The Labor Market and the Phillips Curve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

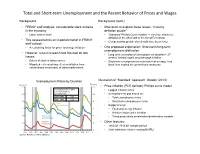

Total and Short-Term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages

Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Background Background (cont.) • FRBNY staff analysis: considerable slack remains • Motivation to explore these issues: “missing in the economy deflation puzzle” • Labor market flows • “Standard” Phillips Curve models → very low inflation or deflation in the aftermath of the Great Recession • This assessment is an important factor in FRBNY • Compensation growth also should have been lower staff outlook • A restraining factor for price- and wage-inflation • One proposed explanation: Short-term/long-term unemployment distinction • However, recent research has focused on two • Long-term unemployed (unemployment duration > 27 issues: weeks): limited impact on price/wage inflation • Extent of slack in labor market • Short-term unemployment near historical average: less • Magnitude of restraining effect on inflation from slack than implied by conventional measures conventional measure(s) of labor market slack Unemployment Rates by Duration Illustration of “Standard” Approach: Gordon (2013) Percent Percent 12 12 • Price-inflation (PCE deflator) Phillips curve model: Correlation Between Short- • Lagged inflation terms term and Long-term 10 Unemployment 10 • Unemployment gap based on: 1976—2007 0.63 • Total unemployment rate 1976—2013 0.28 8 8 • Short-term unemployment rate Total Unemployment • Supply shocks: 6 6 • Food and energy inflation • Relative import price inflation 4 Short-term 4 • Trend productivity acceleration/deceleration variable Unemployment Long-term • Other features: 2 Unemployment 2 • 1960:Q1-2013:Q1 sample period 0 0 • Joint estimation of time-varying NAIRU 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 4 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Total and Short-term Unemployment and the Recent Behavior of Prices and Wages Evaluation of Short-term vs. -

Is Unemployment Structural Or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU After the Crisis

IZA Policy Paper No. 91 Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis Alfonso Arpaia Aron Kiss Alessandro Turrini P O L I C Y P A P E R S I E S P A P Y I C O L P September 2014 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis Alfonso Arpaia European Commission, DG ECFIN and IZA Aron Kiss European Commission, DG ECFIN Alessandro Turrini European Commission, DG ECFIN and IZA Policy Paper No. 91 September 2014 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] The IZA Policy Paper Series publishes work by IZA staff and network members with immediate relevance for policymakers. Any opinions and views on policy expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of IZA. The papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the corresponding author. IZA Policy Paper No. 91 September 2014 ABSTRACT Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? * Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis The paper sheds light on developments in labour market matching in the EU after the crisis. First, it analyses the main features of the Beveridge curve and frictional unemployment in EU countries, with a view to isolate temporary changes in the vacancy-unemployment relationship from structural shifts affecting the efficiency of labour market matching. -

After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment

Conference Series No. 19 BAILY BOSWORTH FAIR FRIEDMAN HELLIWELL KLEIN LUCAS-SARGENT MC NEES MODIGLIANI MOORE MORRIS POOLE SOLOW WACHTER-WACHTER % FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON AFTER THE PHILLIPS CURVE: PERSISTENCE OF HIGH INFLATION AND HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT Proceedings of a Conference Held at Edgartown, Massachusetts June 1978 Sponsored by THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON CONFERENCE SERIES NO. 1 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES JUNE, 1969 NO. 2 THE INTERNATIONAL ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM OCTOBER, 1969 NO. 3 FINANCING STATE and LOCAL GOVERNMENTS in the SEVENTIES JUNE, 1970 NO. 4 HOUSING and MONETARY POLICY OCTOBER, 1970 NO. 5 CONSUMER SPENDING and MONETARY POLICY: THE LINKAGES JUNE, 1971 NO. 6 CANADIAN-UNITED STATES FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS SEPTEMBER, 1971 NO. 7 FINANCING PUBLIC SCHOOLS JANUARY, 1972 NO. 8 POLICIES for a MORE COMPETITIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEM JUNE, 1972 NO. 9 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES II: the IMPLEMENTATION SEPTEMBER, 1972 NO. 10 ISSUES .in FEDERAL DEBT MANAGEMENT JUNE 1973 NO. 11 CREDIT ALLOCATION TECHNIQUES and MONETARY POLICY SEPBEMBER 1973 NO. 12 INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS of STABILIZATION POLICIES JUNE 1974 NO. 13 THE ECONOMICS of a NATIONAL ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SYSTEM OCTOBER 1974 NO. 14 NEW MORTGAGE DESIGNS for an INFLATIONARY ENVIRONMENT JANUARY 1975 NO. 15 NEW ENGLAND and the ENERGY CRISIS OCTOBER 1975 NO. 16 FUNDING PENSIONS: ISSUES and IMPLICATIONS for FINANCIAL MARKETS OCTOBER 1976 NO. 17 MINORITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 18 KEY ISSUES in INTERNATIONAL BANKING OCTOBER, 1977 CONTENTS Opening Remarks FRANK E. MORRIS 7 I. Documenting the Problem 9 Diagnosing the Problem of Inflation and Unemployment in the Western World GEOFFREY H. -

Neoliberal Austerity and Unemployment

E L C I ‘…following Stuckler and Basu (2013) T it is not economic downturns per se that R matter but the austerity and welfare A “reform” that may follow: that “austerity Neoliberal austerity kills” and – as I argue here – that it particularly “kills” those in lower socio- economic positions.’ and unemployment The scale of contemporary unemployment consequent upon David Fryer and Rose Stambe examine critical psychological issues neoliberal austerity programmes is colossal. According to labour market statistics released in June 2013 by the UK Neoliberal fiscal austerity policies I am really sorry to bother you again. Office for National Statistics, 2.51 million decrease public expenditure God. But I am bursting to tell you all people were unemployed in the UK through cuts to central and local the stuff that has been going on (tinyurl.com/neu9l47). This represents five government budgets, welfare behind your back since I first wrote to unemployed people competing for every services and benefits and you back in 1988. Oh God do you still vacancy. privatisation of public resources remember? Remember me telling Official statistics like these, which have resulting in job losses. This article you of the war that was going on persisted now for years, do not, of course, interrogates the empirical, against the poor and unemployed in prevent the British Prime Minister – theoretical, methodological and our working class communities? Do evangelist of neoliberal government - ideological relationships between you remember me telling you, God, asking in a speech delivered in June 2012 neoliberalism, unemployment and how the people in my community ‘Why has it become acceptable for many the discipline of psychology, were being killed and terrorised but people to choose a life on benefits?’ arguing that neoliberalism that there were no soldiers to be Talking of what he termed ‘Working Age constitutes rather than causes seen, no tanks, no bombs being Welfare’, Mr Cameron opined: ‘we have unemployment. -

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗ Claude d'Aspremont,y Rodolphe Dos Santos Ferreiraz and Louis-Andr´eG´erard-Varetx 1 Introduction Attempts to explain unemployment1 begin with the labour market. Yet, by attributing it to deficient demand for goods, Keynes questioned the use of partial analysis, and stressed the need to consider interactions between the labour and product markets. Imperfect competition in the labour market, reflecting union power, has been a favoured explanation; but imperfect competition may also affect employment through producers' oligopolistic behaviour. This again points to a general equilibrium approach such as that by Negishi (1961, 1979). Here we propose an extension of the Cournot oligopoly model (unlike that of Gabszewicz and Vial (1972), where labour does not appear), which takes full account of the interdependence between the labour market and any product market. Our extension shares some features with both Negishi's conjectural approach to demand curves, and macroeconomic non-Walrasian equi- ∗Reprinted from Oxford Economic Papers, 41, 490-505, 1989. We thank P. Champsaur, P. Dehez, J.H. Dr`ezeand J.-J. Laffont for helpful comments. We owe P. Dehez the idea of a light strengthening of the results on involuntary unemployment given in a related paper (CORE D.P. 8408): see Dehez (1985), where the case of monopoly is studied. Acknowledgements are also due to Peter Sinclair and the Referees for valuable suggestions. This work is part of the program \Micro-d´ecisionset politique ´economique"of Commissariat G´en´eral au Plan. Financial support of Commissariat G´en´eralau Plan is gratefully acknowledged. -

New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically Tested in the Case of Republic of Macedonia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko Preprint New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia Suggested Citation: Josheski, Dushko; Lazarov, Darko (2012) : New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Empirically tested in the case of Republic of Macedonia, ZBW - Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft, Kiel und Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/64403 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu NEW KEYNESIAN MACROECONOMICS: EMPIRICALLY TESTED IN THE CASE OF REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Dushko Josheski 1 Darko Lazarov2 Abstract In this paper we test New Keynesian propositions about inflation and unemployment trade off with the New Keynesian Phillips curve and the proposition of non-neutrality of money. -

Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism

DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM RESEARCH AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DIVISION DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR MIKE MC CARTNEY DIRECTOR DR. EUGENE TIAN CHIEF STATE ECONOMIST FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 19, 2021 HAWAI‘I'S UNEMPLOYMENT RATE AT 7.3 PERCENT IN JULY Jobs increased by 53,000 over-the-year HONOLULU — The Hawai‘i State Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism (DBEDT) today announced that the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for July was 7.3 percent compared to 7.7 percent in June. Statewide, 598,850 were employed and 47,200 unemployed in July for a total seasonally adjusted labor force of 646,000. Nationally, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.4 percent in July, down from 5.9 percent in June. Seasonally Adjusted Unemployment Rate State of Hawai`i Jul 2019 - Jul 2021 28.0% 24.0% 20.0% 16.0% 12.0% 8.0% 4.0% 0.0% Ma Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Ma Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul y 19 19 19 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 y20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 Percent 2.5 2.4 2.3 2.2 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.1 2.1 21. 21. 14. 14. 14. 14. 14. 10. 10. 10. 9.2 9.1 8.5 8.0 7.7 7.3 The unemployment rate figures for the State of Hawai‘i and the U.S. in this release are seasonally adjusted, in accordance with the U.S. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB). -

Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve Mary C. Daly Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Bart Hobijn Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, VU University Amsterdam and Tinbergen Institute January 2014 Working Paper 2013-08 http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2013/wp2013-08.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve MARY C. DALY BART HOBIJN 1 FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO VU UNIVERSITY AMSTERDAM, AND TINBERGEN INSTITUTE January 11, 2014. We introduce a model of monetary policy with downward nominal wage rigidities and show that both the slope and curvature of the Phillips curve depend on the level of inflation and the extent of downward nominal wage rigidities. This is true for the both the long-run and the short-run Phillips curve. Comparing simulation results from the model with data on U.S. wage patterns, we show that downward nominal wage rigidities likely have played a role in shaping the dynamics of unemployment and wage growth during the last three recessions and subsequent recoveries. Keywords: Downward nominal wage rigidities, monetary policy, Phillips curve. JEL-codes: E52, E24, J3. 1 We are grateful to Mike Elsby, Sylvain Leduc, Zheng Liu, and Glenn Rudebusch, as well as seminar participants at EIEF, the London School of Economics, Norges Bank, UC Santa Cruz, and the University of Edinburgh for their suggestions and comments. -

Modern Monetary Theory: a Marxist Critique

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 2019 Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Michael Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Michael (2019) "Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008316 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/1 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Abstract Compiled from a series of blog posts which can be found at "The Next Recession." Modern monetary theory (MMT) has become flavor of the time among many leftist economic views in recent years. MMT has some traction in the left as it appears to offer theoretical support for policies of fiscal spending funded yb central bank money and running up budget deficits and public debt without earf of crises – and thus backing policies of government spending on infrastructure projects, job creation and industry in direct contrast to neoliberal mainstream policies of austerity and minimal government intervention. Here I will offer my view on the worth of MMT and its policy implications for the labor movement. First, I’ll try and give broad outline to bring out the similarities and difference with Marx’s monetary theory. -

Karl Marx's Thoughts on Functional Income Distribution - a Critical Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Herr, Hansjörg Working Paper Karl Marx's thoughts on functional income distribution - a critical analysis Working Paper, No. 101/2018 Provided in Cooperation with: Berlin Institute for International Political Economy (IPE) Suggested Citation: Herr, Hansjörg (2018) : Karl Marx's thoughts on functional income distribution - a critical analysis, Working Paper, No. 101/2018, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/175885 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Institute for International Political Economy Berlin Karl Marx’s thoughts on functional income distribution – a critical analysis Author: Hansjörg Herr Working Paper, No. -

What's Going on Behind the Euro Area Beveridge Curve(S)?

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO 1586 / SEPTEMBER 2013 What’S GOING ON BEHIND THE EURO AREA BEVERIDGE CURVE(S)? Boele Bonthuis, Valerie Jarvis and Juuso Vanhala 2012 STRUCTURAL ISSUES REPORT In 2013 all ECB publications feature a motif taken from the €5 banknote. NOTE: This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB. 2012 Structural Issues Report “Euro area labour markets and the crisis’’ This paper contains research underlying the 2012 Structural Issues Report “Euro area labour markets and the crisis’’, which was prepared by a Task Force of the Monetary Policy Committee of the European System of Central Banks. The Task Force was chaired by Robert Anderton (ECB). Mario Izquierdo (Banco de España) acted as Secretary. The Task Force consisted of experts from the ECB as well as the National Central Banks of the euro area countries. The main objectives of the Report was to shed light on developments in euro area labour markets during the crisis, including the notable heterogeneity across the euro area countries, as well as the medium- term consequences of these developments, along with the policy implications. The refereeing process of this paper has been co-ordinated by the Chairman and Secretary of the Task Force. Acknowledgements This paper was the result of background research for the Structural Issues Report 2012 “Euro area labour markets and the crisis”. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ECB, the Bank of Finland or the Eurosystem.