentiment drive the economy out of D recession and back into good health? Does a lack of consumer confidence drag the economy into recession? What causes large swings in consumer confidence? This article will try to answer these questions and to determine consumer confidence’s role in the workings of the U.S. economy. ]effre9 C. Fuhrer I. What Is Consumer Sentitnent? Senior Econotnist, Federal Reserve Consumer sentiment, or consumer confidence, is both an economic Bank of Boston. -

Untangling Misconceptions About Inflation and Predicting Its Path After COVID-19

GLOBAL EQUITY Investment Management active.williamblair.com Low-Inflation Nation: Untangling Misconceptions About Inflation and Predicting Its Path After COVID-19 Investors are preoccupied with inflation for good reason: It affects interest October 2020 rates, public-equity valuations, private-equity access to capital and, Global Strategist ultimately, stock-price multiples. Yet confusion about inflation assumptions Olga Bitel, Partner and forecasts could lead investors astray. In this report, Olga Bitel, partner, global strategist, discusses inflation and the factors that influence it. She explains why both aggregate demand growth and inflation may be higher over the next decade than in the 2010s, with major implications for asset allocation. Introduction Inflation is a subject that can spur extreme opinions, often without evidence to support them. Misconceptions about inflation abound, particularly as the European Central Bank (ECB), U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), and others have pursued unconventional monetary policies. Some investors have blamed central banks for slow economic growth between 2008 and 2019. Others predicted a surge in inflation that never materialized. D.J. Neiman, CFA, Investors are preoccupied with inflation for good reason: It affects interest rates, public- Partner equity valuations, private-equity access to capital and, ultimately, stock-price multiples. The recent policy change announced by U.S. Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell to allow inflation to run at an average rate of 2% over time, rather than setting that figure as a strict threshold, will fuel the debate about central-bank policy, inflation, and growth. Yet confusion about inflation assumptions and forecasts could lead investors astray. Olga Bitel, global strategist at William Blair, developed this report to clarify the definition of inflation and the factors that influence it. -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: National Saving and Economic Performance Volume Author/Editor: B. Douglas Bernheim and John B. Shoven, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-04404-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bern91-2 Conference Date: January 6-7, 1989 Publication Date: January 1991 Chapter Title: Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence Chapter Author: Christopher D. Carroll, Lawrence H. Summers Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5995 Chapter pages in book: (p. 305 - 348) 10 Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence Christopher D. Carroll and Lawrence H. Summers 10.1 Introduction The idea that consumers allocate their consumption over time so as to max- imize a stable individualistic utility function provides the basis for almost all modem work on the determinants of consumption and saving decisions. The celebrated life-cycle and permanent income hypotheses represent not so much alternative theories of consumption as alternative empirical strategies for fleshing out the same basic idea. While tests of particular implementations of these theories sometimes lead to statistical rejections, life-cycle/permanent income theories succeed in unifying a wide range of diverse phenomena. It is probably fair to accept Franc0 Modigliani’s ( 1980) characterization that “the Life Cycle Hypothesis has proved a very fruitful hypothesis, capable of inte- grating a large variety of facts concerning individual and aggregate saving behaviour.” This paper argues, however, that both permanent income and, to an only slightly lesser extent, life-cycle theories as they have come to be implemented in recent years are inconsistent with the grossest features of cross-country and cross-section data on consumption and income and income growth. -

Has the US Finance Industry Become Less Efficient? on the Theory and Measurement of Financial Intermediation†

