Production Networks and the Flattening of the Phillips Curve∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment

Conference Series No. 19 BAILY BOSWORTH FAIR FRIEDMAN HELLIWELL KLEIN LUCAS-SARGENT MC NEES MODIGLIANI MOORE MORRIS POOLE SOLOW WACHTER-WACHTER % FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON AFTER THE PHILLIPS CURVE: PERSISTENCE OF HIGH INFLATION AND HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT Proceedings of a Conference Held at Edgartown, Massachusetts June 1978 Sponsored by THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON CONFERENCE SERIES NO. 1 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES JUNE, 1969 NO. 2 THE INTERNATIONAL ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM OCTOBER, 1969 NO. 3 FINANCING STATE and LOCAL GOVERNMENTS in the SEVENTIES JUNE, 1970 NO. 4 HOUSING and MONETARY POLICY OCTOBER, 1970 NO. 5 CONSUMER SPENDING and MONETARY POLICY: THE LINKAGES JUNE, 1971 NO. 6 CANADIAN-UNITED STATES FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS SEPTEMBER, 1971 NO. 7 FINANCING PUBLIC SCHOOLS JANUARY, 1972 NO. 8 POLICIES for a MORE COMPETITIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEM JUNE, 1972 NO. 9 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES II: the IMPLEMENTATION SEPTEMBER, 1972 NO. 10 ISSUES .in FEDERAL DEBT MANAGEMENT JUNE 1973 NO. 11 CREDIT ALLOCATION TECHNIQUES and MONETARY POLICY SEPBEMBER 1973 NO. 12 INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS of STABILIZATION POLICIES JUNE 1974 NO. 13 THE ECONOMICS of a NATIONAL ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SYSTEM OCTOBER 1974 NO. 14 NEW MORTGAGE DESIGNS for an INFLATIONARY ENVIRONMENT JANUARY 1975 NO. 15 NEW ENGLAND and the ENERGY CRISIS OCTOBER 1975 NO. 16 FUNDING PENSIONS: ISSUES and IMPLICATIONS for FINANCIAL MARKETS OCTOBER 1976 NO. 17 MINORITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 18 KEY ISSUES in INTERNATIONAL BANKING OCTOBER, 1977 CONTENTS Opening Remarks FRANK E. MORRIS 7 I. Documenting the Problem 9 Diagnosing the Problem of Inflation and Unemployment in the Western World GEOFFREY H. -

Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve Mary C. Daly Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Bart Hobijn Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, VU University Amsterdam and Tinbergen Institute January 2014 Working Paper 2013-08 http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2013/wp2013-08.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve MARY C. DALY BART HOBIJN 1 FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO VU UNIVERSITY AMSTERDAM, AND TINBERGEN INSTITUTE January 11, 2014. We introduce a model of monetary policy with downward nominal wage rigidities and show that both the slope and curvature of the Phillips curve depend on the level of inflation and the extent of downward nominal wage rigidities. This is true for the both the long-run and the short-run Phillips curve. Comparing simulation results from the model with data on U.S. wage patterns, we show that downward nominal wage rigidities likely have played a role in shaping the dynamics of unemployment and wage growth during the last three recessions and subsequent recoveries. Keywords: Downward nominal wage rigidities, monetary policy, Phillips curve. JEL-codes: E52, E24, J3. 1 We are grateful to Mike Elsby, Sylvain Leduc, Zheng Liu, and Glenn Rudebusch, as well as seminar participants at EIEF, the London School of Economics, Norges Bank, UC Santa Cruz, and the University of Edinburgh for their suggestions and comments. -

Karl Marx's Thoughts on Functional Income Distribution - a Critical Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Herr, Hansjörg Working Paper Karl Marx's thoughts on functional income distribution - a critical analysis Working Paper, No. 101/2018 Provided in Cooperation with: Berlin Institute for International Political Economy (IPE) Suggested Citation: Herr, Hansjörg (2018) : Karl Marx's thoughts on functional income distribution - a critical analysis, Working Paper, No. 101/2018, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/175885 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Institute for International Political Economy Berlin Karl Marx’s thoughts on functional income distribution – a critical analysis Author: Hansjörg Herr Working Paper, No. -

The Return of the Wage Phillips Curve

THE RETURN OF THE WAGE PHILLIPS CURVE Jordi Gal´ı CREI, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Barcelona GSE Abstract The standard New Keynesian model with staggered wage setting is shown to imply a simple dynamic relation between wage inflation and unemployment. Under some assumptions, that relation takes a form similar to that found in empirical wage equations—starting from Phillips’ (1958) original work—and may thus be viewed as providing some theoretical foundations to the latter. The structural wage equation derived here is shown to account reasonably well for the comovement of wage inflation and the unemployment rate in the US economy, even under the strong assumption of a constant natural rate of unemployment. (JEL: E24, E31, E32) 1. Introduction The past decade has witnessed the emergence of a new popular framework for monetary policy analysis, the so-called New Keynesian (NK) model. The new framework combines some of the ingredients of Real Business Cycle theory (for example dynamic optimization, general equilibrium) with others that have a distinctive Keynesian flavor (for example monopolistic competition, nominal rigidities). Many important properties of the NK model hinge on the specification of its wage- setting block. While basic versions of that model, intended for classroom exposition, assume fully flexible wages and perfect competition in labor markets, the larger, more realistic versions (including those developed in-house at different central banks and policy institutions) typically assume staggered nominal wage setting which, following the lead of Erceg, Henderson, and Levin (2000), are modeled in a way symmetric to The editor in charge of this paper was Fabrizio Zilibotti. -

Recovering Keynesian Phillips Curve Theory: Hysteresis of Ideas and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Palley, Thomas Working Paper Recovering Keynesian Phillips Curve Theory: Hysteresis of Ideas and the Natural Rate of Unemployment FMM Working Paper, No. 26 Provided in Cooperation with: Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at the Hans Boeckler Foundation Suggested Citation: Palley, Thomas (2018) : Recovering Keynesian Phillips Curve Theory: Hysteresis of Ideas and the Natural Rate of Unemployment, FMM Working Paper, No. 26, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK), Forum for Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (FFM), Düsseldorf This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/181484 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu FMM WORKING PAPER No. 26 · June, 2018 · Hans-Böckler-Stiftung RECOVERING KEYNESIAN PHILLIPS CURVE THEORY: HYSTERESIS OF IDEAS AND THE NATURAL RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT Thomas Palley* ABSTRACT Economic theory is prone to hysteresis. -

The Phillips Curve and U.S. Macroeconomic Policy: Snapshots, 1958-1996

Economic Quarterly—Volume 94, Number 4—Fall 2008—Pages 311–359 The Phillips Curve and U.S. Macroeconomic Policy: Snapshots, 1958–1996 Robert G. King he curve first drawn by A.W. Phillips in 1958, highlighting a negative relationship between wage inflation and unemployment, figured T prominently in the theory and practice of macroeconomic policy during 1958–1996. Within a decade of Phillips’ analysis, the idea of a relatively stable long- run tradeoff between price inflation and unemployment was firmly built into policy analysis in the United States and other countries. Such a long-run tradeoff was at the core of most prominent macroeconometric models as of 1969. Over the ensuing decade, the United States and other countries experi- enced stagflation, a simultaneous rise of unemployment and inflation, which threw the consensus about the long-run Phillips curve into disarray. By the end of the 1970s, inflation was historically high—near 10 percent—and poised to rise further. Economists and policymakers stressed the role of shifting ex- pectations of inflation and differed widely on the costliness of reducing infla- tion, in part based on alternative views of the manner in which expectations were formed. In the early 1980s, the Federal Reserve System undertook an unwinding of inflation, producing a multiyear interval in which inflation fell substantially and permanently while unemployment rose substantially but temporarily. Although costly, the disinflation process involved lower unem- ployment losses than predicted by consensus macroeconomists, as rational expectations analysts had suggested that it would. The author is affiliated with Boston University, National Bureau of Economic Research, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. -

The Labor Market and the Phillips Curve

4 The Labor Market and the Phillips Curve A New Method for Estimating Time Variation in the NAIRU William T. Dickens The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is fre- quently employed in fiscal and monetary policy deliberations. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office uses estimates of the NAIRU to compute potential GDP, that in turn is used to make budget projections that affect decisions about federal spending and taxation. Central banks consider estimates of the NAIRU to determine the likely course of inflation and what actions they should take to preserve price stability. A problem with the use of the NAIRU in policy formation is that it is thought to change over time (Ball and Mankiw 2002; Cohen, Dickens, and Posen 2001; Stock 2001; Gordon 1997, 1998). But estimates of the NAIRU and its time variation are remarkably imprecise and are far from robust (Staiger, Stock, and Watson 1997, 2001; Stock 2001). NAIRU estimates are obtained from estimates of the Phillips curve— the relationship between the inflation rate, on the one hand, and the unemployment rate, measures of inflationary expectations, and variables representing supply shocks on the other. Typically, inflationary expecta- tions are proxied with several lags of inflation and the unemployment rate is entered with lags as well. The NAIRU is recovered as the constant in the regression divided by the coefficient on unemployment (or the sum of the coefficient on unemployment and its lags). The notion that the NAIRU might vary over time goes back at least to Perry (1970), who suggested that changes in the demographic com- position of the labor force would change the NAIRU. -

The Phillips Curve Evaluating Short-Run Inflation/Unemployment Dynamics

The Phillips Curve Evaluating Short-Run Inflation/Unemployment Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. Inflation-Unemployment Trade-Off 2. Phillips Curve 3. Zero Bound for Inflation • Textbook Readings: Ch. 17 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Discovery of Short-Run Trade-Off between � and U • Phillips curve: A curve showing the short-run inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate • Named after economist A. W. Phillips (1958) Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Is The Phillips Curve A Policy Menu? • During the 1960s, some economists argued that the Phillips curve was a structural relationship: § A relationship that depends on the basic behavior of consumers and firms, and that remains unchanged over a long period • If this was true, policy-makers could choose a point on the curve Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University AD/AS Model Helps Us Derive the Phillips Curve • Recall: § The short-run macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when the AD and SRAS curves intersect § The long-run macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when the AD and SRAS curves intersect at the LRAS Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Short-Run Equilibrium Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Long-Run Equilibrium Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Short-Run vs Long-Run Equilibrium • We began in long run equilibrium: AD = SRAS = LRAS • G increased, increasing AD: AD = SRAS ≠ LRAS • This drives prices up, wage earners -

What's up with the Phillips Curve?

BPEA Conference Drafts, March 19, 2020 What’s Up with the Phillips Curve? Marco Del Negro, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Michele Lenza, European Central Bank Giorgio E. Primiceri, Northwestern University Andrea Tambalotti, Federal Reserve Bank of New York DO NOT DISTRIBUTE – ALL PAPERS ARE EMBARGOED UNTIL 9:01PM ET 3/18/2020 Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Marco Del Negro is Vice President in the Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies Function of the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Michele Lenza is Head of Section for the Monetary Policy Research Division of the European Central Bank, the Forecasting and Business Cycle group leader and research coordinator for the European Central Bank, and a member of the Forecast Steering Committee for the European Central Bank; Giorgio Primiceri is a professor of economics at Northwestern University and co-editor of the American Economics Journal; Andrea Tambalotti is Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Beyond these affiliations, the authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of Northwestern University, the American Economics Journal, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or the European Central Bank. WHAT’S UP WITH THE PHILLIPS CURVE? MARCO DEL NEGRO, MICHELE LENZA, GIORGIO E. PRIMICERI, AND ANDREA TAMBALOTTI Abstract. The business cycle is alive and well, and real variables respond to it more or less as they always did. -

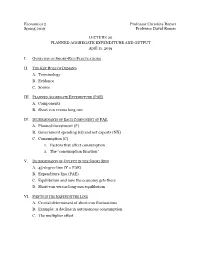

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

Keynes's Employment Function and the Gratuitous Phillips Curve Disaster

Working Paper No. 773 Keynes’s Employment Function and the Gratuitous Phillips Curve Disaster by Egmont Kakarot-Handtke* Institute of Economics and Law, University of Stuttgart August 2013 * Correspondence: AXEC-Project, Egmont Kakarot-Handtke, Hohenzollernstraße 11, D-80801 München, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2013 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT Keynes had many plausible things to say about unemployment and its causes. His “mercurial mind,” though, relied on intuition, which means that he could not strictly prove his hypotheses. This explains why Keynes’s ideas immediately invited bastardizations. One of them, the Phillips curve synthesis, turned out to be fatal. This paper identifies Keynes’s undifferentiated employment function as a sore spot. It is replaced by the structural employment -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of .