American Economic Review 2015, 105(4): 1408–1438 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120578 Has the US Finance Industry Become Less Efficient? On the Theory and Measurement of Financial Intermediation† By Thomas Philippon * A quantitative investigation of financial intermediation in the United States over the past 130 years yields the following results: i the finance industry’s share of gross domestic product GDP is high( ) in the 1920s, low in the 1960s, and high again after 1980( ; )ii most of these variations can be explained by corresponding changes( ) in the quantity of intermediated assets equity, household and corporate debt, liquidity ; iii intermediation( has constant returns to scale and an annual cost) of( 1.5–2) percent of intermediated assets; iv secular changes in the characteristics of firms and households are( )quantita- tively important. JEL D24, E44, G21, G32, N22 ( ) This paper is concerned with the theory and measurement of financial interme- diation. The role of the finance industry is to produce, trade, and settle financial contracts that can be used to pool funds, share risks, transfer resources, produce information, and provide incentives. Financial intermediaries are compensated for providing these services. The income received by these intermediaries measures the aggregate cost of financial intermediation. This income is the sum of all spreads and fees paid by nonfinancial agents to financial intermediaries and it is also the sum of all profits and wages in the finance industry. This cost of financial intermediation affects the user cost of external finance for firms who issue debt and equity, and the costs for households who borrow or use asset management services. -

The Time Series Consumption Function Revisited

ALAN S. BLINDER Brookings Institution and Princeton University ANGUS DEATON Princeton University The Time Series Consumption Function Revisited THERELATIONSHIP between consumer spending and income is one of the oldest statistical regularitiesof macroeconomics-and one of the stur- diest. Like the aging movie star, it needs a little touching up now and again, but always seems to come bouncingback. A dozen yearsago, boththe theoreticalderivation and the econometric form of the aggregateconsumption function were considered settled. Most economists adheredto one of two ways of puttingFisher's theory of intertemporaloptimization into operation: Milton Friedman's per- manent income hypothesis (henceforth, PIH) or Franco Modigliani's life-cycle hypothesis (henceforth,LCH). ' Since each variantseemed to have sound theoretical underpinnings,and since the two had similar econometricforms that explainedthe data well and had similarimplica- tions for policy, there was not a greatdeal to quarrelabout. Perhapsthe most contentious empirical issue was the apparently large marginal This paperhas benefitedfrom the commentsand suggestionsof AlbertAndo, Whitney Newey, and members of the Brookings Panel and from seminar presentationsat the Universityof Warwick,Princeton University, and Johns Hopkins University.We thank Peter Rathjensand Lori Gruninfor researchassistance and the National Science Foun- dationfor financialsupport. 1. Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function (Princeton University Press, 1957); Franco Modigliani and Richard Brumberg, -

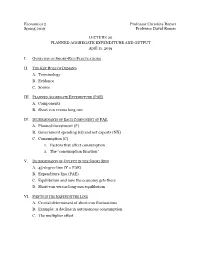

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

GDP As a Measure of Economic Well-Being

Hutchins Center Working Paper #43 August 2018 GDP as a Measure of Economic Well-being Karen Dynan Harvard University Peterson Institute for International Economics Louise Sheiner Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution The authors thank Katharine Abraham, Ana Aizcorbe, Martin Baily, Barry Bosworth, David Byrne, Richard Cooper, Carol Corrado, Diane Coyle, Abe Dunn, Marty Feldstein, Martin Fleming, Ted Gayer, Greg Ip, Billy Jack, Ben Jones, Chad Jones, Dale Jorgenson, Greg Mankiw, Dylan Rassier, Marshall Reinsdorf, Matthew Shapiro, Dan Sichel, Jim Stock, Hal Varian, David Wessel, Cliff Winston, and participants at the Hutchins Center authors’ conference for helpful comments and discussion. They are grateful to Sage Belz, Michael Ng, and Finn Schuele for excellent research assistance. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. Neither is currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. ________________________________________________________________________ THIS PAPER IS ONLINE AT https://www.brookings.edu/research/gdp-as-a- measure-of-economic-well-being ABSTRACT The sense that recent technological advances have yielded considerable benefits for everyday life, as well as disappointment over measured productivity and output growth in recent years, have spurred widespread concerns about whether our statistical systems are capturing these improvements (see, for example, Feldstein, 2017). While concerns about measurement are not at all new to the statistical community, more people are now entering the discussion and more economists are looking to do research that can help support the statistical agencies. While this new attention is welcome, economists and others who engage in this conversation do not always start on the same page. -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics